Raku ware

Raku ware (楽焼, raku-yaki) is a type of Japanese pottery traditionally used in Japanese tea ceremonies, most often in the form of chawan tea bowls. It is traditionally characterised by being hand-shaped rather than thrown, fairly porous vessels, which result from low firing temperatures, lead glazes and the removal of pieces from the kiln while still glowing hot. In the traditional Japanese process, the fired raku piece is removed from the hot kiln and is allowed to cool in the open air.

The Western version of raku was developed in the 20th century by studio potters. Typically wares are fired at a high temperature, and after removing pieces from the kiln, the wares are placed in an open-air container filled with combustible material, which is not a traditional Raku practice in Japan. The Western process can give a great variety of colors and surface effects, making it very popular with studio and amateur potters.

History

Raku means "enjoyment".

In the 16th century, Sen no Rikyū, the Japanese tea master, was involved with the construction of the Jurakudai and had a tile-maker, named Chōjirō, produce hand-moulded tea bowls for use in the wabi-styled tea ceremony that was Rikyū's ideal. The resulting tea bowls made by Chōjirō were initially referred to as "ima-yaki" ("contemporary ware") and were also distinguished as Juraku-yaki, from the red clay (Juraku) that they employed. Hideyoshi presented Jokei, Chōjirō's son, with a seal that bore the Chinese character for raku.[1] Raku then became the name of the family that produced the wares. Both the name and the ceramic style have been passed down through the family (sometimes by adoption) to the present 15th generation (Kichizaemon). The name and the style of ware has become influential in both Japanese culture and literature.

In Japan, there are "branch kilns" (wakigama), in the raku-ware tradition, that have been founded by Raku-family members or porters who apprenticed at the head family's studio. One of the most well-known of these is Ōhi-yaki (Ōhi ware).

After the publication of a manual in the 18th century, raku ware was also made in numerous workshops by amateur potters and tea practitioners in Kyoto, and by professional and amateur potters around Japan.

Raku ware marked an important point in the historical development of Japanese ceramics, as it was the first ware to use a seal mark and the first to focus on close collaboration between potter and patron. Other famous Japanese clay artists of this period include Dōnyū (grandson of Chōjirō, also known as Nonkō; 1574–1656), Hon'ami Kōetsu (1556–1637) and Ogata Kenzan (1663–1743).

It influenced Hōraku ware from Nagoya, Owari province in the later Edo period.

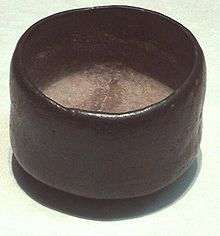

Black Raku-style chawan, used for thick tea, Azuchi–Momoyama period, 16th century

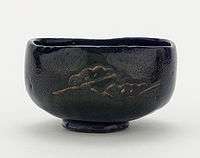

Black Raku-style chawan, used for thick tea, Azuchi–Momoyama period, 16th century_with_Crane_Design_LACMA_M.2007.7.2_(5_of_5).jpg) Black Raku teabowl "aged pine (shōrei) with crane design by Raku IX (Ryōnyū), Edo period, c. 1810–1838

Black Raku teabowl "aged pine (shōrei) with crane design by Raku IX (Ryōnyū), Edo period, c. 1810–1838

Western raku

Bernard Leach is credited with bringing Raku to the west. In 1911 he attended a garden party in Tokyo which included a traditional tea ceremony and Raku firing. This was his first experience of ceramics. Although he continued to experimenting with Raku firing for a few years following his returned to England in 1920 - the technique was largely forgotten after the 1930s.

Raku became popular with American potters in the late 1950s with the help of Paul Soldner. Americans kept the general firing process, that is, heating the pottery quickly to high temperatures and cooling it quickly, but continued to form their own unique style of raku.

Raku's unpredictable results and intense color attracts modern potters. These patterns and color result from the harsh cooling process and the amount of oxygen that is allowed to reach the pottery. Depending on what effect the artist wants, the pottery is either instantly cooled in water, cooled slowly in the open air, or placed in a barrel filled with combustible material, such as newspaper, covered, and allowed to smoke.[2] Water immediately cools the pottery, stopping the chemical reactions of the glaze and fixing the colors. The combustible material results in smoke, which stains the unglazed portions of the pottery black. The amount of oxygen that is allowed during the firing and cooling process affects the resulting color of the glaze and the amount of crackle.

Unlike traditional Japanese raku, which is mainly hand built bowls of modest design, western raku tends to be vibrant in color, and comes in many shapes and sizes. Western raku can be anything from an elegant vase, to an eccentric abstract sculpture. Although some do hand build, most western potters use throwing wheels while creating their raku piece. Western culture has even created a new sub branch of raku called horse hair raku. These pieces are often white with squiggly black lines and smoke-like smudges. These effects are created by placing horse hair, feathers, or even sugar on the pottery as it is removed from the kiln and still extremely hot.

Amongst some of the western raku artists are the French ceramist Claude Champy, who received the Suntory Museum Grand Prix. Jane Malvisi is a British artist making raku figurines.[3]

Pot with an example of horsehair raku technique. The vessel was taken out of the kiln at 732 Celsius and horsehair applied on, which burned into it.

Pot with an example of horsehair raku technique. The vessel was taken out of the kiln at 732 Celsius and horsehair applied on, which burned into it. Made by Ruthann Hurwitz (The Village Potter) in the Western style of Raku. It was built with the coil and pinch method, glazed, then fired. It was removed from the 1800 degree kiln while red hot and placed into containers with combustibles, then covered where reduction takes place, "smoking" the pottery.

Made by Ruthann Hurwitz (The Village Potter) in the Western style of Raku. It was built with the coil and pinch method, glazed, then fired. It was removed from the 1800 degree kiln while red hot and placed into containers with combustibles, then covered where reduction takes place, "smoking" the pottery.

Kilns and firing

The first Japanese-style kiln in the west was built by Tsuronosuke Matsubayashi at Leach Pottery, St Ives in 1922.[4]

The type and the size of kilns that are used in raku are crucial in the outcome. One aspect that can affect the results is the use of electric versus gas kilns. Electric kilns allow easy temperature control. Gas kilns, which comprise brick or ceramic fibers, can be used in either oxidation or reduction firing and use propane or natural gas. Gas kilns also heat more quickly than electric kilns, but it is more difficult to maintain temperature control. There is a note-worthy difference when using an updraft kiln rather than a downdraft kiln. An updraft kiln has shelves that trap heat. This effect creates uneven temperatures throughout the kiln. Conversely, a downdraft kiln pulls air down a separate stack on the side and allows a more even temperature throughout and allows the work to be layered on shelves.[5]

It is important for a kiln to have a door that is easily opened and closed, because, when the artwork in the kiln has reached the right temperature (over 1000 degrees Celsius), it must be quickly removed and put in a metal or tin container with combustible material, which reduces the pot and leaves certain colors and patterns.

The use of a reduction chamber at the end of the raku firing was introduced by the American potter Paul Soldner in the 1960s to compensate for the difference in atmosphere between wood-fired Japanese raku kilns and gas-fired American kilns. Typically, pieces removed from the hot kiln are placed in masses of combustible material (e.g., straw, sawdust, or newspaper) to provide a reducing atmosphere for the glaze and to stain the exposed body surface with carbon.

Western raku potters rarely use lead as a glaze ingredient, due to its serious level of toxicity, but may use other metals as glaze ingredients. Japanese potters substitute a non-lead frit. Although almost any low-fire glaze can be used, potters often use specially formulated glaze recipes that "crackle" or craze (present a cracked appearance), because the crazing lines take on a dark color from the carbon.

Western raku is typically made from a stoneware clay body, bisque fired at 900 °C (1,650 °F) and glost or glaze fired (the final firing) between 800–1,000 °C (1,470–1,830 °F), which falls into the cone 06 firing temperature range. The process is known for its unpredictability, particularly when reduction is forced, and pieces may crack or even explode due to thermal shock. Pots may be returned to the kiln to re-oxidize if firing results do not meet the potter's expectations, although each successive firing has a high chance of weakening the overall structural integrity of the pot. Pots that are exposed to thermal shock multiple times can break apart in the kiln, as they are removed from the kiln, or when they are in the reduction chamber.

The glaze firing times for raku ware are short: an hour or two as opposed to up to 16 hours for high-temperature cone 10 stoneware firings. This is due to several factors: raku glazes mature at a much lower temperature (under 980 °C or 1,800 °F, as opposed to almost 1,260 °C or 2,300 °F for high-fire stoneware); kiln temperatures can be raised rapidly; and the kiln is loaded and unloaded while hot and can be kept hot between firings.

Because temperature changes are rapid during the raku process, clay bodies used for raku ware must be able to cope with significant thermal stress. The usual way to add strength to the clay body and to reduce thermal expansion is to incorporate a high percentage of quartz, grog, or kyanite into the body before the pot is formed. At high additions, quartz can increase the risk of dunting or shivering. Therefore, kyanite is often the preferred material, as it contributes both mechanical strength and, in amounts up to 20%, significantly reduces thermal expansion. Although any clay body can be used, white stoneware clay bodies are unsuitable for the western raku process unless some material is added to deal with thermal shock. Porcelain, however, is often used but it must be thinly thrown.

Aesthetic considerations include clay color and fired surface texture, as well as the clay's chemical interaction with raku glazes.

In a craft conference in Kyoto in 1979, a heated debate sprang up between Western raku artists Paul Soldner and the youngest in the dynastic raku succession, Kichiemon, (of the fourteenth generation of the "Raku" family of potters) concerning the right to use the title "raku". The Japanese artists maintain that any work by other craftsman should hold their own name, (i.e., Soldner-ware, Hirsh-ware), as that was how "raku" was intended.[6]

Raku in the west has been abstracted and is now a more philosophical approach with the emphasis on the spontaneity of surface pattern creation rather than purely a firing technique. Consequently, this has expanded its application from pots to sculptural ceramics.

Reduction process

Reduction firing is when the kiln atmosphere, which is full of combustible material, is heated up. "Reduction is incomplete combustion of fuel, caused by a shortage of oxygen, which produces carbon monoxide" (Arbuckle, 4) Eventually, all of the available oxygen is used. This then draws oxygen from the glaze and the clay to allow the reaction to continue. Oxygen serves as the limiting reactant in this scenario because the reaction that creates fire needs a constant supply of it to continue; when the glaze and the clay come out hardened, this means that the oxygen was subtracted from the glaze and the clay to accommodate the lack of oxygen in the atmosphere. Consequently, the Raku piece appears black or white, which depends upon the amount of oxygen that was lost from each area of the piece. The empty spaces that occur from the reduction of oxygen are filled in by carbon molecules in the atmosphere of the container, which makes the piece blacker in spots where more oxygen was retracted.[7][8]

Raku reduction

In the western style of raku firing, the aluminium container acts as a reduction chamber, which is a container that allows the carbon dioxide to pass through a small hole.[9] A reduction atmosphere is created by closing the container.[9] A reduction atmosphere induces a reaction between oxygen and the clay minerals, which affects the color.[10] It also affects the metal elements of the glaze. Reduction is a decrease in oxidation number.[10] Closing the can reduces the oxygen content after the combustible materials such as sawdust catch fire and forces the reaction to pull oxygen from the glazes and the clay minerals.[10] For example, luster gets its color from deprivation of oxygen. The reduction agent is a substance from which electrons are being taken by another substance.[10] The reaction uses oxygen from the atmosphere within the reduction tube, and, to continue, it receives the rest of the oxygen from the glazes.[9] This leaves ions and iridescent luster behind. This creates a metallic effect. Pieces with no glaze have nowhere to get the oxygen from, so they take it from clay minerals. This atmosphere will turn clay black, making a matte color.

Design considerations

Raku is a unique form of pottery making; what makes it unique is the range of designs that can be created by simply altering certain variables. These variables—which include wax resist, glazes, slips, temperature, and timing[11]—ultimately determine the outcome when firing a piece of clay.

Wax resist: which is painted over the bare untainted clay, results in the suspension of wax in water[12] before the raku glaze goes on. This is done so that the glaze does not cover the area where the wax resist was applied, thus creating a design. When in the kiln, the wax melts off and the carbon, that results from oxygen reduction, replaces the wax.[11] This is the result of the combustion reaction. Raku glazes contain alumina, which has a very high melting point. Therefore, carbon will not replace the glaze as it does the melted wax. Any unglazed areas turn black due to the carbon given off from the reduction of oxygen. Next, the clay is moved from the kiln to a container, usually a trashcan, which contains combustible organic materials such as leaves, sawdust, or paper.

Crackle glazes: is a glaze with a clear base that contain metallic compounds to add color. Metals such as copper, iron, and cobalt; which produce different colors. After the glaze has reached a certain temperature, the metal in the glaze reacts taking on a specific color.[12] For example, cobalt produces dark-blue, and copper produces green but can also produce a red when the oxygen in the glaze is completely gone.[11] Once the lid of the container is closed, the reduction oxidation (redox) process begins.[12] The temperature change from the kiln to the container is where the magic of raku occurs. The change in temperature and in the redox sometimes cause cracking or crazing. Crazing is a consistent cracking in the glaze of a piece, as is seen on the white crackle glaze. This either enhances or detracts from the design. The timing of removal and placement in water directly affects the shades of each color.[11]

Copper glazes: are treated completely different than crackle glazes. While with the crackle glazes you want the piece to go through an oxidation process and to cool so the glaze will crackle while transferring from the kiln to the reduction chamber, the copper glazes should soak up as little oxygen as possible, you want the piece to go from the kiln to the reduction chamber as quickly as possible. This causes the glaze to have as much reduction as possible and can pull out vibrant flashes of color from the glaze and end with either a matte or glossy depending on the type of glaze that you use colorful look.

Naked Raku is done by coating a section of the exterior of the piece with the slip taping off anywhere on the piece that you want to turn black after reduction. Then you place the piece directly into the kiln and slowly heat up to about 500 °F (260 °C) until the slip has dried. Once dry continue heating until 1,400 °F (760 °C). When you reach temperature you can pull the piece from the kiln and place the piece into the reduction chamber. In reduction the carbon will soak into the clay where the slip has cracked and turn black, but where the slip is stuck on the clay will keep its natural color. Once the piece has cooled enough you can use your finger nails or a credit card to chip off the slip and reveal the design.[13]

Horse hair: Horse hair decoration is a process where the piece is left without glaze and brought up to temperature in the kiln and when removed from the kiln it is not placed into the reduction chamber; instead it is placed in the open where horse hair is strategically arranged on the piece. The horse hair will immediately burn and leave thin linear markings on the pottery.

Tea bowl with designs of pine boughs and interlocking circles, unknown raku ware workshop, Kyoto, Edo period, 18th–19th century

Tea bowl with designs of pine boughs and interlocking circles, unknown raku ware workshop, Kyoto, Edo period, 18th–19th century Raku work with crackle glazes (left) copper glazes (right) and pop-off slip (center)

Raku work with crackle glazes (left) copper glazes (right) and pop-off slip (center)

In literature

Hiroshi Teshigahara made the film "Rikyu", which is a nearly documentary story showing how Sen no Rikyu met Chojiro, who made the first genuine Raku tea bowl (chawan) and how Rikyu trained the shogun Toyotomi Hideyoshi in the tea ceremony with Raku chawans.(Ashton D 1997).

Bibliography

- Ashton D: The delicate thread. Teshigahara's life in art. Kodansha Int. Tokyo 1997;150-163.

- Pitelka, Morgan. Handmade Culture: Raku Potters, Patrons, and Tea Practitioners in Japan. University of Hawaii Press, 2005. ISBN 0-8248-2970-0.

- Hamer, Frank and Janet. The Potter's Dictionary of Materials and Techniques. A & C Black Publishers, Limited, London, England, Third Edition 1991. ISBN 0-8122-3112-0.

- Peterson, Susan. The Craft and Art of Clay. The Overlook Press, Woodstock, NY, Second Edition 1996. ISBN 0-87951-634-8.

- Watkins, James C. Alternative Kilns & Firing Techniques: Raku * Saggar * Pit * Barrel, Lark Ceramics Publications, 2007. ISBN 978-1-57990-455-5, ISBN 1-57990-455-6.

- Branfman, Steven. "Raku FAQs." Ceramics Today. Ceramics Today, Sept. 2002. Web. 6 May 2010.

- Herb, Bill. "What Is Raku." Dimensional Design. Bill Herb A.k.a Dimensional Design, Jan. 2000. Web. 6 May 2010.

- Knapp, Brian J. Oxidation and Reduction. Port Melbourne, Vic.: Heinemann Library, 1998. Print.

- Birks, Tony. The New Potter's Companion. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1982. Print.

- Rhodes, Daniel. "Special Glazes and Surface Effects." Clay and Glazes for the Potter. Revised ed. Randor: Chilton Book Company, 1973. 318. Print.

- Zamek, Jeff. "Glazes: Materials, Mixing, Testing, Firing." Ceramic Arts Daily – Featured Tip of the Day. Ceramic Publications Company, 5 Nov. 2009. Web. 26 May 2010. <http://ceramicartsdaily.org/ceramic-glaze-recipes/glaze-chemistry-ceramic-glaze-recipes-2/glazes-materials-mixing-testing-firing/?floater=99>.

- Andrews, Tim " Raku: a review of contemporary work". A.C.Black, London. 1994 ISBN 0-7136-3836-2

- Andrews, Tim " Raku". A.C.Black, London. 2nd Ed.2005 ISBN 0-7136-6490-8

- Aguirre, Amber (2012). Naked Fauxku. In Pottery Making Illustrated, Jan/Feb vol 15, p. 40-42.

References

- Byers, Ian (1990). The Complete Potter: Raku. Series Ed. Emmanuel Cooper. B.T. Batsford Ltd 1990, pp. 16. ISBN 0-7134-6130-6

- Branfman, Steven (2001). Raku: A Practical Approach. United States: krause publications. p. 17.

- "Jane Malvisi". www.janemalvisi.co.uk. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- http://www.studiopottery.com/cgi-bin/mp.cgi?item=9

- Warshaw, Josie. The Practical Potter: a Step-by-step Handbook : a Comprehensive Guide to Ceramics with Step-by-step Projects and Techniques. London: Hermes House, 2003. Print.

- http://www.koryu.com/library/wbodiford1.html

- Arbuckle. "Reduction Firing." Reduction Firing. Web. 6 May 2010. <http://lindaarbuckle.com/handouts/reduction_fire.pdf>.

- "Oxidation/Reduction Firing." Frog Pond Pottery. Web. 29 May 2010.<"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 29 May 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)>.

- source(Knapp, Brian J. Oxidation and Reduction. Port Melbourne, Vic.: Heinemann Library, 1998. Print.)

- source(Birks, Tony. The New Potter's Companion. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1982. Print.)

- Branfman

- Herb

- Riggs, Charlie. "charlie riggs pop off slip" (PDF). Lessparks.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Raku ware. |