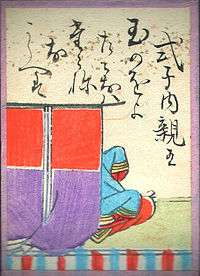

Princess Shikishi

Princess Shikishi (式子内親王 Shikishi Naishinnō) (1149 – March 1, 1201) was a Japanese classical poet, who lived during the late Heian and early Kamakura periods. She was the third daughter of Emperor Go-Shirakawa (1127–1192, reigned 1155–1158). In 1159, Shikishi, who did not marry, went into service at the Kamo Shrine in Kyoto. She left the shrine after some time, and in her later years became a Buddhist nun.

Shikishi is credited with 49 poems in the Shin-Kokin Shū, a collection of some 2,000 popular works compiled in the early Kamakura period, and many other poems included in the Senzai Waka Shū, compiled in the late Heian period to commemorate Emperor Go-Shirakawa's ascension, and later compilations.

The poet's name is sometimes also pronounced Shokushi (both are on-yomi readings). Modern given names using the same characters include Shikiko (mix of on- and kun-yomi) and Noriko (pure kun-yomi). Her title, Naishinnō (内親王), means "Imperial Princess".

Biography

Though her exact date of birth is unknown, it is estimated that Princess Shikishi was born in 1150, and she died in the year 1201. She was the third daughter of Goshirakawa, seventy-seventh emperor of Japan beginning in the year 1155. During her lifetime, Japan saw turbulent times like the Hōgen and Heiji Disturbances (1156 and 1159), which involved competing samurai clans vying for political power. There were also numerous natural disasters, including a tornado, a famine, and an earthquake, all of which wreaked destruction on Japan's inhabitants.

During all this action, Shikishi was cloistered away for much of the time. In 1159, the Kamo Shrines chose her to be their thirty-first saiin, a vestal virgin or high priestess. An emperor-appointed position, the saiin represented the emperor by attending to the primary deities at the major Shinto shrines. To be saiin was an important and luxurious job—she factored largely in the annual rite, called the Kamo no Matsuri or Aoi Matsuri, which was celebrated with a great festival every year. She also had many attendants and lived in her own palace, but saiin could be a rather lonely appointment, as the girl would move away from her family and remain mostly separate from the public. As saiin, Shikishi would have lived near the capital, and her large number of attendants provided ample company; however, this career came with many restrictions and the government policies at the time made it difficult for princesses to marry. Shikishi remained in this position for ten years until she became ill, forcing her to depart the shrine in 1169. She dealt with several illnesses over the rest of her life, including what was probably breast cancer.

Around 1181, Shikishi became acquainted with Fujiwara no Shunzei, a famous poet of the time with whom she may have studied, and developed a friendship with his son Teika. Teika was also a renowned poet, and it is speculated that Shikishi and Teika were in a relationship. Much of Shikishi's poetry contains a tone of saddened longing, which has led some to believe she dealt with unrequited or unattainable love. Teika kept a thorough journal, in which he chronicles his visits to Shikishi. He and Shunzei would often visit her together, but Teika does not go into detail about these visits, though his concern for her appears in entries during the time when Shikishi's illness was worsening. A couple of times he wrote that he remained through the night, including a time Shikishi was especially ill and he stayed in “the northern corner of the kitchen.” Scholars disagree about whether or not Shikishi and Teika were lovers, and the evidence is too small to be certain either way. In the 1190s, Shikishi took Buddhist vows to become a nun and adopted the name Shōnyohō, as she had become a believer in Pure Land Buddhism. Also in the 1190s, there were two separate instances of rumors that she had cursed notable women, one of the instances involving a plot against the government; and some believe she took the vows partly to escape punishment. No action was taken regarding either of these accusations, however.

Shikishi was appointed as foster mother in 1200 to the future Emperor Juntoku, and also during this year she wrote a set of one hundred poems for the Shōji ninen shodo hyakushu, the First Hundred-Poem Sequences of the Shōji Era, which was sponsored by her nephew, the Retired Emperor Go-Toba. Go-Toba had directed all notable poets in this year to submit some of their works for this anthology, and Shikishi wrote this set of poems in only twenty days despite being extremely ill. Beginning with twenty-five, eventually forty-nine of Shikishi's poems were chosen for the eighth imperial anthology, the Shin-Kokin Waka Shū (as opposed to only nine of Teika's), which altogether contained 1,979 poems. For the two decades between Shikishi and Teika's first meeting and Shikishi's death, Teika's diary displays some of the ongoing health struggles Shikishi had until her death in 1201.

Poetry

399 of Shikishi's poems are known of today, many of which are part of three sets: Sequences A, B, and C. The poetry form Shikishi used was called tanka, which involves grouping syllables into a set of 5-7-5-7-7. As this form was rather limited, the most widely used way of experimentation lay in stringing together several sets of these 5-7-5-7-7 lines to make longer poems. Sequences A, B, and C were written in hundred-tanka sequences, called hyakushu-uta, and the rest of her poems are in smaller sets of tanka. Though it is difficult to be certain, Sequence A is thought to have been written sometime between 1169 (perhaps earlier) and 1194. It is believed that Sequence B was written between 1187 and 1194, and it is known for certain that Sequence C, the one she wrote for Go-Toba's poetry collection, was written in 1200 shortly before she died. Sequences A and B both abide by the same subjects and numbers: Spring, 20 poems; Summer, 15 poems; Autumn, 20 poems; Winter, 15 poems; followed by Love, 15 poems; and Miscellany, 15 poems. Sequence C contains the typical set of seasonal poems: 20 for Spring and Autumn, and 15 for Summer and Winter; followed by Love, 10 poems; Travels, 5 poems; Mountain Living, 5 poems; Birds, 5 poems; and Felicitations, 5 poems. The many tanka in a hyakushu-uta each focus on a single component of the greater concept of the poem, coming together to form an interconnected whole. Tanka often made use of the literary technique kake-kotoba, a method that involved using homonyms and homophones. For example, one of Shikishi's tanka reads:

As spring comes my heart melts, and I forget how like the soft snow I go on fading

Haru kureba kokoro mo tokete awayuki no aware furiyuku mi o shiranu kana

In this poem, the segment “furu” of the word “furiyuku” means “to fall” (like snow) and also “to grow old.” The poem's use of kake-kotoba connects the idea of the narrator's heart softening at the season's change to the idea that she is aging. Shikishi also used a device called engo, or “related word.” Engo involves tying together imagery in a poem by using words that evoke similar ideas. In one poem she writes:

Wind cold, leaves are cleared from trees night after night, baring the garden to the light of the moon

Kaze samumi ko no ha hare yuku yo na yo na ni nokoru kuma naki niwa no tsukikage

Here, the word “hare,” meaning “cleared” (“leaves are cleared”), also connects to the image of the clear light of the moon, “tsukikage.” Another more content-based technique that appears in Shikishi's writing is honka-dori, the taking of a passage by another poet and incorporating it into one's own work, without acknowledgement. Some may be uncomfortable with this technique, considering its resemblance to plagiarism. However, considering the restrictive structure of tanka, the limited subjects poets were allowed to write on, and the closed-off nature of Kyoto at this time, it is not surprising that different poets’ work would gradually begin to sound similar. Also, within Chinese methods of poetry writing which influenced Japanese poets, including someone else's work within one's own was seen as a tribute paid to another author, not an act of stealing. There are differences in the ways scholars translate Shikishi's poetry. Compare the two translations of one of Shikishi's works here, the first by Earl Miner and the second by Hiroaki Sato:

Original:

Tamano’o yo taenaba taene nagareba shinoburu koto no yowari mozo suru

Miner's translation:

O cord of life! Threading through the jewel of my soul, If you will break, break now; I shall weaken if this life continues, Unable to bear such fearful strain.

Sato's translation:

String of beads, if you must break, break; if you last longer, my endurance is sure to weaken

Here is one of Shikishi's poems from Sequence A, translated by Sato.

Spring: 20 poems

In spring too what first stands out is Mount Otowa: from the snow at its peak sunrays appear

Though warblers have not called, in the sound of cascades pouring down the rocks spring is heard

Through a bud-tinted plum tree the evening moon begins to show light of spring As spring comes my heart melts, and I forget how, like soft snow, I go on fading

As I look around, now here, now there, it's covered with spring robes, their woof feeble still

Isolate my life, seclude it with layers of haze, deeply, at the food of the Hill of Gloom

It's spring: to my heart's content I gaze at the treetops shrouded in haze and budding

Opening on plum twigs in unfaded snow, the first blossoms for dyeing bring back the past

In whose abode did they touch plum blossoms? The scent transferred so distinct on your sleeves

Plum blossoms accompanied by a tinge of love: their scent on your coat, distinct, unfaded

About blossoms I do not know; there, not there, I look around: haze fragrant on a spring dawn

Would there were other means of consolation than flowers: coldly they fall, coldly I watch

When I count the seasons past, fleeting, so many springs wistful of flowers I’ve come through

Everyone, look at Yoshino's mountain peaks! Are the clouds cherry, the blossoms white snow?

I do not know about hilltops with cherry in bloom; now in spring haze a thousand hues fade

A spring breeze must have passed the gable eaves: the accumulated snow fragrant where I lie

In the moonlight remaining after daybreak, faintly falling blossoms hidden among leaves

Warblers, too, wearied as spring ends; no more visits at night and my house is desolate

The geese, now heading for home, can't help saying farewell to the clouds aglow at dawn

Today's the last; haze with its hues rises and parts, spring at sunset in the hilltop sky

A few of her other poems, not included in Sequences A, B, or C:

After resigning the vestal’s post at Kamo, on the Day of the Sacred Tree during the festival someone brought her a gift of aoi to offer her. She wrote on it: At the foot of the god's hills I grew used to aoi; since I parted with it years have passed

Among the poems on “Love”: Does he know: some thoughts, like dayflowers, cling to someone and intensify in color?

What to do? Like the waves beating on the beach, I, in unknown love, am shattering myself

Untitled: If no one kept what passes in traces of a brush, how could we meet the unknown past?

Recognition

Shikishi was recognized in fifteen out of twenty-one imperial anthologies. Fujiwara no Shunzei included nine of Shikishi's works in the Senzai Waka Shū, the seventh imperial anthology, containing 1,288 poems. The eighth imperial anthology, the Shin-Kokin Waka Shū, compiled shortly after her death, included forty-nine of her poems. 155 of her poems are incorporated throughout the seventh imperial anthology to the twenty-first.

See also

- Fujiwara no Teika

- Hyakunin Isshu

References

- Kokugo Dai Jiten Dictionary, Shinsou-ban (Revised edition), Shogakukan, 1988.

- Hiroaki Sato, translator. String of Beads: Complete Poems of Princess Shikishi. University of Hawaii Press, 1993. ISBN 0-8248-1483-5.

- Rodd, Laurel Rasplica. “Shikishi Naishinnō.” Dictionary of Literary Biography, vol. 203, 1999, pp. 261–264. EBSCO: Biography Reference Bank (H. W. Wilson):517989849

External links

- photo—from an edition of Hyakunin Isshu, an anthology of waka poems; 89/100 from etext.lib.virginia.edu/japanese/hyakunin/frames/index/hyaku3euc.html

- photo—from Hyakunin Isshu card game, modern era

- Biography—from BookRags