Real Women Have Curves

Real Women Have Curves is a 2002 American comedy-drama film directed by Patricia Cardoso, based on the play of the same name by Josefina López, who co-authored the screenplay for the film with George LaVoo. The film stars America Ferrera (in her feature film debut) as protagonist Ana García. It gained fame after winning the Audience Award for best dramatic film, and the Special Jury Prize for acting in the 2002 Sundance Film Festival. The film went on to receive the Youth Jury Award at the San Sebastian International Film Festival, the Humanitas Prize, the Imagen Award at the Imagen Foundation Awards, and Special Recognition by the National Board of Review. According to the Sundance Institute, the film gives a voice to young women who are struggling to love themselves and find respect in the United States.

| Real Women Have Curves | |

|---|---|

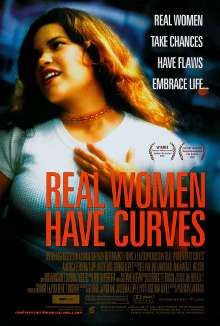

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Patricia Cardoso |

| Produced by |

|

| Screenplay by | |

| Based on | Real Women Have Curves by Josefina López |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Heitor Pereira |

| Cinematography | Jim Denault |

| Edited by | Sloane Klevin |

Production company |

|

| Distributed by | Newmarket Films |

Release date |

|

Running time | 93 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language |

|

| Box office | $7.7 million (worldwide)[1] |

In 2019, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[2]

Real Women Have Curves broke many conventions of traditional Hollywood film-making and became a landmark in American independent film. According to Entertainment Weekly, it is "one of the most influential movies of the 2000s," and cast "a wide shadow over the new generation of filmmakers to come." The movie is cited for showing "the impact a movie could have in the culture," and it is acclaimed for its nuanced portrayal of Los Angeles.

Plot

In East Los Angeles, California, 18-year-old Ana García, a student at a high school in Beverly Hills, struggles to balance her dream of going to college with family duty and a tough economic situation. While Ana's sister Estela and their father Raúl approve of her ambitions, Ana's mother Carmen resists the idea in favor of Ana helping Estela oversee the small, rundown family-owned textile factory, out of her desire to keep her family together and resolve their precarious finances.

On her last day of school, Ana's teacher, Mr. Guzman, asks her to consider applying to colleges. Ana explains that her family won't be able to afford it, and remarks that "it's too late anyway". Mr. Guzman disagrees and tells her that he knows the dean of admissions at Columbia University and could possibly have her application looked at, even if it is past the deadline. Ana tells him she will think about it.

That night, Ana's family throws her a party to celebrate her graduation. As the night continues, however, Carmen nags Ana about not eating too much cake because of her weight, and emphasizes the need for Ana to get married and have children. Ana's grandfather and father try to defuse the situation, until Carmen begins to discuss the family factory and suggest Ana start work there. Estela protests, saying there isn't enough to pay Ana, but fails to sway Carmen. Ana interjects that she wants to do something else, but her other job opportunities are limited. At that moment, her high school teacher arrives at the house, and asks to talk to Ana's parents about the possibilities of Ana going to college. Ana's mother is resolute, while Raúl seems open to the idea and assures Ana's teacher that he will think about it, after he initially hesitates to say anything in order to spare Carmen's feelings. Ana reluctantly agrees to work at the factory in the meantime.

After some time, Ana tries to get Estela to convince the executive in charge of her clothing line to grant her an advance so she can keep the factory running. When the executive refuses, Ana convinces her father to give Estela a small loan after seeing how hard Estela works to produce clothing she is proud of. Meanwhile, Ana works with Mr. Guzman at night to produce an essay for her application to Columbia in New York, which she successfully submits, while also developing a secret relationship with Jimmy, a cynical white fellow graduate. Carmen confronts Ana about her sexual activities. Ana insists that she as a person is more than what is between her legs, and begins to call her mother out on her emotionally abusive tendencies.

Later, at the factory, all of the women working there except Carmen grow exhausted of the heat and Carmen's critiques of their bodies and strip down to their underwear, comparing body shapes, stretch marks, and cellulite, inspiring confidence in one another's bodies. Carmen leaves the factory in a huff over her family and co-workers' lack of shame as Ana declares that they are women and this is who they are.

Near the end of summer, Mr. Guzman comes by the house to inform Ana and her family that Ana has been accepted to Columbia with a scholarship opportunity, though it would mean moving across the country from Los Angeles to New York City. At first, Carmen convinces Ana and the rest of the family that her place is in East Los Angeles, but eventually Ana decides that, having fully ensured Raúl's support, she needs to break free from her domineering mother. At the end of the film, Ana is dropped off at the airport by her father and grandfather while Carmen refuses to leave her room and say goodbye to Ana. The final scenes show Ana striding confidently through the streets of New York.

Cast

- America Ferrera as Ana García

- Lupe Ontiveros as Carmen García

- Jorge Cervera Jr. as Raúl García

- Ingrid Oliu as Estela García

- George Lopez as Mr. Guzman

- Brian Sites as Jimmy

- Soledad St. Hilaire as Pancha

- Lourdes Pérez as Rosali

- Josefina Lopez as Veronica

- José Gerardo Zamora Jr. as Juan José

- Manuel Edgar Luján as Juan Martin

- Erica Moller as Glitz Secretary

Reception

Critical

Real Women Have Curves received positive reviews for its theme (a positive body image), its realistic portrayal of a Mexican-American family and its acting. The film received an 84% "fresh" rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 85 reviews, with an average rating of 6.84/10. The site's consensus reads, "Even though Real Women is another coming-of-age tale, it's a real charmer."[3] On Metacritic, the film holds a score of 71/100 based on 28 reviews, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[4]

Elivis Mitchell of The New York Times described Real Women Have Curves as a "culture clash comic melodrama" that is, "effervescent and satisfying, a crowd pleaser that does not condescend."[5] Jean Oppenheimer of The Dallas Observer wrote "One of the strengths of Real Women Have Curves is that it isn't about just one thing; it is about many things. A coming-of-age drama centered on a mother-daughter conflict, it also explores the immigrant experience; the battle to accept oneself, imperfections and all; and the importance of personal dignity."[6] Claudia Puig of USA Today noted "What will undoubtedly resound powerfully with audiences of Real Women Have Curves, particularly women, is the film's message that there is beauty in all shapes and sizes."[7] One of the few negative reviews the film received was written by Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian, he gave the film a two star rating.[8]

Academia

Real Women Have Curves was received with critical acclaim in the academic sphere for its poignant commentary on challenges facing Latina women today. In a study examining beauty standards for Latinas, three researchers interviewed Mexican-American adolescent girls living in Central California to examine "the nature of appearance culture as a source of girls' perceived beauty standards."[9] The study was published in the July 2015 SAGE Journal of Adolescent Research. Researchers found that "the girls pointed to the media as a major source of beauty ideals. The girls were quite critical of European American girls and women who are attracted to unnaturally thin body shapes depicted in mainstream media. Instead, they [the girls interviewed] admire thick, curvaceous bodies common among women of color in pop culture and Spanish-language media."[9]

America Ferrera became a pop icon for many young women, especially Latinas, because she takes on roles where body image issues are prevalent parts of the film (see Real Women Have Curves, Ugly Betty, How the Garcia Girls Spent their Summer, and The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants). In the HBO documentary The Latino List: Volume 1, Ferrera speaks about her personal experiences growing up in the San Fernando Valley.[10] Ferrera says she remembers watching popular 1990s television shows, "but there were moments that would remind me that I was different from everyone else."[10] Ferrera remembers being bullied for having darker skin or being different than the other Spanish speaking girls but she says "I didn't feel different until someone made an effort to point it out to me."[10] Ferrera went on to say, "when I think about anyone who's marginalized, or made fun of, or dismissed, or hated with some sort of passion; I mean I just see myself, I just think of myself," but she concludes "there's no person or award, validation, that is ever going to make you more worthy than you already are. The times when its been easiest to love myself is when I've put myself in positions to serve others."[10]

In 2013 Juanita Heredia of Northern Arizona University published an article in the journal Mester that discussed the representation of Latinas in Real Women Have Curves and Maria Full of Grace.[11] The journal article states "the Latina protagonists in both visual narratives represent an autonomous voice resisting the institutionalization of patriarchy, be it in the family structure or the labor force as well as the containment of sexual expression, as limited choices for women within the space of the city."[11] The article criticizes Hollywood for not contributing "representations of autonomous and powerful Latina and Latin American women figures in mainstream cinema."[11]

Awards

Won

- 2002 Humanitas Prize, Sundance Film Category, George LaVoo and Josefina Lopez[12]

- 2002 National Board of Review, Special Recognition for excellence in film making[12]

- 2003 Imagen Awards, Best Supporting Actress - Film, Lupe Ontiveros[12]

- 2003 Independent Spirit Award, Producers Award, Effie Brown

- 2002 San Sebastián International Film Festival, Youth Jury Award, Patricia Cardoso[12]

- 2002 Sundance Film Festival, Audience Award, Patricia Cardoso

- 2002 Sundance Film Festival, Special Jury Prize (for acting), America Ferrera and Lupe Ontiveros.[13]

Nominated

- 2002 Sundance Film Festival, Grand Jury Prize, Patricia Cardoso

- 2003 Independent Spirit Award, Best Debut Performance, America Ferrera

- 2003 Young Artist Award, Best Performance in a Feature Film - Leading Young Actress, America Ferrera

See also

- History of the Mexican Americans in Los Angeles

References

- Real Women Have Curves at Box Office Mojo

- Tartaglione, Nancy (December 11, 2019). "National Film Registry Adds 'Purple Rain', 'Clerks', 'Gaslight' & More; 'Boys Don't Cry' One Of Record 7 Pics From Female Helmers". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved December 11, 2019.

- "Real Women Have Curves (2002)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- "Real Women Have Curves". Metacritic. CBS Interactive Inc. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- Mitchel, Elvis (22 March 2002). "Real Women Have Curves (2002) Film Festival Review; Full Figured and Ready to Fight". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- Oppenheimer, Jean. "Curve Ball". dallasobserver.com. Dallas Observer LP. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- Puig, Claudia (25 October 2002). "Real Women Reflects the Real World" (15D). USA Today.

- Bradshaw, Peter (30 January 2003). "Real Women Have Curves". Guardian News and Media Limited. The Guardian. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- Romo, Laura; Mireles-Rios, Rebeca; Hurtado, Aida (9 July 2015). "Cultural, Media, and Peer Influences on Body Beauty Perception of Mexican-American Adolescent Girls". Journal of Adolescent Research: 1–28. doi:10.1177/0743558415594424.

- Greenfield-Sanders, Timothy. "The Latino List: Volume 1". Freemind Beauty & Perfect Day Films. HBO Documentary Films. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- Heredia, Juanita (2013). "From the New Heights: The City and Migrating Latinas in Real Women Have Curves and María Full of Grace". Mester. 1 (42): 3–24. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- "Real Women Have Curves". American Film Showcase. USC School of Cinematic Arts. Retrieved July 30, 2015.

- "Real Women Have Curves". Sundance Institute. 2002 Sundance Film Festival Archives. Retrieved 5 September 2015.