Pratylenchus penetrans

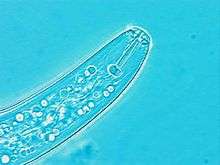

Pratylenchus penetrans is a species of nematode in the genus Pratylenchus, the lesion nematodes. It occurs in temperate regions worldwide, regions between the subtropics and the polar circles. It is an animal that inhabits the roots of a wide variety of plants and results in necrotic lesions on the roots. Symptoms of P. penetrans make it hard to distinguish from other plant pathogens; only an assay of soil can conclusively diagnose a nematode problem in the field. P. penetrans is physically very similar to other nematode species, but is characterized by its highly distinctive mouthpiece. P. penetrans uses its highly modified mouth organs to rupture the outer surface of subterranean plant root structures. It will then enter into the root interior and feed on the plant tissue inside. P. penetrans is considered to be a crop parasite and farmers will often treat their soil with various pesticides in an attempt to eliminate the damage caused by an infestation. In doing this, farmers will also eliminate many of the beneficial soil fauna, which will lead to an overall degradation of soil quality in the future. Alternative, more environmentally sustainable methods to control P. penetrans populations may be possible in certain regions.[1]

| Pratylenchus penetrans | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Superfamily: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | P. penetrans |

| Binomial name | |

| Pratylenchus penetrans (Cobb, 1917) Filipjev and Schuurmans Stekhoven, 1941 | |

Hosts and symptoms

Root lesion nematode has a wide host range, including hosts like apple, cherry, conifers, roses, tomato, potato, corn, onion and sugarbeets, and ornamentals such as Narcissus.[2] More than 164 hosts for P. penetrans have been recorded.[1][3] In the host range there are some hosts that are susceptible, such as wheat, oat, field pea, faba bean, and chickpea, and some that are moderately susceptible, such as barley and canola.[4]

Some general symptoms that are produced on infected plants include poor growth, fruit spot, and chlorotic foliage.[1] These secondary symptoms are often due to plant root stress.[5] These make it rather difficult to diagnose nematode diseases in general. The roots when infected produce necrotic lesions, which are darkened areas of dead tissue, on the surface and throughout the cortex of the infected roots. These lesions turn the root to reddish-brown to black and are initially spotty. As the nematode continues to feed, the lesions can coalesce to become large necrotic areas of tissue that may eventually girdle the root.[5] The population size of the nematode affects the degree of symptoms. Low to moderate populations may cause no visible above ground symptoms, while high populations can lead to stunting, nutrient and water deficiencies, and eventual die-back of the plant.[5] On potato, infection of root lesion nematode can cause a secondary invasion by Verticillium dahliae leading to Potato Early Dying.[1] Onions are another important host of P. penetrans. Onions are an important vegetable for consumption in the United States and upon infection the nematodes can limit yield and quality of the bulbs. Populations of more than 0.01 nematode per cubic centimeter of soil resulted in injury to onions. There is a negative relationship between the increasing inoculum levels on onion root and top fresh weight at harvest.[6]

Lifecycle

Pratylenchus penetrans is a migratory nematode which means it moves from root to root and is also an endoparasite which means go into the roots. There are both female and male nematodes, with distinguishing differences being a spicule for the males and that males have a bent tail while females have a straight tail. They reproduce sexually, with the females laying single eggs in the root or soil.[1] After embryonic development within the egg to the first stage juvenile (J1), the nematode molts to the second-stage juvenile (J2) and hatches from the egg.[5] The nematode then molts from the J2 to J3, J3 to J4, and finally J4 into an adult. J2, J3, J4, and adults all have a vermiform, worm-like shape, and can all invade the roots.[1] Entry into the roots is accomplished by mechanical pressure and cutting action of the stylet of the nematode, usually just behind the root cap but may occur through other surfaces of the roots, rhizomes, or tubers.[3] The nematode feeds on the cells within the root, usually until the cell lyses and cavities are formed. Then the nematodes move forward within the root to feed on healthy plant cells.[5] Since P. penetrans is a migratory nematode, they can move from plant to plant, but usually do not migrate more than 1–2 meters from the root zone that they first infect,[5] thus invasion of many roots can take place in the nematodes life span.[1] The nematode overwinters in infected plant parts or in the soil at any life stage, however J4 is the optimal life stage.[5]

Environment

The nematode is found in all temperate regions around the world, because of the wide host range. For normal nematode activity a moisture film is needed for movement of the nematode. Soil moisture, relative humidity, and related environmental factors directly affect nematode survival. Moisture is needed to the nematode to survive and move. When the nematode is inside of the root, the root provides the optimal moisture and protection from desiccation. P. penetrans has a critical survival mechanism that during cold seasons and in the absence of the host it goes into diapause, animal dormancy resulting in a delay in development. Root lesion nematode also has the capability of having extreme states of anhydrobiosis. During anhydrobiosis the nematode enters an almost completely desiccated state which stabilizes its membranes and other cellular structures, preventing otherwise lethal damage caused by environmental extremes. However, in general this is not considered a successful strategy for the nematode.[7] pH levels of the soil are also a factor of nematode activity. In a study, it was shown that a pH of 7 favored the multiplication of nematodes more than a pH of 9 or 3 in sandy loam and sandy clay soil[.[8]

The number of eggs deposited, life cycle completion time, and juvenile mortality rates are all affected by temperature. In a study different temperatures were tested, 17 °C, 20 °C, 25 °C, 27 °C, and 30 °C. Eggs deposited per day measured 1.2, 1.5, 1.6, 1.8, and 2.0, respectively. Lifecycle completion time also corresponded with temperature, decreasing as the temperature increased, 46 days at 17 °C and 22 days at 30 °C. Finally, juvenile mortality rates were higher at when the temperature was lower than 25 °C around 50.4% and higher than 27 °C around 58.4%. Between 25 °C and 27 °C it is 34.6 and 37.6% respectively. However, with all of these factors taken into consideration it was found that P. penetrans reproduces over a wide range of temperatures.[9]

Management/control

Initial inoculum

The best way to prevent disease caused by Pratylenchus penetrans is to prevent the initial introduction of inoculum into the field.[5] Without nematodes in the field disease cannot occur, however there are very few fields that are not infected with some amount of root lesion nematodes. One way this can be done is through fumigation of the field prior to planting to decrease the number of nematodes in the field.

Resistance

There are some resistant varieties of hosts that will not be affected by the pathogen. Moderate resistance is presently limited to only a few cultivated crops including forage legumes and potato.[5] There are not very many varieties with a high degree of resistance but it has been shown that Peconic and Hudson varieties of potato have shown some resistance.[3]

Cultural practices

There are also cultural practices that can be helpful in management of P. penetrans including clean planting stock, fallowing, and cover crops.[10] Crop rotation is usually not feasible in management of the disease because of the wide host range of the pathogen.[1] Rotations to nonhost crops offers limited opportunities due to nematodes being able to live in the soil.[5]

Control practices

Chemical control has been shown to have the best effect on levels on nematode concentrations. Nematicides that are put on the field prior to planting has been shown to reduce inoculum levels, but may have negative effects on the crop that is planted.[1] Pre-plant fumigation is most effective to reduce field population levels to below economic damage thresholds.[5]

Newer methods

An area of ongoing research is using ornamental species to reduce inoculum levels of nematodes in the fields. Growing Tagetes marigolds has been shown to reduce Pratylenchus numbers by 90%. Other ornamentals such as Helenium, Gaillardia, and Eriophyllum also suppress P. penetrans.[11]

All of these tactics require accurate diagnosis of species and identification of population levels assessed from soil and root samples taken from the field.[5] Certain factors like expense and types of crops have influences on the types of control methods employed. When combating Pratylenchus penetrans several methods of control and management are usually employed for controlling the disease.[10]

Importance

Root lesion nematodes are third behind root knot and cyst nematodes for the greatest economic impacts on crops worldwide.[5] It is the most important nematode pest in the northeastern United States. Plant varieties susceptible to the respective fungi are damaged even more when the plants are infected with the nematodes, with the combined damage being considerably greater than the sum of the damages caused by each pathogen acting alone.[10] In potatoes it has been shown that Pratylenchus penetrans has a relationship with Verticillium dahliae in causing Potato Early Dying Syndrome.[1] Potato Early Dying causes premature vine death, severe yield losses, scabby appearance with sunken lesions, and dark, wart-like bumps that turn purple on tubers in storage.[1] The fungus is not shown to be transmitted by the nematode, however it has an increased ability to infect because of the mechanical damage caused by root lesion nematodes.[10] Also documented. is that varieties ordinarily resistant to Verticillium apparently becomes infected by it after previous infection by Pratylenchus.[10]

References

- Pratylenchus penetrans Archived 2013-08-11 at Archive.today. Entomology and Nematology. University of California, Davis.

- Slootweg 1956.

- Hooker, W. J. "Lesion Nematodes". Compendium of Potato Diseases. 1981. Print.

- Wherrett, Andrew, and Vivien Vanstone. "Root Lesion Nematode". Soil Quality. Healthy Soils for Sustainable Farms, 2014. Web. 9 Nov. 2014.

- Davis, Eric L., and Ann E. MacGuidwin. "Lesion Nematode Disease". The Plant Health Instructor (2000): 1030-032. The American Phytopathological Society, 2014. Web. 9 Nov 2014.

- Pang, W., S. L. Hafez, P. Sundararaj, and B. Shafii. "Pathogenicity of Pratylenchus Penetrans on Onion". Nematropica 39.1 (2009): 35-46. Cabdirect. Web. 9 Nov. 2014.

- McSorley, Robert. "Adaptations of Nematodes to Environmental Extremes". The Florida Entomologist 86.2 (2003): 138. ProQuest.Web. 9 Nov. 2014.

- Madan, LaI, and R. K. Jauhari. "Effect of Soil PH on the Population of Migratory Nematode Pratylenchus Penetrans (Cobb, 1917) (Nematoda: Hoplolamidae) on Tea Plantations in Doon Valley". Journal of Experimental Zoology 10.2 (2007): 469-71. Cabdirect. Web. 9 Nov. 2014.

- Mizukubo, Takayuki, and Hiroshi Adachi. "Effect of Temperature on Pratylenchus Penetrans Development". The Journal of Nematology 29.3 (1997): 306-14. NCBI. Web. 9 Nov. 2014.

- Agrios, George N. "Plant Diseases Caused By Nematodes: Lesion Nematode, Pratylenchus". Plant Pathology. 5th ed. New York: Academic, 1969. 849-53. Print.

- "Nematode, Northern Root Lesion (Pratylenchus Penetrans)". Plantwise Knowledge Bank. Knowledge Bank, 2014. Web. 9 Nov. 2014.

Bibliography

- Slootweg, A.F.G. (1 January 1956). "Rootrot of Bulbs Caused By Pratylenchus and Hoplolaimus Spp". Nematologica. 1 (3): 192–201. doi:10.1163/187529256X00041. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

External links

- Pratylenchus penetrans. Nemaplex. University of California, Davis.