Rauch and Lang

The Rauch & Lang Carriage Company was an American electric automobile manufactured in Cleveland, Ohio, from 1905 to 1920 and Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts, from 1920-1932.[1]

| |

| Automobile Manufacturing | |

| Industry | Automotive |

| Genre | Touring cars |

| Founded | 1905 |

| Founder | Jacob Rauch and Charles E.J. Lang |

| Defunct | 1920 |

| Headquarters | Cleveland, Ohio , |

Area served | United States |

| Products | Vehicles Automotive parts |

History

Jacob J. Rauch came from Bavaria to New York City in the 1840s, eventually making his way to Cleveland, Ohio, where he established a blacksmith's shop on Columbus Rd. in 1853. At the time, the Cincinnati to Cleveland stagecoach traveled by his shop on a daily basis and in no time at all, several hands were hired to man the four fires in Rauch's busy smithy. At that time, Rauch's first assistant, Joseph Rothgery, received a salary of $75 per year.

In 1860, Jacob's son Charles opened up a second shop on Pearl Rd., just southwest of the city on the route of the Columbus to Cleveland stagecoach. Both father and son were skilled blacksmiths and wheelwrights, and the pair began manufacturing carriages and wagons from the two shops.

Jacob J. Rauch was killed at Gettysburg on July 3, 1863 while serving with Cleveland's 8th Regt. Ohio Volunteer Infantry, Gibralter Brigade of the Army of the Potomac (aka Union Army), and young Charles closed down the Columbus Rd shop, concentrating his efforts at Pearl Rd.

Cleveland's population grew exponentially following the American Civil War, and by 1878, the city's inhabitants numbered 160,000, ten times the city's 1853 population. Although Charles had only been active in the firm for a short time, he was clearly in the right place at the right time and by the 1870s his carriage manufactory was Northern Ohio's largest.

For many years Rauch had manufactured a small number of wagons, drays and heavy-duty trucks as well as carriages. Their most popular model was their ice wagon which featured a large polar bear painted by A.M. Willard, a popular artist of the era and one of them received a bronze medal at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876. As did most other carriage builders, Rauch built a large number sleighs for used during the harsh northern winters of which the Buffalo Speed Cutter was their most popular model.

Charles E.J. Lang was born in Cleveland, Ohio in 1858 to wealthy German immigrants. The family was in direct relation to the von Lang's of Germany Karl Heinrich Lang, though they did not utilize the von portion of their surname in America. After graduation from Western Reserve College now known as CWRU Lang was trained as a bookkeeper and it was in this capacity that he was hired by Charles Rauch in 1878. His family had extensive real estate holdings in the Lakewood suburb of Cleveland and he soon proved invaluable to the firm, becoming a partner in 1884. The resulting firm was capitalized with $75,000 and incorporated as the Rauch and Lang Carriage Company, whose board included Charles Rauch, Charles E.J. Lang, Henry Heideloff, Herman Kroll and John Kreifer. Rauch was elected president, and Lang, secretary-treasurer. Rauch and Lang collected $18,000 salary, the other board members, $10,000. A four-story factory was leased at the corner of Pearl Rd. (now West 25th St.) and McLean Sts. for $1,650 per year. Lang was able to bring in additional investments through his family's ties to Andrew Carnegie and Charles E.J. Lang's friend and neighbor John D. Rockefeller.

By 1890, Lang had become the firm's vice-president and a second 4-story building was leased adjacent to the Pearl Rd manufactory. Joseph Rothgery, their very first employee, was now in charge of the finishing department and was on hand whenever a Rauch & Lang carriage was delivered locally. The Ireland, Mather and Hanna families rode in Rauch & Lang carriages, as did most of the region's leading citizens. They specialized in Broughams, Victorias, Stanhopes, opera busses and doctors wagons which sold for between $500 and $2,000.

In 1894 Rauch & Lang posted a profit of $40,000, and introduced a new line of light delivery vehicles that proved to be very popular. In 1903, their Cleveland wareroom became a dealership for the new Buffalo Electric automobile, and within two years, they were manufacturing their own electric vehicles which had been road tested by Joseph Rothgery, who had just celebrated his 50th anniversary with the firm. Initially only a Stanhope was available, but by the end of 1905, a number of coupes and depot wagons had been manufactured, 50 vehicles in all.

Many of the Rauch & Lang Electric's non-coachbuilt components were sourced from Cleveland's Hertner Electric Co. and following a $175,000 recapitalization, Hertner Electric became part of Rauch & Lang in 1907.

Charles E.J. Lang's family was associated with the Lakewood Realty Co., whose president, Charles. L.K. Wieber, provided much of Rauch & Lang's new capital. Wieber became the firm's new vice-president, and the rest of the officers were given a substantial increase in salary at the same time. John H. Hertner, the founder of Hertner Electric Co., and his chief engineer, D.C. Cunningham, were put in charge of the electric vehicle division and from that point on all of the automobile's components were manufactured in-house.

By 1908, they were producing 500 vehicles annually, and had back-orders for 300 more. Consequently, a mechanical engineer was brought in to see what could be done to increase capacity. A year later, the firm was recapitalized to the tune of $1,000,000 and Charles L.F. Wieber was given the title of general manager and a salary of $10,000. A new 340,000 sq. ft. factory was built, and the firm bought an interest in the Motz Clincher Tire and Rubber Co. to insure an adequate supply of tires.

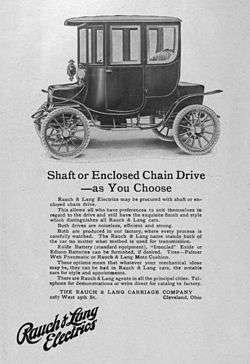

In 1911, the Rauch and Lang Electric was voted the most popular car in San Francisco and Minneapolis and a year later, worm drive was introduced. A Rauch & Lang advertisement penned by Albert Lasker of the Lord & Thomas Advertising Agency stated:

"Again has the Rauch and Lang electric asserted its premiership as Society's chosen car. The success of the new worm drive has been immediate.

"This new feature means continued leadership in driving quality just as the beautiful body lines, rich finish and ultra refinement in every detail have always marked supremacy of Rauch and Lang construction. They are enthusiastic because the Rauch and Lang Straight Type Worm Drive (top mounted), which is superior to all others, means a greater than ever all 'round efficiency, a silence that is manifest, a power economy hitherto unknown and a driving simplicity that appeals to the most timid women. The Rauch and Lang is the highest priced automobile on the market. Its value is readily apparent to those who seek in a car artistic and mechanical perfection."

Later that year they were sued by their cross-town rivals, the Baker Electric Vehicle Co., for infringing upon Baker's patented drivetrain.

In 1912, 356,000 passenger cars were produced in the United States, and towards the end of the year, Charles Rauch, the founding father of Rauch & Lang, passed away. On November 26, 1912, the board of directors elected Charles C.F. Wieber president and general manager of the Rauch and Lang Carriage Company. Charles E.J. Lang became vice-president-treasurer and F. W. Treadway the firm's new secretary. It was during this time that both Lang and Rauch moved their families to the Eastside of Cleveland, building large mansions on the exclusive Euclid Avenue, also known as Millionaire's Row.

The October 23, 1913, issue of the Automobile announced that Rauch and Lang had introduced a radically new drive principle, the bevel gear transmission. They also introduced the dual control coach, a five-passenger, $3200 electric sedan that could be driven from either the front seat, the rear seat, or both, a safety switch deactivated the forward controls if the revolving front seat was in any position other than forward.

A period Rauch & Lang ad boasted: "Whatever your ideas today, you are certain to come to the conclusion, sooner or later, that an enclosed automobile like the Rauch & Lang Electric combines all the desirable features and eliminates all the well-known annoyances and much of the expense incident to gasoline cars."

The introduction of Charles Kettering's self-starter in 1912 marked the beginning of the end for the electric automobile and by 1915 their share of the burgeoning automobile marketplace had fallen dramatically. Despite their earlier lawsuit, Cleveland's two electric vehicle manufacturers decided to merge, hoping that by streamlining their engineering and manufacturing operations, they might survive.

On June 10, 1915, the Automobile announced the merger, and the resulting firm, the Baker, Rauch & Lang Co. was capitalized for $2,500,000. The officers were: Charles C.F. Wieber, president; Frederick R. White, first vice-president; Charles E. J. Lang, second vice-president; R. C. Norton, treasurer; G. H. Kelly, secretary; F. W. Treadway, counsel. Fred R. White and Rollin C. White, two of the owners of the White Motor Co., were early investors in Baker, and as such were represented on the new Baker, Rauch & Lang Co.'s board of directors.

It soon became apparent that the days of the electric car were numbered and despite both firm's previous success, a decision was made to look for additional products to produce in their large Cleveland factories.

As early as 1902, Walter C. Baker and Justus B. Entz were independently searching for methods to simplify the operation of the motor vehicle. Baker concentrated his efforts on the electric vehicle, Entz on the electromagnetic transmission, a device that used a magnetic field to drive a propeller or driveshaft. By varying the intensity of the field, a vehicle could go faster or slower without using a clutch. Baker purchased the rights to the Entz patents in 1912, and licensed them to R.M. Owen & Company, the producer of the Owen Magnetic, a gasoline-engined car that utilized an Entz transmission.

It was decided that Baker, Rauch & Lang would produce the Owen Magnetic in Cleveland, so in December 1915, they absorbed R.M. Owen & Co. and relocated it to Cleveland. Raymond M. Owen became a vice-president of Baker, Rauch & Lang and was placed in charge of sales for the Owen Magnetic whose drivetrains were built in the former West 83rd Street Baker plant, the coachwork in the former Rauch & Lang facilities.

The new vehicle attracted the attention of the General Electric Company, and in 1916 they contributed $2,500,000 to the venture which increased Baker, Rauch & Lang's capitalization to $5,000,000. In return, General Electric was given exclusive contracts for the vehicle's electrical components and got three seats on their board of directors.

The Owen Magnetic proved popular and was available in nine versions, four on a 29 hp 125-inch wheelbase and five on a 34 hp 136-inch wheelbase – all powered by a six-cylinder gasoline motor. Rauch & Lang's coachwork was amongst the finest available, and the attractive cars featured styling similar to that of the finest European chassis. The cars were priced from $3100 to $5700 and were owned by many celebrities including: Enrico Caruso, John McCormack, Arthur Brisbane and Anthony Joseph Drexel Biddle.

Comedian, Tonight Show host, and serious automotive collector, Jay Leno, owns a 1917 Owen Magnetic and wrote about it in his Popular Mechanics column of August 13, 2002: "The engine's only job is to turn the magnetic field, which then turns the generator, which runs the rear wheels. It's not a hybrid, it's driven by a conventional engine. It was an automatic transmission 30 years ahead of its time."

Baker, Rauch & Lang built most of the Owen-Magnetic's coachwork, however in 1916-1917 a small series of open sports tourers were built by Holbrook that featured distinctive flat-topped and angled front and rear fenders.

Unfortunately the impending war forced Baker, Rauch & Lang to abandon full production of the vehicle and much of their workforce geared up to manufacture electric tractors, trucks and bomb-handling equipment for the US Armed Forces. Baker had experimented with electric industrial trucks prior to the merger and following the Armistice, Baker, Rauch & Lang's industrial trucks and tractors were placed on the market and eventually became the firm's most popular product.

On January 13, 1919, Charles C.F. Wieber was made chairman of the board of directors and Frederick R. White was named president. E. J. Bartlett was named a vice-president and general manager. Notably absent from the reorganized board was Charles E. J. Lang and Raymond M. Owen, the firm's two vice-presidents. Both Mr. Lang and Mr. Owen were bought out of their shares of the company for over $2 million USD each. Raymond Owen left for a life of retirement and leisure, while Lang continued to assist the board as an honorary trustee through the mid 1920s. Although the legal name of the firm continued to be Baker, Rauch & Lang Co., following Lang's departure their products were marketed as either Raulang or Baker-Raulang products although they wouldn’t change their legal name until 1937. The board continued to use Lang's close personal relationship with the Astor family and market the luxury vehicles at shows hosted at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York City.

In exchange for his stock, Owen had been given the rights to manufacture the Owen-Magnetic on his own and relocated to Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania where he made an arrangement with Frank Matheson to build them in the former Matheson automobile plant. A couple hundred more Owen Magnetics were completed in Pennsylvania before the firm when bankrupt in 1921. Much of Owen's 1920 and 1921 output was sent to England re-badged as the Crown Ensign (aka Crown Magnetic). Crown was the name of the British importer Crown Limited who also manufactured the British Ensign. Total Owen Magnetic production from 1915 to 1921 was approximately 975 vehicles, of which only a handful survive.

Charles E. J. Lang sold his interest in Baker, Rauch & Lang and organized the Lang Body Company with the proceeds. Early on, Lang received several large orders from Dodge and Lincoln for production bodies, but was out of business by 1924.

The electric automobile division of Baker, Rauch & Lang was sold to Raymond S. Deering, a Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts businessman who also owned the former factory and assets of the defunct Stevens-Duryea Motor Co. He reorganized that firm in 1919 as Stevens-Duryea Inc. and started production of a new Stevens-Duryea automobile. Using the Rauch & Lang trade name, Deering manufactured a small number of electric taxicabs in a new plant that was built next to the existing Stevens-Duryea factory. Unfortunately, a number of financial setbacks plagued the Deering enterprises and by 1922, both firms were in receivership.

In another one of the great coincidences is US automotive history, Raymond M. Owen, the former builder of the Owen Magnetic and current president of the Syracuse Owen-Dyneto Electric Corp., purchased Stevens-Duryea Inc. for $450,000, and started producing new Stevens-Duryea automobiles in 1924 as Stevens-Duryea Motors Inc. Robert W. Stanley was placed in charge of the Rauch & Lang Inc. subsidiary and Owen's brother Ralph was placed in charge of Stevens-Duryea. Only 53 Stevens-Duryea cars were produced through 1927, and only a handful of Rauch & Lang taxis.

However the firm survived for a few more years building and repairing truck, bus and van bodies for area firms. In August, 1928, half of the Rauch & Lang plant was leased to the Moth Aircraft Corporation (the US subsidiary of DeHaviland Aircraft, Ltd.) to build the Gypsy Moth airplane.

Between 1929 and 1930, Raymond M. Owen’ Rauch & Lang Inc. produced a couple of experimental automobiles with electronic automatic transmissions with backing from a disabled millionaire named Colonel Edward H.R. Green. Green was the incredibly wealthy son of the Witch of Wall Street, Hetty Green. When Edward was only 10, he severely injured a leg while sledding. Because his tight-fisted mother refused to pay for a doctor to treat the leg, gangrene developed, and the leg had to be amputated. He had the last laugh as he spent her $95 million fortune as fast as he could following her death in 1916.

Green had a portfolio of General Electric stock and its board of directors put him in touch with Owen, as GE had once had an interest in his Owen-Magnetic automobile. A 1929 Stearns-Knight Model M-6-80 cabriolet-roadster served as the basis for the first prototype. The car had a 60 hp Knight sleeve-valve engine and with lots of assistance from General Electric engineers, Owen easily converted the car over to electric drive.

The original convertible coupe prototype had an incredibly awkward-looking body that allowed Green to enter and exit the vehicle without stooping - the windshield was purportedly 7 feet tall. However, two additional prototypes were built with more normal bodies - a brougham and a sedan – that would have been more palatable to prospective clients. Green sunk over $1,000,000 into the project, and the idea of building a taxicab using the system was toyed with. However the entire project was shelved by all parties involved when it became apparent the Depression wasn’t going away. However, Colonel Green did get his custom-built automatic drive automobile, albeit only one example.

Remarkably one of the prototypes - the sedan - still exists and was featured at the Silverado Concours d’Elegance in 2001.

Rauch & Lang Inc. survived and became the New England distributor for White Motors’ buses and in another coincidence, the New England repair depot for Raulang commercial bodies. Stevens-Duryea survived as a holding company, but was no longer active in the automobile business.

Following their 1919 reorganization, Baker, Rauch & Lang concentrated their efforts in three areas, the first and most important was their electric industrial truck division, the second, their production body business which was now known as the Raulang Body Division of Baker, Rauch & Lang.

Rauch & Lang Carriage Co. had a well-earned reputation for their coachwork, and many of the region's automakers such as Biddle-Crane, Cadillac, Duesenberg, Franklin, Gardner (1930), Hupmobile, Jordan, Lexington, Packard, Peerless, Reo, Ruxton (1930), Stanley, Stearns-Knight and Wills Ste. Claire, would become Raulang customers. Other activities of the body division included the design and building of prototype models for the large automobile manufacturers in Detroit. Not only did Raulang produce automobile bodies, through 1928 they built bus bodies for their distant cousin, the White Motor Co., as well as for Yellow Coach, General Motors and Reo.

Additional bodybuilding capacity was acquired in January 1924 with the purchase the former Leon Rubay Co. factory. Although Rubay went out of business in 1923, Baker-Raulang continued to supply leftover Rubay bodies to Rubay's former customers and as late as 1927, a Rubay-designed town car body was used on Moon's Diana Town Car. Raulang even made an appearance at the 1929 Auto Salons where they displayed a custom-bodied Ruxton Town Car. Although Budd built all of the Ruxton's closed production bodies, Raulang furnished the bodies for Ruxton's roadster, their most popular model.

Baker, Rauch & Lang's Industrial Truck Division introduced a number of new products in the early twenties including a ram truck for carrying heavy steel coils as well as a line of low-lift platform truck and cranes. The Hy-Lift platform truck was introduced in 1922, and an articulated sheet handler in 1923. This innovative electric unit had a pivoted platform that could load 10-foot steel sheets through a standard seven-foot railroad car door. They also developed a duplex or "knee-action" compensating suspension that pre-dated GM's duBonnet system by a number of years.

By 1926, all of the firm's original officers had retired, replaced by a new group who would serve the company into the 1950s. E.J. Bartlett was president; E.H. Remde, chief engineer; H.A. Schultz, production superintendent; J.W. Moran, assistant treasurer; and Carl E. Geiger, purchasing agent.

Prior to 1929, all of Ford's station wagons were produced by custom body shops such as Cantrell, York-Hoover, Waterloo and others utilizing chassis purchased from independent Ford dealers. Ford decided to provide a factory station wagon for the new Model A, marking the first time a manufacturer mass-produced a station wagon on their own assembly line. Murray produced 4,954 examples of Ford's new $695 Model 150-A Station Wagon in 1929. The following year, A new body style, the 150-B, was introduced and the contract was split between Murray and Baker-Raulang in Cleveland, Ohio. Murray was swamped with other Ford projects so Baker-Raulang built the lion's share of the 6,363 Model 150-B bodies built in 1930-1931. 1932 Ford Model B station wagon bodies were all built by Baker-Raulang, as Murray was still overwhelmed with bodywork destined for the new 1932 Ford.

As Ford's Iron Mountain facility was ill-equipped to manufacture the complicated wooden framework for the Model 150 bodies, the millwork was subcontracted to the Mengel Body Company of Louisville, Kentucky, a medium-sized production body builder who had previously supplied Model T coachwork for Ford's Louisville branch. Iron Mountain shipped kiln-dried lumber to Mengel who milled and assembled the various subcomponents which were then shipped to either Murray or Baker-Raulang for final assembly. Rather than shipping the bare Model A chassis to Raulang, Ford opted to have Murray and Raulang assemble and finish the bodies, then ship them to a Ford assembly plant where they were mated to a waiting chassis. The bodies produced by Raulang were assembled without cowls as Raulang lacked the deep-draw presses needed to produce them and special bracing was installed to prevent damage during shipping to Ford. Baker-Raulang also built the very rare 1931 Model A Traveler's Unit, a 2-door Woody camper with screen-side panels based on the Model A Special Delivery Body.

From the late twenties through the late thirties, Raulang's "woodie" bodies were built for other chassis in addition to Ford. Available through independent automobile dealers and commercial body distributors, Raulang woodies enjoyed the same good reputation as their carriages and electric automobiles had years earlier. Series-built bodies were also produced in small quantities for other manufacturers such as the 100 built for Packard in 1937.

The success of the woody wagon body program for Ford brought them additional contracts for other Ford commercial bodies which was fortunate as the lack of deep-draw metal stamping equipment effectively put them out of the production automobile body business.

Ford's Type 315-A "Standrive" route delivery trucks featured a Raulang body upon the model's introduction in 1931. The "Standrive" models were built using a special Ford Model AA-112 drop-center chassis, which allowed a very low walk-in and standing driving position.

Ford introduced their new line of commercial chassis in 1932. Now available with the new flathead V-8 and designated Model B or BB the new double drop chassis featured better springs, a new low-slung appearance and the possibility of substantially more power.

Raulang built a number of new bodies to take advantage of the new Ford commercial chassis. Their Model 519 Delivery body resembled the bodies found on today's UPS trucks - sans the cab over engine front end. The front of the body attached directly to the Ford cowl-chassis and offered department stores and parcel delivery services a whopping 260 cubic feet of cargo capacity (minus the driver's compartment) when built on a 133 1/2" chassis. An even larger body was available for Ford's 157" chassis that advertised over 360 cubic feet of storage.

Early in the 1930s Baker, Rauch & Lang introduced sit-down controls on many of their electric industrial trucks and fork lifts and by 1936 their fork-lifts included the articulated tail first introduced in 1923. Their fork lifts were available in lift capacities of up to 6,000 lbs., and when equipped with the "wiggle-tail" system, they could operate in aisles as narrow as 10 feet.

Although they had been known as Baker-Raulang for many years, it wasn’t until 1937 that the officially changed their name from Baker, Rauch & Lang Co. Along with the official change of name came a new line of gasoline-powered industrial trucks as well as a new line of milk floats and inner-city delivery vehicles to compete with the popular models built by the Detroit-Electric Co.

Baker-Raulang introduced a new line of all-metal utility bodies for electric light, gas and telephone companies that were marketed under the Baker brand name.

When the country's manufacturers began to ramp up for World War II, Baker-Raulang was one of a handful of firms that produced electric industrial trucks and fork-lifts. In 1940 alone, more electric industrial trucks were ordered by the government than had been produced since their introduction in the teens. Critical shortages of copper combined with a lack of manufacturing capacity led Baker-Raulang (and the government) to the realization that gasoline powered truck and forklifts were the answer. Baker-Raulang produced as many electric and gasoline-powered vehicles as possible and helped regional automobile manufacturers re-tool in order to produce enough gasoline-powered fork lifts and bomb handling equipment to meet the Government's requirements.

The Raulang body plant also contributed to the war effort, producing hundreds of bodies for reconnaissance cars and personnel carriers. The firm's wartime efforts earned them the coveted "E" Army-Navy award for excellence. Another unexpected tribute came from the enemy; one German report referred to the fork lift as "America's most formidable secret weapon".

Following the war, Baker-Raulang found the market for their fork lifts and industrial trucks was strong, but unfortunately by helping other manufacturers produce industrial trucks for the war effort, they had unwittingly created competition where it had not existed previously. Additionally, too much of their products were custom-made for customers with peculiar handling problems, which put them in a weak position to compete with their mass-produced competition. However, by 1947 a number of new mass-produced electric and gasoline-powered fork-lifts and yard trucks were put into production, and a year later demand was so high that they decided to move their industrial truck manufacturing operations to their West 80th St. plant, which formerly made truck bodies. By 1950, a new addition to the West 80th St. plant had been completed and the original West 25th St factory was sold.

Late in 1951 Baker introduced a brand-new line of gasoline-powered industrial trucks and fork lifts, and were once again major suppliers to the US Government during the Korean War.

On the 100th anniversary of the firm in (1853-1953), Baker-Raulang commissioned author R. Thomas Willson to produce a small book commemorating the event. Unfortunately, by that time, Baker-Raulang had already been out of the coach building business for a number of years.

In 1953 Baker-Raulang purchased the Lull Mfg. Co. of Minneapolis, Minnesota, a heavy-duty construction equipment manufacturer in order to offer their customers a wide range of materials handling equipment. The Otis Elevator Co. - who incidentally was also started in 1853 - purchased the entire Baker-Raulang operation in 1954. In 1967, Otis acquired the Moto-Truc Co., another Cleveland-based industrial truck manufacturer who had been building pallet lift trucks since the Thirties.

Otis sold their Baker-Raulang & Moto Truc divisions in 1975, to Linde AG, the world's largest manufacturer of fork lifts and industrial material handling vehicles, renaming it the Baker Material Handling Corp.

By combining the best American and European design concepts, the merger marked a new era in lift truck technology. Subsequent Linde-Baker innovations include a true hydrostatic drive for internal combustion powered trucks; an air-cooled, low pollution diesel engine; a transverse drive electric truck with 100% solid-state controls; a dual-drive 3-wheel electric truck, and a series of turret trucks for narrow aisles and high lift applications.

In 1999, Baker Material Handling Corp. became Linde Lift Truck Corporation who continue to produce large capacity engine-powered trucks and materials handling equipment in their Cleveland, Ohio plant.

Summary:

Wagon builders Charles Rauch and Charles E.J. Lang began producing electrically powered automobiles in 1905 with a stanhope style vehicle.[1] By 1908 they were producing 500 automobiles a year.[1] In 1916, another Cleveland luxury automobile makerBaker Electric merged with Rauch and Lang.[2] After 1919, the automobiles were known as Raulangs.[2]

Owen Magnetic

The Owen Magnetic was manufactured in the Rauch and Lang factory from 1916-1919.[1]

Smithsonian

A Rauch and Lang automobile is currently on display in the Smithsonian Institution Rauch and Lang vehicle

Chicopee Falls years

In 1920, the Stevens-Duryea company bought out Rauch and Lang and moved production to Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts. The company focused on producing taxi cabs and offered both electric and gasoline versions. Automobile production ended in 1928, but the company continued producing trucks and buses for a few more years.[1]

See also

- List of defunct United States automobile manufacturers

- History of the electric vehicle

Other early electric vehicles

References

- Kimes, Beverly Rae; Clark Jr; Henry Austin (1996). Standard Catalog of American Cars: 1805–1942. Iola, WI: Krause Publications. p. 1264. ISBN 978-0-87341-428-9.

- Wise, David Burgress (2000). The New Illustrated Encyclopedia of Automobiles. Chartwell Books. ISBN 0-7858-1106-0.

External links

- Secondhandgarage.com: Rauch and Lang company history

- Ghostsofdc.org: What Happened to the Electric Car? Buy a Rauch & Lang Coupe (1909)

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. OH-11, "Cleveland Automobile Industry, Cleveland, Cuyahoga County, OH", 34 data pages

- HAER No. OH-11-B, "Rauch & Lang Carriage Company, West Twenty-fifth Street & Monroe Avenue, Cleveland, Cuyahoga County, OH", 17 photos, 17 data pages, 1 photo caption page

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rauch and Lang vehicles. |