Pupuk

Pupuk is the name given to a magical substance which was used by the Batak shamans of North Sumatra. The pupuk is the main feature to perform black magic, e.g. to inflict damage to enemies. Method of creating the pupuk is inscribed in the pustaha, the magic book of the Toba people, among which involved the kidnapping and murder of a child from neighboring village.[1][2]

Black magic

The Batak people of northern Sumatra are especially notable for the abundance and variety of their ritual arts. Batak people believed that the spirits of dead were able to influence the fortunes of their living relatives, a belief which is shared with many proto-Malay animistic tribes of Indonesia. To gain favor from the ancestor spirits, the Bataks performed elaborate rituals or sacrifices. This knowledge of magic rituals was contained in a book known as the pustaha. The pustaha were created and used by the Batak male religious specialists known as guru by the Karo or datu by the Toba people. The magic knowledge in a pustaha is known as hadatuon (literally "knowledge of the datu"). According to Johannes Winkler (1874-1958), a Dutch doctor which was sent to Toba in 1901 and learned the pustaha from a datu named Ama Batuholing Lumbangaol, there were three types of magic knowledge in the pustaha: the art of sustaining life (white magic), the art of destroying life (black magic), and the art of divination.[2]

Some of the contents of the art of black magic in the pustaha are magical methods to attack enemies, to inflict damage, or to kill enemies. One of the most notable contents of the black magic is the potion known as the pupuk. The pupuk is a powerful substance that can be used to reanimate the spirits of the dead. To create the pupuk, first, the datu must kidnap a male infant from the enemy's village. The datu then raise the kidnapped child carefully so that the child becomes loyal to the datu. Then the datu must tell the child to drink a boiling molten tin. The child will die practically immediately. The body of the child would then be chopped and then mixed with other ingredients e.g. the flesh of animals. The mix is then left to putrefy. The liquid that oozes out of the putrefied mixture is collected and placed into a guri-guri (a kind of cup). The leftover material is burned until they become ash. This ash is known as the pupuk.[3][4]

The murdered child's spirit becomes the pangulubalang, a kind of spirit that can be controlled for many uses. One of the uses of the pupuk is to animate the ancestral statues (debata idup) normally planted on ground around the village. A statue can be "charged" with the pupuk one time, two times, or three times, which render them stronger. A statue that has been charged with the pupuk is similarly known as the pangulubalang. The pangulubalang statues can protect the village or even destroy enemies.[3]

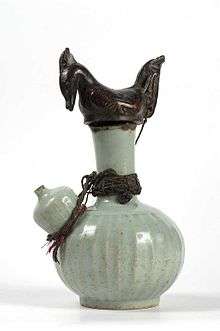

The datu employed a variety of containers made of different materials to hold the pupuk. The Batak people of Toba and Mandailing kept the pupuk in containers made of the horns of the water buffalo, known as the naga morsarang. The Karo people used a container made of the mountain goat's horn (buli buli). Another notable container is the perminaken, a ceramic container that was actually a Chinese ceramic.

Other meaning

The word pupuk is also an Indonesian word for fertilizer.

References

- Causey 2003, p. 263.

- Kozok 2009, pp. 42-4.

- Kozok 2009, p. 43.

- Tobing 1956, p. 167.

Cited works

- Causey, Andrew (2003). Hard Bargaining in Sumatra: Western Travelers and Toba Bataks in the Marketplace of Souvenirs. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824827472.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kozok, Uli (2009). Surat Batak: sejarah perkembangan tulisan Batak : berikut pedoman menulis aksara Batak dan cap Si Singamangaraja XII (PDF) (in Indonesian). École française d'Extrême-Orient. ISBN 9789799101532.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tobing, Philip Oder Lumban (1956). The structure of the Toba-Batak belief in the High God. Jacob van Campen.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

See also

- Tunggal panaluan, a magic staff with a container in which the pupuk may be inserted.

- Porhalaan, a Batak calendar.