Qvist's theorem

In projective geometry Qvist's theorem, named after the Finnish mathematician Bertil Qvist, is a statement on ovals in finite projective planes. Standard examples of ovals are non-degenerate (projective) conic sections. The theorem gives an answer to the question How many tangents to an oval can pass through a point in a finite projective plane? The answer depends essentially upon the order (number of points on a line −1) of the plane.

Definition of an oval

- In a projective plane a set Ω of points is called an oval, if:

- Any line l meets Ω in at most two points, and

- For any point P ∈ Ω there exists exactly one tangent line t through P, i.e., t ∩ Ω = {P}.

When |l ∩ Ω | = 0 the line l is an exterior line (or passant),[1] if |l ∩ Ω| = 1 a tangent line and if |l ∩ Ω| = 2 the line is a secant line.

For finite planes (i.e. the set of points is finite) we have a more convenient characterization:[2]

- For a finite projective plane of order n (i.e. any line contains n + 1 points) a set Ω of points is an oval if and only if |Ω| = n + 1 and no three points are collinear (on a common line).

Statement and proof of Qvist's theorem

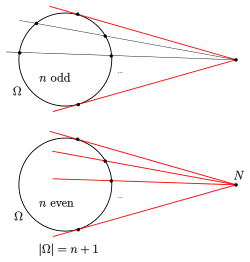

Let Ω be an oval in a finite projective plane of order n.

- (a) If n is odd,

- every point P ∉ Ω is incident with 0 or 2 tangents.

- (b) If n is even,

- there exists a point N, the nucleus or knot, such that, the set of tangents to oval Ω is the pencil of all lines through N.

- Proof

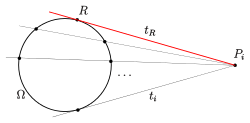

(a) Let tR be the tangent to Ω at point R and let P1, ... , Pn be the remaining points of this line. For each i, the lines through Pi partition Ω into sets of cardinality 2 or 1 or 0. Since the number |Ω| = n + 1 is even, for any point Pi, there must exist at least one more tangent through that point. The total number of tangents is n + 1, hence, there are exactly two tangents through each Pi, tR and one other. Thus, for any point P not in oval Ω, if P is on any tangent to Ω it is on exactly two tangents.

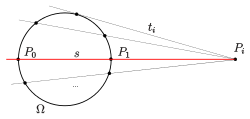

(b) Let s be a secant, s ∩ Ω = {P0, P1} and s= {P0, P1,...,Pn}. Because |Ω| = n + 1 is odd, through any Pi, i = 2,...,n, there passes at least one tangent ti. The total number of tangents is n + 1. Hence, through any point Pi for i = 2,...,n there is exactly one tangent. If N is the point of intersection of two tangents, no secant can pass through N. Because n + 1, the number of tangents, is also the number of lines through any point, any line through N is a tangent.

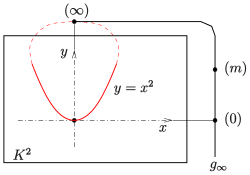

- Example in a pappian plane of even order

Using inhomogeneous coordinates over a field K, |K| = n even, the set

- Ω1 = {(x, y) | y = x2} ∪ {(∞)},

the projective closure of the parabola y = x2, is an oval with the point N = (0) as nucleus (see image), i.e., any line y = c, with c ∈ K, is a tangent.

Definition and property of hyperovals

- Any oval Ω in a finite projective plane of even order n has a nucleus N.

- The point set Ω := Ω ∪ {N} is called a hyperoval or (n + 2)-arc. (A finite oval is an (n + 1)-arc.)

One easily checks the following essential property of a hyperoval:

- For a hyperoval Ω and a point R ∈ Ω the pointset Ω \ {R} is an oval.

This property provides a simple means of constructing additional ovals from a given oval.

- Example

For a projective plane over a finite field K, |K| = n even and n > 4, the set

- Ω1 = {(x, y) | y = x2} ∪ {(∞)} is an oval (conic section) (see image),

- Ω1 = {(x, y) | y = x2} ∪ {(0), (∞)} is a hyperoval and

- Ω2 = {(x, y) | y = x2} ∪ {(0)} is another oval that is not a conic section. (Recall that a conic section is determined uniquely by 5 points.)

Notes

- In the English literature this term is usually rendered in French (or German) rather than translating it as a passing line.

- Dembowski 1968, p. 147

- Bertil Qvist: Some remarks concerning curves of the second degree in a finite plane, Helsinki (1952), Ann. Acad. Sci Fenn Nr. 134, 1–27

- Dembowski 1968, pp. 147–8

References

- Beutelspacher, Albrecht; Rosenbaum, Ute (1998), Projective Geometry / from foundations to applications, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-48364-3

- Dembowski, Peter (1968), Finite geometries, Ergebnisse der Mathematik und ihrer Grenzgebiete, Band 44, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 3-540-61786-8, MR 0233275

External links

- E. Hartmann: Planar Circle Geometries, an Introduction to Moebius-, Laguerre- and Minkowski Planes. Skript, TH Darmstadt (PDF; 891 kB), p. 40.