Ramsey Psalter

The Psalter of Oswald also called the Ramsey Psalter (British Library, Harley MS 2904) is an Anglo-Saxon illuminated psalter of the last quarter of the tenth century.[1] Its script and decoration suggest that it was made at Winchester, but certain liturgical features have suggested that it was intended for use at the Benedictine monastery of Ramsey Abbey, or for the personal use of Ramsey's founder St Oswald.

_Initium.jpg)

The litany includes a gold-lettered triple invocation of St Benedict of Nursia, and at the time of writing, probably before Oswald's death in 992, Ramsey was the only English monastery dedicated to this saint. A "Psalter of St Oswald" was listed in a 14th-century catalogue of the library at Ramsey.[2] This manuscript is not to be confused with another Ramsey Psalter in the Pierpont Morgan Library, New York (MS M. 302), made between 1286 and 1316.

The text is a Latin psalter using the Gallican version. The "elegant English caroline minuscule" of the script inspired the influential "foundational hand" developed by the 20th-century calligrapher Edward Johnston.[3]

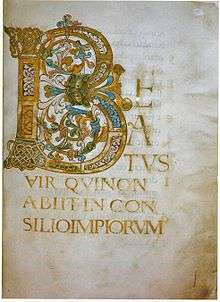

The two most famous illuminated pages are at the start of the manuscript and are illustrated here and discussed below. Apart from another very large illuminated initial at the start of Psalm 101, the rest of the illumination consists of smaller decorated initials with colour at the start of each psalm, and gold initials for each verse.[4]

Illumination

Unsurprisingly for a manuscript with such strong connections to Oswald, a leader of the English Benedictine Reform, the decoration shows the "Winchester style" associated with the reform, including continental influences. The famous tinted line drawing of the Crucifixion is in the version of the English form of the coloured outline drawing that draws on the style of the Utrecht Psalter, and the painted miniatures use sprawling acanthus leaves, the Winchester version of decoration derived from Carolingian and Ottonian art.[5] Equally, however, there is use of Insular interlace, restricted to the ends of the vertical element of the Beatus initial of Psalm 1 and the "D" at Psalm 101.[6]

The artist of the Crucifixion miniature seems also to have worked at Fleury Abbey, where both Oswald and his uncle, Archbishop Oda of Canterbury, had trained,[7] as well as the Abbey of Saint Bertin, Saint-Omer, both of these in France. At St Bertin he worked on the Boulogne Gospels (municipal library there, MS 11) and at Fleury on the Harley Aratea (BL, Harley MS 2506).[8]

The figure of Christ is very similar to that on an Anglo-Saxon reliquary cross in the Victoria and Albert Museum, which was set on a small reliquary in Germany around 1000.[9] The Beatus initial appears to be the first to use the "lion-mask" in the bridge,[10] which was to be widely copied in England and abroad.[11]

Notes

- Brown, 119

- BL

- Brown, 120

- BL

- Backhouse, Turner and Webster, 60

- Pächt, 86

- Backhouse, Turner and Webster, 60

- Brown, 118-123. Further manuscripts he worked on are given in Dodwell, C.R.; The Pictorial arts of the West, 800–1200, 1993, Yale UP, ISBN 0300064934

- Wilson, David M.; Anglo-Saxon Art: From The Seventh Century To The Norman Conquest, pp. 194-195, Thames and Hudson (US edn. Overlook Press), 1984.

- Webster, Leslie, Anglo-Saxon Art, p. 177, 2012, British Museum Press, ISBN 9780714128092; Brown, 119; for example there is a mask in the very similar drawn Beatus initial in the Winchcombe Psalter, Cambridge University Library, MS Ff.1.23, f. 5, dated 2nd quarter of the 11th century, see: Backhouse, Turner and Webster, 78 and illustrated at 80.

- Pächt, 86-89

References

- J. Backhouse, D. H. Turner and L. Webster, eds.: The Golden Age of Anglo-Saxon Art, 966-1066. London: British Museum, 1984.

- British Library: Detailed record for Harley 2904 in the BL Catalogue of illuminated manuscript (with several images and bibliography).

- Michelle P. Brown: Manuscripts from the Anglo-Saxon Age. London: British Library, 2007. ISBN 9780712306805, p. 119.

- Otto Pächt: Book Illumination in the Middle Ages: an introduction. London: Harvey Miller, 1986. ISBN 0199210608.

Further reading

- Holcomb, M. (2009). Pen and Parchment : Drawing in the Middle Ages. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. (see index)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Psalter of Oswald (c.975-1000) - BL Harley MS 2904. |

- images on ramseyabbey.co.uk

- The Great Benedictine Abbey of Ramsey