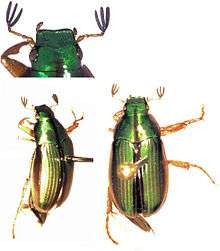

Pyronota festiva

Pyronota festiva, commonly known as manuka beetle or manuka chafer (sometimes the Maori-language spelling "mānuka" is used), is a member of the genus Pyronota of the beetle family Scarabaeidae (order Coleoptera). It is a scarab beetle endemic to New Zealand, and is commonly found in manuka trees (Leptospermum scoparium), hence the beetle's name. In some areas it is considered a pasture pest.[1]

| Pyronota festiva | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pyronota festiva male | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Coleoptera |

| Family: | Scarabaeidae |

| Genus: | Pyronota |

| Species: | P. festiva |

| Binomial name | |

| Pyronota festiva (Fabricius, 1775) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Description

The manuka beetle is bright green with shades of blue and yellow on areas of its back. Its dark longitudinal stripe down the back of its hard wing case is often brown or yellow. It can vary in length between 3 and 25mm in length, but the most common is 9mm. They are a part of the superfamily Scarabaeoidea and are characterized for their modified prothorax and have a large coxae. Their antennae is a lamellate antennal club and has a head with anterior margins which are either semicircular or emerginate mesocoxae, strongly oblique.

The manuka beetle is a part of the subfamily Melolonthinaes, which is characterized by its stout body and glossy exterior, and the presence of either labrums or mandibles. These appear as segments either elongated or as oval lobes which can be folded together tightly to form compact and asymmetrical clubs. The elbow clubs have between 8 and 10 segments. They have spindly legs covered in light coloured hairs which are strongly modified for digging with their teeth, spines and/or bristles. Their abdomens have 6 ventrites and the hind wing has a spring mechanism which can fold.

As larvae, the grub forms as a C-shape.[2]

Distribution

The manuka beetle is endemic to New Zealand. There is no compelling evidence to suggest that it is found elsewhere in the world. It is, however, closely related to other beetles in the family Scarabaeidae, like chafers, dung-beetles, and grass grubs, which are found throughout other parts of the world. An old journal article at a museum in London records the presence of manuka beetles in sheep's wool imported from New Zealand.[3]

Natural global range

The manuka beetle has a generally widespread range across New Zealand but little information has been found on the effects it has on the land outside of New Zealand. The endemic species found in New Zealand have been closely related to those of Australia, so it can be assumed that they would present there also.[4]

New Zealand range

The manuka beetle is very common, and is found in large numbers throughout New Zealand.[5] It lives in grass and vegetation habitats, which is the majority of the landscape of New Zealand. It is so common that it has become a ‘pasture pest’ to agricultural grasslands.[6]

Manuka beetles have been recorded in the North Island of New Zealand, in Egmont National Park, Taranaki. They were found present in pastures close to native bush with manuka trees. A 5 km belt around the park is evidence of the impact of manuka beetle larvae feeding on the roots of plants. Flight activities of the beetles were recorded in traps placed 50m and 20m away from manuka bush. The research showed that they were present away from the traps rather than near the bush itself.[7]

Habitat preferences

Manuka beetles have the widest ecological tolerance for different habitats out of the Melolonthidae subfamily, though they prefer woody vegetation. They tend to occur in tussock and pastures 2 to 3 years through development and been converted from native vegetation or bush regrowth.[8] However, as its common name suggests, it preferably lives in and around the soil of manuka trees (Leptospermum). Adult beetles have been seen swarming over the small white flowers that cover the manuka when it is flowering during the summer.[5]

Life cycle/phenology

Otago has been a major region for experimentation on the Pyronota species. In Macraes Flat, Otago, Stewart (1987) found that a species of Pyronota beetle followed roughly a two-year life cycle where they would span across two winters as larvae and eventually mature into adult beetles over the following summer - November through to January. As evident through general observation and their preference in habitat, it is clear that warmer temperatures draw the beetle to a specific area. As a result, this significantly increases populations; Stewart (1987) observed that adults became more active when the sun is shining as opposed to overcast days or during the night. This is interesting considering the amount of sunless days that Otago has, compared to Taranaki.

The two-year life cycle includes a three-step larval stage. Eggs were found in January where they "…spent their first winter as 1st or 2nd instar larvae and their second winter as 3rd instars." They are given a better chance of enduring their complete life cycle over two years where the conditions meet most of their need. When this isn't the case, they can develop over a shorter time period - sometimes within one year.[6] During the immature larval stage the species is said to be a minor pest. The larvae then hatch and form as pupae, eating the roots of plants which dominate the pasture soils.[9] As they grow they develop as a C shape. During the third stage they emerge from the tunnels or cracks in the soil during early summer as full-grown beetles to feed on the foliage of manuka plants. This third stage is where the damage caused by the pupae eating the roots of the plants becomes evident over autumn and winter.

Adult beetles are present a few weeks during late spring and early summer once a year. They fly in warm conditions during the day. Females lay their eggs in pasture soils at depths of up to 10 cm. Each female can lay up to 30 or 40 eggs at one time. When numbers reach 350/m2 in one period they begin to form significant damage to the pasture, which is noticeable in the form of yellow, dried-out patches of grass.[6]

The manuka beetle's life cycle is slightly different from those of its relatives, which include other members of the family Scarabaeidae: chafers, dung-beetles and grass grub beetles. Its eggs are laid in the soil, and after hatching into larvae, they have a reasonably lengthy development underground. The adult beetles die a very short time after mating, and their bodies often form drifts or mounds in and around mud or tree roots.[5]

Diet and foraging

The larvae feed on the roots of the manuka tree, providing the eggs were laid in the soil around a manuka tree. Larvae not in this situation have also been known to feed on matagouri roots and the roots of sweet briar roses. In 70% of cases, larvae were found feeding in the first 4 cm of soil, directly below the ‘turf mat'.

Adult beetles feed on the vegetation of the manuka tree. They also feed on grass roots in agricultural areas, which is the reason they are such a pest to agriculture, as they harm the grass that dairy cows eat.[10]

Manuka beetles have been studied and examined a lot in the Taranaki region. However, there are low numbers of adult beetles here because of their preference of food. They are not succeeding as well as possible in the Taranaki region because of their low counts of Leptospermum species existing both in present and past times. When manuka plant species are not in abundance, manuka beetles are being forced to feed on "matagouri (Discaria toumatou), sweet briar (Rosa rubiginosa), and Leptospermum spp." [6]

Predators, parasites, and diseases

The green colouring of the adults, and the fact they are diurnal (active during the day), means they are safe from predators because they blend in with the vegetation on which they live.[5] Predators include mice, gulls and house sparrows.

A survey done on Mokoi Island, Lake Rotorua observed house mice, Mus musculus, and what insects they were eating. Pitfall traps proved that Pyronota festiva were present throughout the island and suggested that house mice were relying on manuka beetles as one of their main food sources.[11]

Red-billed gulls have also been observed flying over farmland at Opoutere, Coromandel Peninsula from sunset, as the light is fading, and consuming small manuka beetles. This was often seen during autumn and winter, when the beetles are less likely to fly and are more vulnerable to predators as they surface from wet pastures due to an increase in rain levels.[12]

House sparrows were mapped to be eating at least three manuka beetles over a period of one to five days, when their chicks are hatching.[13] They are also a trout food.[14]

However, the beetles are pests, so there are a number of journal articles devoted to researching how to control them by targeting them with bacteria and fungi parasites, so called ‘bio-control’ methods.

Rickettsiella bacteria are being researched as a potential bio-control agent to manage the large numbers of the beetles affecting agricultural areas all over New Zealand. This bacterium is said to produce an ‘intracellular infection’ in the beetles, and many other members of their genus.[10]

As well as this bacterium, the fungus Beauveria brongniartii is being tested to help Cape Foulwind dairy farmers attack the pest. It is achieving relatively high rates of mortality in the larvae stage of the beetles. The fungal infection affects only an isolated selection of ‘scarab’ beetles, which means that it might, but is unlikely to spread onto other harmless beetles (depending on what they are).[15]

Cultural uses

There are several records of the manuka beetle being used by the indigenous Maori tribes all over New Zealand. The piles of dead adult beetle bodies that form in and around shallow water, mud and vegetation, were often collected and eaten by Maori as a delicacy.[5] Another report states that when the Maori tribes settled in New Zealand, manuka beetles were among the insects that they occasionally ate. Other uses by Maori include the beetle's antiseptic qualities and ability to reduce fevers and stomachaches. More fleshy insects like the larvae of the cerambycid beetle, or ‘huhu grub’ (as well as the adult beetle) were more widely eaten. Manuka beetles (and Puriri moths) were also used for medicinal purposes.[16]

New Zealand Fishing (1998) discusses how manuka beetles are more active during hours of daylight in November/December and can be seen lying on the surface of the water as a result of heavy winds. The trout wait in the water for the beetles to land. The presence of manuka beetles in the intestines of trout in Lake Tikitapu provides evidence of their interaction.[17]

Fishermen have also created a manuka beetle trout fly, otherwise known as the 'green beetle'. It looks similar to a green manuka beetle and is designed specifically to catch trout during the summer months.[18]

Interesting facts

Apart from the severe damage to the farmland, Pyronota festiva has been associated with major damage in the fruit trees of peaches and nectarines.[19] They have vast effects - with the aid of damage done by other insects - on the leaf and the fruit itself. Research has generally only associated the species with native grass and farmlands, so it is interesting that their scope of damage is actually quite broad.

Full-grown beetles feed on manuka plants, which have an oil compound which makes their exterior cases incredibly hard. They also contain chiral material in their hard exterior cases. When placed under a microscope with light, complexities are revealed in these multilayered chiral coatings, creating green, metallic-like reflections.

The manuka beetle can be successfully controlled through the idea of 'hoof and tooth'. Heavily stocking a pasture block during winter when the soil is very moist will cause the beetle larvae to be crushed by stock treading. This will cause the beetle's numbers to be reduced dramatically.

References

- Stewart, K. M. (1987-01-01). "Preliminary observations on the biology of a manuka chafer, Pyronota sp. (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) in Otago". New Zealand Entomologist. 9 (1): 60–63. doi:10.1080/00779962.1987.9722495. ISSN 0077-9962.

- Klimaszewski, J. (1997). "Fauna of New Zealand: Ko te Aitanga Pepeke o Aotearoa". Auckland, New Zealand: Manaaki Whenua Press. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Fabricius, J. (1775). Systema Entomologiae, sistens, insectorum classes, ordines, genera, species, adiectis synonymis, locis, descriptionibus, observationibus. Leipzig, Germany: Hafnia: Impensis Chris, Gottl, Profit.

- Hutton, F.W. (1874). "On the Geographical relations of the New Zealand fauna". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 13 (73): 25–39. doi:10.1080/00222937408562426.

- Lindsey, T.; Morris, R. (2000). Field Guide to New Zealand Wildlife.

- Stewart, K. (1987). "Preliminary observations on the biology of a Manuka chafer, Pyronota sp. (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) in Otago". New Zealand Entomologist. 9: 60–63. doi:10.1080/00779962.1987.9722495.

- Thomson, N.; Miln, A.; Kain, W. (1979). "Biology of manuka beetle in Taranaki". Taranaki Agricultural Research Station. 32: 80–8.

- "Manuka Beetle Management Brochure" (PDF). agresearch. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

- Pestweb, 2015

- Kleespies, R.; Marshall, S. (2011). "Genetic & electron microscope characterisation of Rickettsiella Bacteria from the Manuka Beetle, Pyronota setosa (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae". Invertebrate Pathology. 107 (3): 206–211. doi:10.1016/j.jip.2011.05.017. PMID 21640120.

- "List of Invertebrates on Mokoia Island, Lake Rotorua" (PDF). Department of Conservation.

- Bell, D. (2008). "Mutualistic and opportunistic foraging by red-billed gull (Larus novaehollandiae) around Hooker's sea lion (Phocartis hookeri)" (PDF). Notornis. 55: 224–225.

- Department of Conservation, 2001

- Manson, D. C. M. (1960). Native beetles of New Zealand. Wellington: A. H. & A. W. Reed. p. 38.

- Townsend, R.; Nelson, T. (2010). "Beauveria brongniartii – Potential biocontrol agent for use against Manuka Beetle larvae damaging dairy pastures on Cape Foulwind". New Zealand Plant Protection. 63: 224–228. doi:10.30843/nzpp.2010.63.6572.

- Meyer-Rochow, V.; Changkija, S. (1997). "Uses of Insects as Human Food in Papua New Guinea, Australia, and North-East India: Cross-Cultural considerations and cautious conclusions". Ecology of Food and Nutrition. 36 (2–4): 159–185. doi:10.1080/03670244.1997.9991513.

- Trout Stream insects of New Zealand; how to imitate and use them. Marsh. 2004-11-16. ISBN 9780811701303. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

- New Zealand Fishing, 1998

- Kemp, W. (1971). "Growing Peaches and Nectarines: Insect Pests". New Zealand Journal of Agriculture. 123: 77–79.