Pottenstein Castle

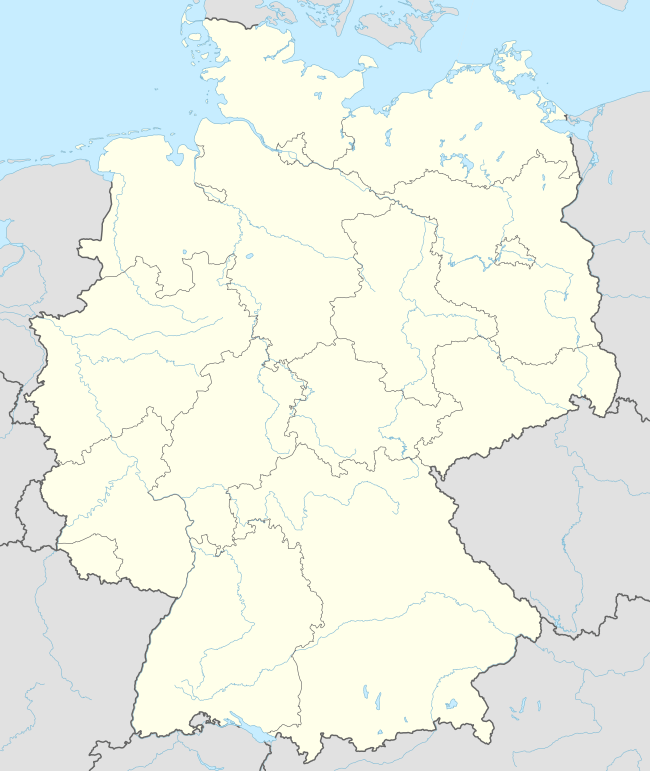

Pottenstein Castle (German: Burg Pottenstein) is one of the oldest castles in Franconian Switzerland, a region in the German state of Bavaria. It stands on a rock above the eponymous town of Pottenstein in the Upper Franconian county of Bayreuth. The castle is home to a museum and both may be visited for a fee.

| Pottenstein Castle | |

|---|---|

| Pottenstein | |

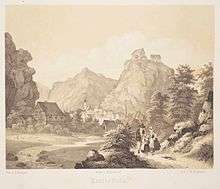

Pottenstein Castle seen from the south | |

| |

| Coordinates | 49°46′12″N 11°24′29″E |

| Type | hill castle, spur castle |

| Code | DE-BY |

| Height | 410 m above sea level (NN) |

| Site information | |

| Condition | partly preserved |

| Site history | |

| Built | between 1057 and 1070 |

| Garrison information | |

| Occupants | free nobles; later an administrative castle of the Bishopric of Bamberg |

Location

The spur castle is located within the Franconian Switzerland-Veldenstein Forest Nature Park at a height of roughly 410 metres on a west-facing hill spur between the valleys of the Püttlach and the Weihersbach, immediately southeast and above the town of Pottenstein, about 22 kilometres southwest of Bayreuth.

In the vicinity are other castles: to the west are Gößweinstein Castle, Kohlstein Castle and the ruins of the Upper and Lower Castles in Tüchersfeld, to the east are the ruins of Hollenberg Castle and sites of Wartberg and Böheimstein castles.

History of the castle

Foundation

Around 1050, the village of Pottenstein belonged to Margrave Otto of Schweinfurt and, after his death in 1057, went to his third daughter, Judith. Judith's first marriage was to Duke Cuno of Bavaria. Cuno died in 1055 and in 1057 Judith married Boto, the younger brother of Count Palatine Aribo II of the edelfrei family of the Aribonids. In 1070 h referred to himself as comes de Potensteine , i.e. the Count of Pottenstein.

The castle that bore his name (Stein i.e. "rock" of Boto) must therefore have been built between 1057 and 1070 by Boto. It was probably originally established to guard the area between the Upper Main and Pegnitz to the southeast.

There is no clear documentary evidence for an alternative theory that the castle was built around 918 by King Conrad I.

Administrative castle of the Bishopric

Boto died in 1104 with heirs and was buried in Theres Abbey. Judith had died in 1066.

From the fact that the castle is not among the acquisitions of Otto I the Holy, who from 1102 to 1139 held the title of bishop, it can be concluded that Boto had sold the castle during his lifetime before or in 1102 to the Bamberg diocese. Around 1118 and in 1121, Bishop Otto I resided at the castle.

During the following centuries, Pottenstein Castle was entrusted by the bishops of Bamberg to a ministerialis family who renamed themselves after the castle. The oldest known members of the family was a Wezelo of Pottenstein around 1121; in 1169 there was a Rapoto of Pottenstein. He was followed by Erchenbert or Erchenbrecht of Pottenstein from 1185 to 1221, but from about 1207 he was also a truchsess or steward to the bishop. His brother Henry called himself von Pottenstein. Other members of the family followed, including a Conrad of Pottenstein in 1240-1248, who was a cathedral canon from 1242.

From 1227 to 1228 Pottenstein Castle served as a temporary residence for Saint Elizabeth, Landgravine of Thuringia.

Between 1323/1327 and 1348 the castle became the seat of an amt or administrative base for the Bishopric of Bamberg. In 1348 a Gebhard Storo was the amtmann in Pottenstein.

Pottenstein was the centre of an extensive judicial district. The administrative area of Pottenstein was enlarged by the incorporation of smaller episcopal offices: in 1492 the Amt of Tüchersfeld, in 1594 Amt Leienfels and in 1628-1636 Amt Gößweinstein.

From the beginning of the 14th century, the castle was managed by a vogt or advocate, who had his seat in the Vogteihaus in the lower ward. This Vogteihaus was referred to in 1728 and 1743 as the Old Vogtei, the vogt had meanwhile moved, probably in 1728, to a building in the town, at the latest in 1748 he moved into the Vogthaus, which was purchased in 1745 and rebuilt in 1748/1749. The reason for the move was the arduous climb up to the hill castle. The only known noble vogt was Walter of Streitberg in 1332, the later vogts, who held office in the late 16th century, were members of the bourgeois estate.

From 1500, the officers called themselves pflegers. They were based in the so-called cabinet in the upper ward. In 1750 the pfleger of the castle also moved into the Vogthaus in the town. The castle was abandoned as an administrative residence and served as a corn granary.

Warlike events

During bitter fighting in 1125 between King Lothair III and the Hohenstaufen anti-king, Conrad III, the town of Pottenstein was destroyed by fire but the castle survived.

During the Peasants' War, however, it was occupied and plundered by peasants in 1525 but for fear that plummeting and burning debris could also damage houses in the town below, it was not razed. In addition, without the castle, the peasants would have been without protection against the forces of the count Palatine, the margrave and the city of Nuremberg.

The Second Margrave War, in which Albert Alcibiades, Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach and Bayreuth launched numerous raids and looting, resulted in heavy damage and led to the destruction of many villages and castles in the Empire, especially in Franconia. On 18 May 1553, Pottenstein Castle was bombarded and occupied by margravial troops. Even the castle chapel in the upper ward was destroyed and was no longer mentioned after 1553. The cost of the damage, 20,000 guilders, indicates that it was not only the outer ward that was captured.

In 1634 during the Thirty Years' War a raid by the Swede, Colonel Cratz, failed to take the castle. A trumpeter who pretended to have been sent by the imperial troops, appeared before the castle. He was escorted over the drawbridge, but when the defenders noticed the enemy waiting outside, they quickly drew the drawbridge up. The captured trumpeter was executed after converting to Catholicism.

In 1703/1704, during the Spanish Succession War, a garrison was installed in the castle, and it was occupied by soldiers again in 1708 in 1712. In 1703, an oven was installed in the already dilapidated bergfried for the garrison troops.

After this time no further warlike events at the castle are recorded.

Private ownership

After the transfer of the diocese in 1803 to the Bavarian state during the secularisation period the castle fell into ruins. In 1878, the castle came into the possession of Nuremberg pharmacist, Dr. Heinrich Kleemann, to whom the preservation of the ruins, which were then threatened by demolition, is owed. He died in 1890 and his widow sold the castle in 1900.

In 1918, Pottenstein Castle was purchased by the father castellan Winzelo, Baron of Wintzingerode, who died in 2006 and whose noble family was seated at Bodenstein Castle in Thuringia. His life's work was the construction of the museum and the ongoing renovation of the castle complex. The castle is still owned by the family.

The castle is now a privately run museum and residence where prehistoric and early historical objects are displayed along with a collection of weapons, books, autographs and three show rooms grouped as an ensemble.

The Elizabeth Room in the former tower house, the western part of the palas, commemorates the stay of Saint Elizabeth in 1227-1228. The accessible areas are the upper floor of the main building (great hall, Red Salon, Elizabeth Room), the remnants of the former bergfried, the well house (porcelain, glass, ceramics and ethnographic objects) and the tithe barn (with tithe exhibits, an exhibition on the recent history of castle and changing special exhibitions). In addition to the impression of a well-preserved castle of the 16th century with a medieval substance, visitors may also tour the castle gardens with their outstanding views over the town and countryside.

Murder at the castle

On 2 April 1866, Max Söhnlein, who had just been released from Bayreuth Gaol, killed the wife of the castle guard with a pick in the presence of her infant. Max Söhnlein was the son of a former castle guard and committed the murder to conceal a crime. He wanted to steal clothes and money, when he realized that his parents no longer lived at the castle. He was arrested shortly thereafter in Pegnitz and sentenced on 7 May 1866 to life imprisonment at a trial by jury in Bayreuth. Due to his youth - he was only 20 years old - the usual death penalty could not be imposed.

Literature

- Kai Kellermann: Herrschaftliche Gärten in der Fränkischen Schweiz – Eine Spurensuche. Verlag Palm & Enke, Erlangen und Jena, 2008, ISBN 978-3-7896-0683-0, pp. 154–163.

- Rüdiger Bauriedel, Ruprecht Konrad-Röder: Mittelalterliche Befestigungen und niederadelige Ansitze im Landkreis Bayreuth. Ellwanger Druck und Verlag, Bayreuth, 2007, ISBN 978-3-925361-63-0, p. 138.

- Ursula Pfistermeister: Wehrhaftes Franken – Band 3: Burgen, Kirchenburgen, Stadtmauern um Bamberg, Bayreuth und Coburg, Fachverlag Hans Carl GmbH, Nuremberg, 2002, ISBN 3-418-00387-7, pp. 100–102.

- Toni Eckert, Susanne Fischer, Renate Freitag, Rainer Hofmann, Walter Tausendpfund: Die Burgen der Fränkischen Schweiz: Ein Kulturführer. Gürtler Druck, Forchheim, 1997, ISBN 3-9803276-5-5, pp. 115–120.

- Björn-Uwe Abels, Joachim Zeune, u.A.: Führer zu archäologischen Denkmälern in Deutschland, Band 20: Fränkische Schweiz. Konrad Theiss Verlag GmbH und Co., Stuttgart, 1990, ISBN 3-8062-0586-8, pp. 213–215.

- Gustav Voit, Walter Rüfer: Eine Burgenreise durch die Fränkische Schweiz, Verlag Palm und Enke, Erlangen, 1984, ISBN 3-7896-0064-4, pp. 142–145.

- Hellmut Kunstmann: Die Burgen der östlichen Fränkischen Schweiz. Kommissionsverlag Ferdinand Schöningh, Wurzburg, 1965, pp. 324–343.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pottenstein Castle. |

- Pottenstein Castle at Burgenwelt.de

- Home page of Pottenstein Castle

- Foracheim: history and images of Pottenstein Castle

- Home page of Pottenstein

- Pottenstein Castle on the home page of the House of Bavarian History (plans, history, construction history, condition)

- Artist's impression of the castle in mediaeval times