Pythagorean astronomical system

An astronomical system positing that the Earth, Moon, Sun and planets revolve around an unseen "Central Fire" was developed in the 5th century BC and has been attributed to the Pythagorean philosopher Philolaus.[1][2] The system has been called "the first coherent system in which celestial bodies move in circles",[3] anticipating Copernicus in moving "the earth from the center of the cosmos [and] making it a planet".[4] Although its concepts of a Central Fire distinct from the Sun, and a nonexistent "Counter-Earth" were erroneous, the system contained the insight that "the apparent motion of the heavenly bodies" was (in large part) due to "the real motion of the observer".[5] How much of the system was intended to explain observed phenomena and how much was based on myth and religion is disputed.[4][5] While the departure from traditional reasoning is impressive, other than the inclusion of the 5 visible planets, very little of the Pythagorean system is based on genuine observation. In retrospect, Philolaus's views are "less like scientific astronomy than like symbolical speculation."[6]

Before Philolaus

Contributions to Pythagorean astronomy before Philolaus are limited. Hippasus, another early Pythagorean philosopher, did not contribute to astronomy, and no evidence of Pythagoras's work on astronomy remains. All remaining astronomical contributions are unable to be attributed to a single person and therefore Pythagoreans as whole take the credit. However, it should not be assumed that the Pythagoreans as a unanimous mass agreed on a single system at this point in time.[8]

One surviving theory from the Pythagoreans before Philolaus, the harmony of the spheres, is first mentioned in Plato’s Republic. Plato presents the theory in a mythological sense by including it in the legend of Er, which concludes the Republic. Aristotle mentions the theory in De Caelo, in which he presents the theory as a "physical doctrine" that coincides with the rest of the Pythagorean cosmology, rather than attributing it to myth.[8]

Zhmud summarizes the theory thus:

1) the circular motion of the celestial bodies produces a sound; 2) the loudness of the sound is proportional to their speed and magnitude (according to Achytas, the loudness and pitch of the sound depends on the force with which it is produced; 3) the velocities of the celestial bodies, being proportional to their distances from the earth, have the ratios of concords; 4) hence the planets and stars produce harmonious sounds; 5) we cannot hear this harmonious sound.

— Zhmudʹ, L. I͡a. Pythagoras and the Early Pythagoreans. p. 340.

Philolaus

Philolaus (c. 470 to c. 385 BC) was a follower of the pre-Socratic Greek philosopher Pythagoras of Samos. Pythagoras developed a school of philosophy that was both dominated by mathematics and "profoundly mystical".[3] Philolaus himself has been called one of "the three most prominent figures in the Pythagorean tradition"[4] and "the outstanding figure in the Pythagorean school", who may have been the first "to commit Pythagorean doctrine to writing".[5] Most of what is known today about the Pythagorean astronomical system is derived from Philolaus's views.[8] Because of questions about the reliability of ancient non-primary documents, scholars are not absolutely certain that Philolaus developed the astronomical system based on the Central Fire, but they do believe that either he, or someone else in the late 5th century BC, created it.[5] Another issue with attributing the whole of Pythagorean astronomy to Philolaus is that he may have had non-Pythagorean teachers.[8]

The system

In the Pythagorean view, the universe is an ordered unit. Beginning from the middle, the universe expands outward around a central point, implying a spherical nature. In Philolaus’s view, for the universe to be formed, the "limiters" and "unlimited" must harmonize and be fitted together. Unlimited units are defined as continuous elements, such as water, air, or fire. Limiters, such as shapes and forms, are defined as things that set limits in a continuum. Philolaus believed that universal harmony was achieved in the Central Fire, where the combination of an unlimited unit, fire, and the central limit formed the cosmos.[9][10] It is assumed as such because fire is the "most precious" of elements, and the center is a place of honor. Therefore, there must be fire at the center of the cosmos.[6] According to Philolaus, the central fire and cosmos are surrounded by an unlimited expanse. Three unlimited elements: time, breath, and void, were drawn in toward the central fire, where the interaction between fire and breath created the elements of earth and water. Additionally, Philolaus reasoned that separated pieces of the Central Fire may have created the heavenly bodies.[9]

These heavenly bodies, namely the earth and planets, revolved around a central point in Philolaus's system, his could not be called a Heliocentric "solar system", because the central point which the earth and planets revolved around was not the sun, but the so-called Central Fire. This Fire was not visible from the surface of Earth—or at least not from the hemisphere Greece was located in.

Philolaus says that there is fire in the middle at the centre ... and again more fire at the highest point and surrounding everything. By nature the middle is first, and around it dance ten divine bodies—the sky, the planets, then the sun, next the moon, next the earth, next the counterearth, and after all of them the fire of the hearth which holds position at the centre. The highest part of the surrounding, where the elements are found in their purity, he calls Olympus; the regions beneath the orbit of Olympus, where are the five planets with the sun and the moon, he calls the world; the part under them, being beneath the moon and around the earth, in which are found generation and change, he calls the sky.

However, it has been pointed out that Stobaeus betrays a tendency to confound the dogmas of the early Ionian philosophers, and occasionally mixes up Platonism with Pythagoreanism.[1]

According to Eudemus, a pupil of Aristotle, the early Pythagoreans were the first to find the order of the planets visible to the naked eye. While Eudemus doesn’t provide the order, it is assumed to be moon – sun – Venus – Mercury – Mars – Jupiter – Saturn – celestial sphere, based on the "correct" order accepted in the time of Eudemus. It is likely that the Pythagoreans mentioned by Eudemus predate Philolaus. [13]

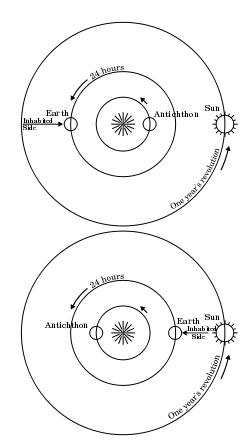

In this system the revolution of the earth around fire "at the centre" or "the fire of the hearth" (Central Fire) was not yearly but daily, while the moon's revolution was monthly, and the sun's yearly. It was the earth's speedy travel past the slower moving sun that resulted in the appearance on earth of the sun rising and setting. Further from the Central Fire, the planets' revolution was slower still and the outermost "sky" (i.e. stars) probably fixed.[4]

Central Fire

The Central Fire defines the center-most limit in the Pythagorean astronomical system. It is around this point that all heavenly bodies were said to rotate. Wrongly translated as Dios phylakê or "Prison of Zeus", a sort of hell,[4] the Central Fire was more appropriately called "Watch-tower of Zeus" (Διος πυργος) or "Hearth-altar of the universe" (εστια του παντος).[14] Maniatis claims that these translations more accurately reflect Philolaus's thoughts on the Central Fire. Its comparison to a hearth, the "religious center of the house and the state," shows its proper role as "the palace where Zeus guarded his sacred fire in the center of the cosmos".[9]

Rather than there being two separate fiery heavenly bodies in this system, Philolaus may have believed that the Sun was a mirror, reflecting the heat and light of the Central Fire.[15] The 16th–17th century European thinker Johannes Kepler believed that Philolaus's Central Fire was the sun, but that the Pythagoreans felt the need to hide that teaching from non-believers.[16]

Earth

In Philolaus's system, the earth rotated exactly once per orbit, with one hemisphere (presumed to be the unknown side of the Earth) always facing the Central Fire. The Counter-Earth and the Central Fire were thus never visible from the hemisphere where Greece was located.[17] There is "no explicit statement about the shape of the earth in Philolaus' system",[18] so that he may have believed either that the earth was flat or that it was round and orbited the Central Fire as the Moon orbits Earth—always with one hemisphere facing the Fire and one facing away.[4] A flat Earth facing away from the Central Fire would be consistent with the pre-gravity concept that if all things must fall towards the center of the universe, this force would allow the earth to revolve around the center without spilling everything on the surface into space.[5] Others maintain that by 500 BC most contemporary Greek philosophers considered the Earth to be spherical.[19]

Counter-Earth

The "mysterious"[4] Counter-Earth (Antichthon) was the other celestial body not visible from Earth. We know that Aristotle described it as "another Earth", from which Greek scholar George Burch infers that it must be similar in size, shape and constitution to Earth.[20] According to Aristotle—a critic of the Pythagoreans—the function of the Counter-Earth was to explain "eclipses of the moon and their frequency",[21] and/or "to raise the number of heavenly bodies around the Central Fire from nine to ten, which the Pythagoreans regarded as the perfect number".[5][22][23]

Some, such as astronomer John Louis Emil Dreyer, think the Counter-Earth followed an orbit so that it was always located between Earth and Central Fire,[24] but Burch argues it must have been thought to orbit on the other side of the Fire from Earth. Since "counter" means "opposite", and opposite can only be in respect to the Central Fire, the Counter-Earth must be orbiting 180 degrees from Earth.[25] Burch also argues that Aristotle was simply having a joke "at the expense of Pythagorean number theory" and that the true function of the Counter-Earth was to balance Earth.[5] Balance was needed because without a counter there would be only one dense, massive object in the system—Earth. The universe would be "lopsided and asymmetric—a notion repugnant to any Greek, and doubly so to a Pythagorean",[26] because Ancient Greeks believed all other celestial objects were composed of a fiery or ethereal matter having little or no density.[5]

Later developments

In the 1st century A.D., after the idea of a spherical Earth gained more general acceptance, Pomponius Mela, a Latin cosmographer, developed an updated version of the idea, wherein a spherical Earth must have a more or less balanced distribution of land and water. Mela drew the first map on which the mysterious continent of Earth appears in the unknown half of Earth—our antipodes. This continent he inscribed with the name Antichthones.[27]

See also

- Counter-Earth

- Greek astronomy

- Pythagoreanism

- Cosmology § Historical cosmologies

References

-

- E. Cobham Brewer (1894). Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (PDF). p. 1233.

- "The Pythagoreans". University of California Riverside. Archived from the original on 2018-07-06. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- Philolaus, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Carl Huffman.

- Burch, George Bosworth. The Counter-Earth. Osirus, vol. 11. Saint Catherines Press, 1954. p. 267-294

- Kahn, C. (2001). Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans : A brief history / Charles H. Kahn. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Pub.

- Source: Dante and the Early Astronomers by M. A. Orr, 1913.

- Zhmudʹ, L. I͡a., Windle, Kevin, and Ireland, Rosh. Pythagoras and the Early Pythagoreans; Translated from Russian by Kevin Windle and Rosh Ireland. 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Maniatis, Y. (2009). Pythagorean Philolaus’ Pyrocentric Universe. SCHOLE, 3(2), 402.

- Stace, W. T. A Critical History of Greek Philosophy. London: Macmillan and, Limited, 1920 p. 38

- Early Greek Philosophy By Jonathan Barnes, Penguin

- Butler, William Archer (1879). Lectures on the History of Ancient Philosophy, Volume 1. e-book. p. 28.

- Zhmudʹ, L. I͡a., Windle, Kevin, and Ireland, Rosh. Pythagoras and the Early Pythagoreans; Translated from Russian by Kevin Windle and Rosh Ireland. 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. p. 336

- Butler, William Archer (1879). Lectures on the History of Ancient Philosophy, Volume 1. e-book. p. 28.

- "Philolaus". Sep 15, 2003. Stanford Encyclopedia or Philosophy. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

Philolaus appears to have believed that there was also fire at the periphery of the cosmic sphere and that the sun was a glass-like body which transmitted the light and heat of this fire to the earth, an account of the sun which shows connections to Empedocles

- Johannes Kepler (1618–21), Epitome of Copernican Astronomy, Book IV, Part 1.2,

most sects purposely hid[e] their teachings

- "Philolaus". Sep 15, 2003. Stanford Encyclopedia or Philosophy. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- Burch 1954: 272–273, quoted in Philolaus, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Harley, John Brian; Woodward, David (1987). The History of Cartography: Cartography in prehistoric, ancient, and medieval Europe and the Mediterranean. 1. Humana Press. pp. 136–146.

- Burch, 1954, p.285

- Heath, Thomas (1981). A History of Greek Mathematics, Volume 1. Dover. p. 165. ISBN 9780486240732.

- Arist., Metaph. 986a8–12. quoted in Philolaus, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Carl Huffman.

- "Greek cosmology, The Pythagoreans". University of California, Riverside. Archived from the original on 2018-07-06. Retrieved 2013-10-24.

The importance of pure numbers is central to the Pythagorean view of the world. A point was associated with 1, a line with 2 a surface with 3 and a solid with 4. Their sum, 10, was sacred and omnipotent.

- Dreyer, John Louis Emil (1906). History of the planetary systems from Thales to Kepler. University press. p. 42.

To complete the number ten, Philolaus created the antichthon, or counter-earth. This tenth planet is always invisible to us, because it is between us and the central fire and always keeps pace with the earth.

- Burch, 1954, p.280

- Burch, 1954, p.286-7

- Pomponius Mela. de Chorographia.