Pythium irregulare

Pythium irregulare is a soil borne oomycete plant pathogen.[1] Oomycetes, also known as "water molds", are fungal-like protists. They are fungal-like because of their similar life cycles, but differ in that the resting stage is diploid, they have coenocytic hyphae, a larger genome, cellulose in their cell walls instead of chitin, and contain zoospores (asexual motile spores) and oospores (sexual resting spores).[2]

| Pythium irregulare | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Chromista |

| Phylum: | Oomycota |

| Order: | Peronosporales |

| Family: | Pythiaceae |

| Genus: | Pythium |

| Species: | P. irregulare |

| Binomial name | |

| Pythium irregulare Buisman, (1927) | |

Hosts and symptoms

Pythium irregulare is an oomycete that causes pre- and post-emergence damping off, as well as root rot.[1] Pre-emergence damping off occurs when P. irregulare infects seeds before they emerge, causing them to rot and turn brown, thus preventing successful growth.[1][3] Alternatively, post-emergence damping off occurs when the oomycete infects just after the seed has germinated.[1][3] This usually causes infection in the roots and stem which appears as water soaking and necrosis.[1][3] Depending on the severity, plants may collapse or be severely stunted.[1] In plants that are older and more established, P. irregulare causes root rot.[3] This will initially cause necrotic lesions, which leads to chlorosis, reduced yield, poor growth, and stunting due to inadequate water and nutrient acquisition by the roots.[1] Additionally, P. irregulare is often found coinfecting with other Pythium species.[1] All three of these diseases caused by P. irregulare can be caused by other pathogens as well, so a disease diagnosis is not necessarily indicative of P. irregulare[4]

In order to identify Pythium irregulare it is necessary to isolate the organism and observe it microscopically. First, it is important to identify that the microbe is an oomycete by looking for characteristics that are specific to oomycetes, such as coenocytic hyphae, zoospores, and oospores.[2] After that, one can identify the microbe as being in the genera Pythium by observing disease symptoms, host range, as well as the presence of a vesicle, where zoospores form, which is attached to the sporangia.[5] In contrast, most other oomycetes do not have a vesicle and the zoospores form in the sporangia.[5] Finally, once the genera has been identified, it is helpful to use a dichotomous key to identify the species.[6] Some of the key identifiers for P. irregulare include oogonia with irregular shaped, cylindrical projections, sporangia that occur singly, sporangia that are not filamentous, and oogonia smaller than 30 μm.[7] There are also many genomic tests that can be done to determine species based on specific DNA markers.[8] It is also important to note that many diagnosticians do not identify to the species level because it can be difficult to find all necessary microscopic structures and many management techniques can be applied to all Pythium species.[8][9]

Pythium irregulare has a very broad host range, including many agronomically and horticulturally important crops and is found on every continent except for Antarctica.[1] P. irregulare infects over 200 species, including cereals, legumes, fruits, vegetables, and ornamentals.[1] It differs from many other Pythium species in that it prefers cooler environments.[1][3] A moist environment is also necessary for disease, which aids motility of spores.[1][3] It is commonly found in both greenhouses and fields.[1][4][9]

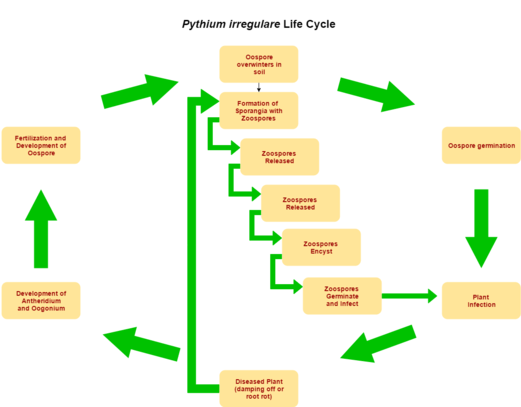

Disease cycle

Pythium irregulare, like most oomycetes, has a life cycle with sexual and asexual stages.[1] During the winter, oospores, which are sexual resting spores, survive in the soil.[1][9] Oospore germination occurs when the oospore senses chemicals released by seeds or roots.[1] Once germinated, oospores can produce either a germ tube, which directly infects the plant, or a sporangium, which releases zoospores that infect the plant.[1][9] Sporangium that produce zoospores make up the asexual phase of the life cycle. The zoospores can move through soil when water is present, which is why water is important for disease to occur.[1] Once zoospores reach the root or seed, they encyst, germinate, and infect via a germ tube.[1][9] Once infection has been established, the pathogen grows hyphae both in and outside the plant and releases enzymes to breakdown plant tissue.[1][9] The breakdown of tissue provides nutrients for the pathogen, also known as necrotrophy.[9] Once the plant dies, more sporangium can form, release zoospores, and repeat the infection cycle.[9] Alternatively, the hyphae within the dead plant material may also continue to grow and develop “male” and “female” haploid mating structures, known as antheridium and oogonium, respectively.[1] The antheridium then transfers its genetic material to the oogonium (fertilization), resulting in the diploid oospore, which overwinters and starts the infection over again in the spring.[1]

Management

Pythium irregulare requires very specific environmental conditions to produce disease, so control of environment is the first step.[10] Because the zoospores require water to be able to move around, preventing standing water will decrease the chance of disease occurrence.[10] Additionally, excess water can lead to an increase in insects that feed on roots, making it easier for the pathogen to spread, as it can make its way into the plant through wounds.[9] Water levels can be controlled by avoiding planting in areas that have poor drainage and controlling irrigation as to not overwater plants.[9][10] Because P. irregulare has oospores that survive under harsh conditions, sanitation is very important to limit the spread.[9][10] Contaminated irrigation systems, tools, and seeds can spread the disease, so disinfection with heat or chemicals are necessary to prevent further spread, as well as purchasing certified clean seed.[4][9][10][11] Additionally, in greenhouses scenarios it is important to sanitize soil, work benches, and tools with heat or chemicals as well.[4][9][10] It is also important to avoid over-fertilizing plants, as fertilizers can suppress plant defenses and damage roots, making it easier for P. irregulare to infect.[9] Finally, if you have had previous problems with Pythium irregulare, you can take preventative measures by mixing fungicides into the soil, although this is more easily achieved in a greenhouse scenario.[9][10] It is important to create a fungicide plan with different rotations of fungicides if you choose to prevent disease this way in order to prevent the pathogen from becoming resistant to the fungicide.[9] Some fungicides used to prevent P. irregulare include mefenoxam, fosetyl-Al, and etridiazole.[9][10] Additionally, certain biological agents such as Trichoderma harzianum and Gliocladium virens can be used as biological control measures to prevent infection; however, this is also a more plausible control method in a greenhouse, again because it needs to be mixed into the soil.[10] Crop rotation is not necessarily a good option for P. irregulare control because many crops are viable hosts, oospores can survive in the soil for many years, and the pathogen can survive on organic matter; however, rotation with a non-host crop may be able to reduce the pathogen load, thus decreasing infection in subsequent years[12]

See also

References

- Katawczik, Melanie. "Pythium irregulare". projects.ncsu.edu. North Carolina State University, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Department of Plant Pathology. Retrieved 2016-12-06.

- Judelson, Howard S.; Blanco, Flavio A. (2005-01-01). "The spores of Phytophthora: weapons of the plant destroyer". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 3 (1): 47–58. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1064. ISSN 1740-1526. PMID 15608699.

- Moorman, Gary; May, Sara. "Disease Caused by Pythium". http://plantpath.psu.edu/pythium/. Penn State, College of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Plant Pathology and Environmental Microbiology. Retrieved 2016-12-06. External link in

|website=(help) - "Pythium". http://extension.psu.edu/pests/plant-diseases/all-fact-sheets/pythium. Penn State College of Agricultural Sciences Extension. Retrieved 2016-12-06. External link in

|website=(help) - Heffer Link, Virginia; Powelson, Mary; Johnson, Kenneth. "Oomycetes". The American Phytopathological Society. Archived from the original on 2016-11-22. Retrieved 2016-12-06.

- http://plantpath.psu.edu/pythium/module-3/plaats-niterink-key-pythium

- Plaats-Niterink, A.J. van der. "Key to the Species of Pythium". Penn State University. Retrieved 2016-12-06.

- "Pythium Genome Database". Michigan State University. Retrieved 2016-12-06.

- Beckerman, Janna. "Pythium Root Rot of Herbaceous Plants" (PDF). Disease Management Strategies for Horticultural Crops. Purdue Agricultural Communication. Retrieved 2016-12-05.

- "Pythium Root Rot". University of California Pest Management Guidelines. University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources. Retrieved 2016-12-06.

- "Disease Alert: Pythium". Syngenta. Retrieved 2016-12-05.

- McGrath, Margaret. "Managing Plant Diseases With Crop Rotation". www.sare.org. Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education. Retrieved 2016-12-06.