Raden

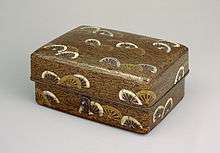

Raden (螺鈿) is a Japanese term for one of the decorative techniques used in traditional crafts such as Japanese lacquerware and woodwork. It refers to a method of inserting a board-like material, which is a cut out part of the mother of pearl inside the shell, into the carved surface of lacquer or wood, or a craft made by using this method. The kanji for ra (螺) means shell and den (鈿) means inlaid. "Raden" is a term used only for the technique or work of inlaying thin layers of pearl shells. In Japan, the technique to inlay ivory or metal is simply called "象嵌, zougan or zōgan" which means inlay.

The term may also be used for similar traditional work from Korea or countries in South-East Asia such as Vietnam, or for modern work done in the West.

Techniques of production

There are many ways that raden is produced, with all techniques classed under three main categories: Atsugai (using thick shell pieces), Usugai (using much thinner pieces), and Kenma (the thinnest application of shell pieces).

In Atsugai raden, the shell is often cut with a scroll saw, then finished with a file or rubstone before application. In Usugai raden, the thinner shell pieces are usually made using a template and a special punch. Kenma raden is fashioned similarly to Usugai raden.

Methods of application are varied. Thick shell pieces may be inlaid into pre-carved settings, while thinner pieces may be pressed into a very thick coating of lacquer, or applied using an adhesive and then lacquered over. Other methods use acid washing and lacquering to produce different effects.

Raden is especially combined with maki-e, gold or silver lacquer sprinkled with metal powder as a decoration.

History

Raden was imported to Nara period (710–794) Japan from Tang Dynasty China (618–907) and was used in mosaics and other items in combination with amber and tortoise shell. Raden developed rapidly in the Heian period (794–1185), and was used in architecture as well as lacquerware. In the Kamakura period (1185–1333), raden was a popular saddle decoration and in the Muromachi period (c. 1336–1573), highly valued Chinese raden greatly influenced the Japanese style.

Raden experienced rapid growth through Japan's Azuchi-Momoyama period (1568–1600), when Japan's borders were still open to the outside world, until the early 17th century, before the isolationism instituted by the Seclusion laws of the Edo period (1600–1867). The technique was often used in the creation of European-style items, such as chests of drawers and coffee cups, and was very popular in Europe, as the mother-of-pearl covering the items contributed to their status as a unique luxury. The Japanese referred to these goods as "Nanban lacquerware", with Nanban meaning "Southern Barbarians", a term borrowed from the Chinese and, in 16th century Japan, meaning any foreigner, especially a European.

In Japan's Edo period, raden continued in popularity despite the closing of the European market. Craftsmen necessarily focused on Japanese items. The raden works of a number of famous Edo period craftsmen are still celebrated, namely those of Tōshichi Ikushima, Chōbei Aogai, and Saiku Somada. After the Opening of Japan to foreign trade in the 1850s, raden work for export markets soon became significant again. Raden is widespread in Japan today, and is made for many applications, modern and classic.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Raden (crafts). |

Notes

- The upper tier holds inkstone and water dropper; lower tier is for paper; eight bridges design after chapter 9 of The Tales of Ise; irises and plank bridges 1700, Black lacquered wood, gold, maki-e, abalone shells, silver and corroded lead strips (bridges).