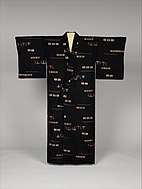

Propaganda kimono

Kimono that carried designs depicting scenes from contemporary life became popular in Japan between 1900 and 1945. Such designs are now known as omoshirogara (面白柄) — literally, "interesting" or "novelty" designs.[1] They include traditional Japanese apparel worn by men, women and children, including nagajuban (underkimono); haori (jackets worn over kimono); haura (decorative inner linings of haori); and miyamairi kimono[2] (kimono used for infants when taken to a Shinto shrine to be blessed). The designs that concentrate on reflecting military and political concerns in Japan during Japan's war years (1931-1945) are commonly referred to as propaganda kimono.[3][4] Omoshirogara garments were typically worn inside the home or at private parties, during which the host would show them off to small groups of family or friends.[5]

History

Among the factors that led to the emergence of omoshirogara / propaganda kimonos, three stand out: the introduction of modern textile manufacturing and printing equipment into Japan in the late 19th century allowed textile manufacturers to produce printable apparel fabric more quickly and cheaply;[6] the social and political impetus for Japan to modernize;[7] and, following the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, the political leadership's desire to rally the population in support of Japan's colonial expansion and, eventually, its war against the Allies.[4]

Much of the imagery used on propaganda kimonos was widely used on other media and consumer goods, such as popular magazines, toys, posters and dolls.[8][9] Some of the typical omoshirogara designs from the early 1920s to the mid-1930s focused on the outward signs of modernity, depicting a sleek, westernized, consumerist future – cityscapes with subways and skyscrapers, ocean liners, steaming locomotives, sleek cars and airplanes, while others showed images reflecting current events (e.g., the visit of the Graf Zeppelin)[10] and social tends, such as of images of the "modern girl" with symbols of the new pastimes she supposedly enjoyed, such as cocktails, nightclubs and jazz.[11] But no matter what the subject, the designs employ a bold palette and show direct influences of social realism, Art Deco, Dadaist, and Cubist collage, early cartoons, and other graphic media.[9][12]

By the later 1920s and especially following the crash in 1929 (and Japan's economically disastrous return to the gold standard), conservative and ultra-nationalist forces in the military and government elites began to push back against the modernist trends and reasserted more traditional values.[13] Military power, the will to use it, and the ability to manufacture its hardware became ever more central to Japan's self-image. As a result, the propaganda kimono designs took on an increasing militaristic air.[8]

It is only in recent years that scholars in Japan, Europe and the United States have begun to seriously study Japanese propaganda kimonos.[14] In 2005, The Bard Graduate Center mounted one of the first major exhibits[15] of these kimono, curated by Jacqueline M. Atkins, an American textile historian and recognized scholar of Japanese 20th century textiles. The exhibition also was shown at the Allentown Art Museum and the Honolulu Academy of Art (2006-2007).[15] The Metropolitan Museum of Art,[16] The Johann Jacobs Museum[17] (Zurich), the Edward Thorp Gallery[18] in New York City, and the Saint Louis Art Museum[19] have mounted exhibits that have included propaganda kimono, and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts has received a significant donation of wartime and other omoshirogara kimono from an American collector.[20]

Collections

_with_Scene_of_the_Russo-Japanese_War_featuring_General_Nogi_MET_DP277727.jpg) Man’s under-kimono (nagajuban) with scene of the Russo-Japanese War

Man’s under-kimono (nagajuban) with scene of the Russo-Japanese War_with_%E2%80%9CItaly_in_Ethiopia%E2%80%9D_Symbols_MET_DP330773.jpg) Man’s under-kimono (nagajuban) with “Italy in Ethiopia” symbols

Man’s under-kimono (nagajuban) with “Italy in Ethiopia” symbols Woman’s kimono with planes and Hinomaru flags

Woman’s kimono with planes and Hinomaru flags Kimono celebrating animals' role in Japan's Manchurian war effort

Kimono celebrating animals' role in Japan's Manchurian war effort

References

- Atkins, Jacqueline M. (September 2008). "Omoshirogara Textile Design and Children's Clothing in Japan 1910-1930". Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. Paper 77. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- "Miyamairi". traditionscustoms.com.

- Wakakuwa, Midori (2005). "War-Promoting Kimono (1931-45)". Wearing Propaganda Textiles on the Home Front in Japan, Britain, and the United States 1931–1945. Yale University Press. pp. 183–204.

- Dower, John W.; Morse, Anne Nishimura; Atkins, Jacqueline M.; Sharf, Frederic A. (2012). The brittle decade : visualizing Japan in the 1930s (1st ed.). Boston: MFA Publications. ISBN 0878467696.

- Kashiwagi, Hiroshi (2005). "Design and War: Kimono as 'Parlor-Performance' Propaganda". In Atkins, Jacqueline M. (ed.). Wearing Propaganda Textiles on the Home Front in Japan, Britain, and the United States 1931–1945. Yale University Press. pp. 171–182.

- Deacon, Deborah A.; Calvin, Paula E. (2014). War Imagery in Women's Textiles : A worldwide study of weaving, knitting, sewing, quilting, rug making and other fabric arts. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. p. 130. ISBN 0786474661.

- Brown, Kendall H.; et al. (2002). "Flowers of Taisho Images of Women in Japanese Society and Art, 1915-1933". Taishō chic: Japanese modernity, nostalgia and deco : [exhibition, Honolulu academy of arts, January 31 to March 15, 2002] (2. print. ed.). Honolulu: Honolulu academy of arts. pp. 17–22. ISBN 0-295-98244-6.

- Dower, John W.; Morse, Anne Nishimura; Atkins, Jacqueline M.; Sharf, Frederic A. (2012). "Wearing Novelty". The Brittle Decade : visualizing Japan in the 1930s. MFA Publications. pp. 91–143.

- Kaneko, Maki (2016). "War Heroes of Modern Japan: Early 1930s War Fever and the Three Brave Bombers". In Hu, Philip K.; et al. (eds.). Conflicts of Interest: Art and War in Modern Japan (1st ed.). Saint Louis Art Museum. pp. 69–82.

- Grossman, Dan (August 15, 2010). "Graf Zeppelin's Round-the-World flight: August, 1929". airships.net. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

The ship landed to a tumultuous welcome and massive press coverage in Japan

- Atkins (2005). "Extravagance is the Enemy". Wearing Propaganda. pp. 156–170.

- Atkins, Jacqueline M. (2005). "An Arsenal of Design: Themes, Motifs and Metaphors in Propaganda Textiles". Wearing Propaganda: Textiles on the Home Front in Japan, Britain, and the United States 1931–1945 (1st ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 258–365.

- Gordon, Andrew (2009). "The Depression Crisis and Responses". A modern history of Japan: from Tokugawa times to the present (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 181–195. ISBN 978-0-19-533922-2.

...this move brought disaster.

- Atkins, Jacqueline M. (2005). "Introduction". Wearing Propaganda. Yale University Press. pp. 24–28.

- "Wearing Propaganda: Textiles on the Home Front in Japan, Britain, and the United States 1931–1945". Bard Graduate Center. Archived from the original on 2016-08-07.

- "Kimono: A Modern History". The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- "Omoshirogara". Johann Jacobs Museum. Archived from the original on 2018-01-17.

- "Japanese Propaganda Kimonos". Edward Thorp Gallary. Archived from the original on 2017-09-06.

- "Conflicts of Interest: Art and War in Modern Japan". Saint Louis Art Museum. Archived from the original on 2017-10-16.

- Museum of Fine Arts Boston, online Artwork archive. "Fourteen (14) Japanese propaganda-print garments and one obi". mfa.org. Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

Gift of Norman Brosterman, East Hampton, NY to the MFA. (Accession date: May 19, 2010)