Quizquiz

Quizquiz or Quisquis was, along with Chalcuchimac and Rumiñawi, one of Atahualpa's leading generals. In April 1532, along with his companions, Quizquiz led the armies of Atahualpa to victory in the battles of Mullihambato, Chimborazo and Quipaipan, where he, along with Chalkuchimac defeated and captured Huáscar and promptly killed his family, seizing capital Cuzco. Quizquiz later commanded Atahualpa's troops in the battles of Vilcaconga, Cuzco (both 1533) and Maraycalla (1534), ultimately being bested by the Spanish forces in both accounts.

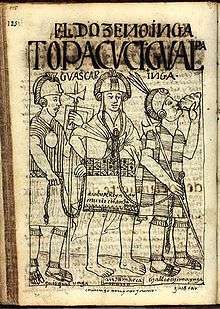

Quizquiz | |

|---|---|

Quizquiz (left), while leading Huáscar prisoner | |

| Died | 1535 |

| Nationality | Inca |

| Occupation | General |

After the ensuing battles, Quizquiz fled further into the safety of the Andean mountains, but his forces soon demanded that he accept the Spanish demands, and, it being planting season, that they be able to return to their families. Quizquiz refused, and his war-weary troops eventually killed him in 1535.

Origin of the name

Quizquiz is a Quechua term, which stands for leader or Little Bird par excellence. According to some authors instead, the surname means barber and derives from his duty to shave the King Huayna Capac that the General had exercised, both for his dexterity and for Huayna Capac's total confidence so that he would not have liked to offer his throat to anyone else.

Biography

Military triumphs

His first military experience was gained in the army of Huayna Capac, in campaigns in North, where he distinguished himself for his outstanding military skills.

On the death of the eleventh Sapa Inca, Quizquiz remained in the wake of his son Atahualpa, assuming the chief command of the armies of Quito, contrasted with those of Cuzco devoted to Huáscar.

Juan de Betanzos reports in his Narrative of the Incas that during the civil war Quizquiz led troops of 60,000 against Huáscar's troops.[1]:189

As supreme commander he organized, together with another prestigious general Chalcuchimac, war against Cuzco. Quizquiz was responsible for the significant defeat and capture of Huáscar, where Huáscar planned to use a decoy advance guard that was to be later joined by the body of the army, however this decoy was destroyed before the rest of the army could join it. Defeating in several battles the armies of Huáscar, they achieved the final victory with the storming of the Inca Empire capital.[2]:146–149 As he was proceeding to the consolidation of power for Atahualpa in the region of Cuzco, the news came of the tragedy of Cajamarca and the capture of his master.

Atahualpa then had Chalcuchimac stay with half of his warriors in Jauja, and Quizquiz with the other half in Cusco.[3]:31

Meeting with the Spanish

Quizquiz was in Cusco at the time of the Spaniards' arrival.[4] The inhabitants recognized the Spanish were not gods by their behavior. Collecting the ransom, Atahualpa had convinced Francisco Pizarro to send three soldiers in the capital to personally check on the collection of gold. The three, Martín Bueno, Pedro Martin de Moguer and Pedro de Zárate, were treated honorably, despite their far from blameless behavior. The rude soldiers ventured to desecrate the temples and undermine the Virgins of the Sun, but the instructions from Atahualpa did not allow any appropriate measures to be taken against the three.[2]:193[3]:34

Fight against invaders

Pizarro selected Túpac Huallpa as the next Inca, but soon this Inca died. Manco Inca then joined Pizarro on his march to Cusco.[3]:38,40,46

The Spaniards occupied only three locations in Peru when the armies moved from Cuzco to Quito. One was the city of Cuzco itself, the second was the town of Jauja (Sausa), entrusted to the treasurer Riquelme, and the third was the recent settlement of San Miguel which ensured the flow of reinforcements by sea. Quizquiz attacked Cusco first, but Pizarro sent Almagro and fifty men to confront the attack. The Spaniards "killed and wounded many of them." Quizquiz then decided to attack the garrison of Jauja, on the road to Quito, but was "unable to prevail against the Spaniards" there as well.[5]:327–328

The rainy season had swelled rivers and was sufficient to demolish the bridges on the most tumultuous rivers to secure the rear from the arrival of Cuzco followers. The clash ensued between the army of Quito and fifty Spanish Juaja backed by thousands of indigenous friends. Quizquiz had developed strategies that worked against the Spanish, but he still had to learn to deal with the cavalry. His men carried out a pincer movement, but the impetus of the horses swept their ranks. The day, however, was not an easy one for the Spanish troops. Riquelme was himself wounded in the head and fell into the river, where he was rescued by a group of indian archers of the Antisuyu. One Spaniard was killed and almost all other reported injuries as their auxiliary natives were decimated by the troops of Quito.

Northern troops still managed to pass Jauja, while regretting that it could not conquer the city defended by a small garrison. Quizquiz had learnt from the experience and venturing in a ravine he fortified the slopes of the passage so that horses could not work, then he remained on hold.

Reinforcements from Cuzco came upon a few weeks later, under the command of Hernando de Soto and Diego de Almagro, accompanied by many Indians, sent by Manco Inca Yupanqui, elected meanwhile supreme Inca.

Learned that Quizquiz was close, the Spaniards threw themselves boldly forward, but this time the shrewd general was not waiting for them unprepared. The defenses worked fine and their charges shattered against the properly prepared fortifications.

While worryingly studying what to do, the conquistador learned that the armies had abandoned their positions and headed north. Quizquiz, obviously, wanted to regain the region of Quito. The Spanish moved in pursuit, but proceeding with great caution and fighting only limited clashes with the marching rearguard, then, when it became clear that the enemy abandoned the region, desisted from following them.

Quizquiz had solved the immediate problem of the pursuers, but his difficulties were not over. He had to open a way through districts infested by hostile populations, related to the deceased Huáscar and hoping for a comeback thanks to the arrival of "white men" who, unwisely, were seen as liberators.

Nevertheless, by means of an impressive march led by overcoming difficulties of all kinds, not only strategic, but also and mainly logistical, Quizquiz led the several thousand men who composed his army beyond the boundaries of the ancient kingdom of Quito, where he planned to find support and allies.

Last battle

Arriving in the land of Quito to organize a brave resistance, and possibly a war of Reconquista, he had a bitter surprise to find the Spanish contingent that had preceded him, coming from San Miguel, under the leadership of Benalcazar. They were then followed by other armies commanded by Almagro and Pedro de Alvarado.

It was precisely the troops of Alvarado, who travelled the country looking for Rumiñawi and other opponents, to encounter the army of Quizquiz randomly. A detachment of them collided with a patrol of Quizquiz and their leader, Sotaurco, put to torture, was forced to reveal its location.

Convinced of holding the enemy, the Spaniards moved with incredible quickness. By forced march, travelling at night by the light of torches and stopping only for shoeing horses, they came unexpectedly in view of the marching army.

Quizquiz was obviously surprised, but as consummate strategist acted with surprising speed. Before the enemy came in contact, he had already divided his army into two parts. One, with all the warriors, was launched on the slopes of a hill and stood in defence. The other, conducted by him personally, with most provisions and women, trying to pull in another direction.

As the prudent general had foreseen, the Spaniards launched the assault of enemy warriors, but those under the command of an Atahualpa brother named Huaypalcon, kept them at bay without effort by rolling an avalanche of stones from the top.

During the night, the two Inca armies merged and the Spaniards were forced to the pursuit, but were stopped at the crossing of a river that separated the contenders. The natives even attacked by setting up a bridgehead on the bank defended by the Spanish and inflicted casualties on the enemy.

As the news came that a nearby indigenous detachment killed and beheaded fourteen Spaniards who tried to rejoin their compatriots, they decided to retire.

Quizquiz had won, but this was to be his last battle.

Death

After meeting with the men of Almagro and Alavarado, Quizquiz still took part in many fights, but soon realized that the circle of the enemy was closing in on him. Events had shown that, even if it was possible to defend themselves in some way, it was unthinkable to be able to finally defeat the powerful invader.

It requires a change in strategy and Quizquiz thought to transform the war in guerrilla. To do this they should hide in the forest and from there to make quick raids, never facing a confrontation.

The area where he wanted to lead troops, however, was wild and unexplored, and although they were guaranteed some security in case of attack, involving the certainty of suffering hunger, given the large number of men who would have been involved. Quizquiz helpers were all opposed to this decision, but the stubborn general, stressed and angry for their resistance, charged them of cowardice.

According to Pedro Cieza de Leon, "Quizquiz went with the Huambracuna back to Quito, without having accomplished anything that he had intended. He had been praised for being a very brave and wise captain and of good judgment. The very Huambracuna who went with him killed him near Quito in the village of Tiamcambe." His warriors wanted peace so they could return home, but he refused. "Huaypalcon attacked him, and others joined in with battle axes and clubs and killed him." [5]:328–329

"Thus fell the last of the two great officers of Atahualpa."[2]:223

See also

References

- Betanzos, J., 1996, Narrative of the Incas, Austin: University of Texas Press, ISBN 0292755600

- Prescott, W.H., 2011, The History of the Conquest of Peru, Digireads.com Publishing, ISBN 9781420941142

- Pizzaro, P., 1571, Relation of the Discovery and Conquest of the Kingdoms of Peru, Vol. 1-2, New York: Cortes Society, RareBooksClub.com, ISBN 9781235937859

- Andagoya, Pascual de. "Narrative of the Proceedings of Pedrarias Davila". The Hakluyt Society. Retrieved 21 June 2019 – via Wikisource.

- Leon, P., 1998, The Discovery and Conquest of Peru, Chronicles of the New World Encounter, edited and translated by Cook and Cook, Durham: Duke University Press, ISBN 9780822321460

Eyewitnesses of early wins

- Miguel de Estete

- Relación the viaje ... desde el pueblo de Caxmalca a Pachacamac. (1533) In Ramusio Einaudi, Torino 1988

- Noticia del Perú (1540) In COL. LIBR. DOC. HIST. PERU (2 nd series Volume 8 °, Lima 1920)

- Francisco de Jerez Verdadera relación de la conquista del Perú (1534) In Ramusio Einaudi, Torino 1988

- Pedro Pizarro Relación del descubrimiento y conquista de los Reynos del Perú. (1571) in BIBL. AUT. ESP. (Volume CLVIII, Madrid 1968)

- Pedro Sancho de Hoz Relatione di quel che nel conquisto & pacificatione di queste provincie & successo...& la prigione del cacique Atabalipa. (1534) In Ramusio Einaudi, Torino 1988

Other historians

- Pedro Cieza de León

- Segunda parte de la crónica del Perú (1551) In COL. CRONICA DE AMERICA (Dastin V. 6°. Madrid 2000)

- Descubrimiento y conquista del Perú (1551) in COL. CRONICA DE AMERICA (Dastin V. 18°. Madrid 2001)

- Bernabé Cobo Historia del Nuevo Mundo (1653) In BIBL. AUT. ESP. Tomi XCI, XCII, Madrid 1956

- Garcilaso de la Vega

- Commentarios reales (1609) Rusconi, Milano 1977

- La conquista del Peru (1617) BUR, Milano 2001

- Francisco López de Gómara Historia general de las Indias (1552) In BIBL. AUT. ESP. (tomo LXII, Madrid 1946)

- Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés Historia General y natural de las Indias 5 Vol. in IBL. AUT. ESP. (tomi CXLVI - CLI), (Madrid 1991)

- Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas Historia general ... (1601–1615) COL. Classicos Tavera (su CD)

- Titu Cusi Yupanqui Relación de la conquista del Perú y echos del Inca Manco II (1570) In ATLAS, Madrid 1988