Puckle gun

The Puckle gun (also known as the defence gun) was a primitive crew-served, manually-operated flintlock[1] revolver patented in 1718 by James Puckle, (1667–1724) a British inventor, lawyer and writer. It was one of the earliest weapons to be referred to as a "machine gun", being called such in a 1722 shipping manifest,[2] though its operation does not match the modern use of the term. It was never used during any combat operation or war.[3][4] Production was highly limited and may have been as few as two guns.

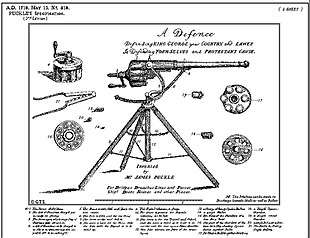

Design and patent

The Puckle gun is a tripod-mounted, single-barreled flintlock weapon fitted with a manually operated[5] revolving cylinder; Puckle advertised its main application as an anti-boarding gun for use on ships. The barrel was 3 feet (0.91 m) long with a bore of 1.25 inches (32 mm). The cylinder held 6 to 11 shots depending on configuration, and was hand-loaded with powder and shot while detached from the weapon.[lower-roman 1][4]

According to the Patent Office of the United Kingdom, "In the reign of Queen Anne, the law officers of the Crown established as a condition of grant that 'the patentee must by an instrument in writing describe and ascertain the nature of the invention and the manner in which it is to be performed.'"[6] This gun's patent, number 418 of 1718, was one of the first to provide such a description. T.W. Lee remarked, however, that "James Puckle's patent in 1718 contains more rhetorical fervor than technical rigor."[7]

Two versions

Puckle demonstrated two configurations of the basic design: one, intended for use against Christian enemies, fired conventional round bullets, while the second, designed to be used against the Muslim Turks, fired square bullets. The square bullets were considered to be more damaging. They would, according to the patent, "convince the Turks of the benefits of Christian civilization". The weapon was also reported as able to fire shot, with each discharge containing sixteen musket balls.[8]

Operation

The Puckle gun firing mechanism is similar to a conventional flintlock musket. After each shot, a crank on the rear of the threaded shaft that ran through the cylinder would be turned, allowing the cylinder to be rotated by hand to the next chamber. Rotating the cylinder would cause a slot and stud mechanism to close the firing pan on the previous chamber and open the next ready to be primed. The crank was then screwed tight again, locking the tapered end of the chamber into the barrel to form a gas-tight seal. The flintlock mechanism was then primed and the weapon fired by operating a long trigger lever which extended down to about the level of the operator's waist.

To reload, the crank handle could be unscrewed completely to detach the cylinder, which could then be replaced with a fresh one. In this way it was similar to earlier breech-loading swivel guns with a detachable chamber which could be loaded prior to use. The cylinder appears to have been referred to as a "charger" in contemporary documentation.[2]

All known examples of Puckle guns have a folding tripod mount. The gun was balanced well on the tripod and could be elevated or traversed by the operator to aim it.

Production and use

A prototype was shown in 1717 to Great Britain's Board of Ordnance, who were not impressed. At a later public trial held in 1722, a Puckle gun was able to fire 63 shots in seven minutes (approximately nine rounds per minute) in the midst of a driving rain storm.[1][8] A rate of nine rounds per minute compared favourably to musketeers of the period, who could be expected to fire between two and five rounds per minute depending on the quality of the troops, with experienced troops expected to reliably manage three rounds a minute under fair conditions; it was however inferior in fire rate to earlier repeating weapons such as the Kalthoff repeater which fired up to six times faster.

The Puckle gun drew few investors and never achieved mass production or sales to the British armed forces. As with other designs of the time it was hampered by "clumsy and undependable flintlock ignition" and other mechanical problems.[1] A leaflet of the period sarcastically observed of the venture that "they're only wounded who hold shares therein". Production was highly limited and may have been as few as just two guns, one a crude prototype made of iron, the other a finished weapon made from brass.[lower-roman 2][8]

John Montagu, 2nd Duke of Montagu, Master-General of the Ordnance (1740-1749), purchased two guns for an unsuccessful expedition in 1722 to capture St Lucia and St Vincent. While shipping manifests state "2 Machine Guns of Puckles" (sic) were among the cargo that departed from Portsmouth,[2] there is no evidence that the guns were ever used in battle.[4]

Surviving examples

Two original examples are on display at former Montagu homes: one at Boughton House and another at Beaulieu Palace House.[2] There is a replica of a Puckle gun at Bucklers Hard Maritime Museum in Hampshire. Blackmore's British Military Firearms 1650–1850 lists "Puckle's brass gun in the Tower of London" as illustration 77, though this appears to have been a gun belonging to the former Montagu estate (at that point owned by the Buccleuch family) on loan to the Tower at the time.[8]

Similar guns

Collier revolver

Elisha Collier invented a flintlock revolver in 1814, nearly a hundred years after the Puckle gun (though examples of flintlock and matchlock revolvers exist much earlier, with the earliest known dating back to the 15th century). Unlike the Puckle, the cylinder of the Collier was not interchangeable, slowing reloading, but would have had a faster rate of fire for its five chambers due to the integral cylinder advancing of its single-action revolver mechanism, self-priming mechanism, and the lack of a need to screw and unscrew the cylinder between shots.

Remington-pattern revolvers

During the period between the widespread adoption of the revolver, but prior to widespread use of cartridges, a common method of increasing reload speed was to replace a revolver's entire cylinder with another pre-loaded one, similar to the Puckle gun.[9] This practice was primarily done on Remington revolvers, as their cylinders were easily removable and were held by a cylinder pin, unlike the early Colt revolvers which were held together by wedges that went through the cylinder pins.[10]

Confederate revolving cannon

A single example of a two-inch bore, five-shot revolver cannon was built and used by the Confederate States of America during the Siege of Petersburg. It was captured on 27 April 1865 by Union troops and sent for examination to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York.[11]

Notes

References

- James H. Willbanks (2004). Machine Guns: An Illustrated History of Their Impact. ABC-CLIO. p. 23.

- "The Armoury of His Grace the Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry" (PDF). University of Huddersfield.

- Brown, M.L. (1980). Firearms in Colonial America : the impact on history and technology 1492-1792. Washington City: Smithsonian Inst. Pr. p. 239. ISBN 0874742900.

- Willbanks, James H (2004). Machine Guns: An Illustrated History of Their Impact. ABC-CLIO. p. 154. ISBN 1-85109-480-6.

- George M. Chinn (1955). The Machine Gun: Design Analysis of Automatic Firing Mechanisms and Related Components, Volume IV, parts X and XI. Bureau of Ordnance, Department of the Navy, US Government Printing office. p. 185.

- "The 18th century". Intellectual Property Office. Archived from the original on 22 April 2014.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Lee, T.W. (2008). Military Technologies of the World. ABC-CLIO. pp. 238–239. ISBN 978-0-275-99536-2. Retrieved 26 December 2019 – via Google Books.

- ffoulkes, Charles (1937). The Gun-Founders of England: With a List of English and Continental Gun-Founders from the XIV to the XIX Centuries. Cambridge University Press. p. 34. Retrieved 26 December 2019 – via Google Books.

- Bequette, Roy Marcot ; edited by James W.; Gangloff, Joel J. Hutchcroft; foreword by Arthur W. Wheaton; chapter introductions by Richard F. Dietz; book design by Robert L. (1998). Remington : "America's oldest gunmaker". Peoria, IL: Primedia. ISBN 1-881657-00-0.

- Robert Niepert. "Civil War Revolvers of The North and South". Florida Reenactors Online. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013.

- Chinn, George M. (1951). The Machine Gun, History, Evolution and Development of Manual, Automatic and Airborne Repeating Weapons, Vol. 1. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 46. Retrieved 26 December 2019 – via Google Books.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Puckle Gun. |

- "The Puckle Gun: Repeating Firepower in 1718" Forgotten Weapons