Portrayal of Mormons in comics

The portrayal of Mormons in comics includes anti-Mormon political cartoons from the 19th and 20th centuries as well as characters in comics who identify as Mormon. In addition, various artists have made comic book versions of parts of The Book of Mormon.

Early woodcuts from the 1840s depicted Mormons negatively in anti-Mormon literature. In the latter half of the 19th century, political cartoons satirized Mormon issues and events like the Mountain Meadows massacre, polygamy, and the death of Brigham Young. In these political cartoons, Mormons were often portrayed as an ethnic minority. Beginning in 1898 when B.H. Roberts was elected to congress and continuing through Reed Smoot's election to Senate, political cartoons focused on these politicians' ties to Mormonism and polygamy. After Smoot's hearing ended in 1904, cartoons about Mormons were less frequent.

20th-century Mormon comics have some references to Mormons, usually in passing as a cultural reference. Contemporary comics like Salt City Strangers and Stripling Warrior focus on the experiences of Mormon characters.

Various artists have depicted parts of The Book of Mormon in comic book form. In 1947, John Philip Dalby and Henry Anderson both published comics summarizing Book of Mormon stories. Ric Estrada's "Peace with Honor" fill-in story of Coriantumr was published in GI Combat #169 and his illustrations appeared in the LDS church's New Testament Stories in 1980. Mike Allred published three volumes of The Golden Plates in 2004 and 2005, which also summarizes events in The Book of Mormon. Other artists have attempted similar projects. Several events from LDS church history are also depicted in comics.

Portrayal of the early LDS Church in comic art

Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), also referred to as Mormons, have long been a subject of satirical humor. Illustrated anti-Mormon books and newspaper columns were commonplace throughout the United States during the 19th century.[1]:3–6

Woodcuts

Some of the earliest forms of illustration used to poke fun at the LDS faith were the woodcuts done by Eber D. Howe. He used these cuts published in 1834 to depict tall tales surrounding the account of Joseph Smith's acquisition of the golden plates.[1]:11 The next major anti-Mormon publication was done in 1842 and was an exposé turned book called History of the Saints, written by ex-Mormon John C. Bennett with woodcuts by F.E. Worchester and an illustration by Reverend Henry Caswall.[1]:12–13 In 1842, Sidney Roberts published Great Distress and Loss of American Citizens in which two prints, "A Partial View of the Massacre of the Mormons" and "Mormon's leaving the city of Nauvoo, February 1st, 1846", depicted the plight of the Mormons. Soon after, more ex-Mormon publications appeared, such as An Authentic History of Remarkable Persons. As the woodcuts were not used as often, by 1847 caricatures had become more prevalent and were used to portray the Council of the Twelve Apostles in a book written by ex-Mormons Maria and Increase Van Deusen. Their book went through twenty-three editions during an eighteen-year period and focused on aspects of temple worship and ceremonies sacred to the Mormons and included a detailed, fold-out illustration with color.[1]:14–16

Print from an early anti-Mormon book depicting Mormon temple clothes and Joseph Smith inaccurately.

Print from an early anti-Mormon book depicting Mormon temple clothes and Joseph Smith inaccurately. Print from an early anti-Mormon book with the subtitle "The Spiritual Wife."

Print from an early anti-Mormon book with the subtitle "The Spiritual Wife." Anti-Mormon illustration of the inner workings of the early Mormon temple from the Deusens's Spiritual Delusions.

Anti-Mormon illustration of the inner workings of the early Mormon temple from the Deusens's Spiritual Delusions.

In newspapers 1857–1898

In 1857, the first Mormon serial cartoons, later known as comics, emerged as part of Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper and bridged the subject of how women in the Mormon militia would affect the outcome of the Utah War.[1]:23 Other comics published that year focused on the Mountain Meadows massacre, depicting Mormons as people who were ignorantly obedient to a cruel prophet.[2] The following year another serial cartoon appeared in Nick Nax and portrayed the family and gender dynamics in the Mormon community. The most prevalent topic for Mormon criticism in the media during this time period surrounded the newly adopted practice of plural marriage.[1]:34 The illustrations entitled "Brigham Young the Great American Family" in Frank Leslie's Budget and "The Family Bedstead" in Roughing It, published in the 1870s, both satirised Mormon polygamy.[1]:38–40 In 1872 a ten-panel serial cartoon in Leslie's Weekley depicted a scene in which many Mormon women sought a Japanese ambassador's hand in marriage, entitled "The Adventures of the Japanese Ambassador in Utah".[1]:38[1]:38–40 Animalistic depictions of polygamy were also common. One example is The Lantern's depiction of a rooster surrounded by many hens with the caption "A foul (fowl) piece of Mormonism".[2]

Young's announcement of the implementation of the United Order in 1874 gave rise to another wave of satirical cartoons. Most of these were related to the illustrated periodical entitled Enoch's Advocate printed by anti-Mormons in Utah.[1]:42 The Beecher-Tilton Scandal Case of 1875 inspired a resurgence of Mormon-related comics. Although this adultery case was not directly related to Mormonism, for a few years following Young's death in 1877, the magazine Puck and other print sources related that Beecher was qualified to be his successor as president of the LDS Church.[1]:95–101

During the rest of the 1870s and continuing during the 1880s, most of the comics relating to Mormonism had ties to politics. One example depicts the many difficulties that the newly elected President Cleveland would face during his presidency in the comic from Puck entitled "Foes in His Path.-The Herculean Task Before Our Next President." These problems were illustrated and the typical personification of Mormonism, which included an old bearded man with the word Mormonism written around his waist and some depiction of his many wives, was shown among them.[1]:117

Brigham Young and other men are shown preparing their wives for war, 1857.

Brigham Young and other men are shown preparing their wives for war, 1857. 1858 cartoon depicting Mormon women attending soldiers.

1858 cartoon depicting Mormon women attending soldiers. 1858 cartoon depicting fictional officers in the Mormon army.

1858 cartoon depicting fictional officers in the Mormon army. 1869 cartoon: "Female suffrage: Wouldn't it put just a little too much power into the hands of Brigham Young, and his tribe?"

1869 cartoon: "Female suffrage: Wouldn't it put just a little too much power into the hands of Brigham Young, and his tribe?" 1871 cartoon of Young with his many wives and children.

1871 cartoon of Young with his many wives and children. 1872 cartoon of the Japanese ambassador visiting Utah meeting Young's wives and children.

1872 cartoon of the Japanese ambassador visiting Utah meeting Young's wives and children.

Mormons and racial minorities

In 1879, The Wasp introduced the comparison of the Mormons with other groups such as Chinese, blacks, Native Americans, and Irish peoples in a cartoon portraying Uncle Sam kicking said groups out of his bed.[1]:75 Many similar cartoons depicting Uncle Sam and his annoyance with the diverse religious and ethnic groups that resided in the United States were created during this period.[1]:81 Another way in which the media portrayed Mormons was by combining aspects of the Mormon and Catholic faiths, such as dressing a Mormon man in the religious clothing of the Catholic faith.[1]:84 Many times blacks were portrayed in Mormon polygamist families.[1]:85

According to historian W. Paul Reeve, by the early 1900s, with the intense media coverage of the Reed Smoot hearings, such images became "part of an effort to trap Mormons in a racially suspect past even as Mormon leaders attempted to shape a whiter future." Mormons were keenly aware of the racial slight:

Outsiders suggested that Mormons were physically different and racially more similar to marginalized groups than they were to white people. Mormons responded with aspirations toward whiteness. It was a back-and-forth struggle between what outsiders imagined and what Mormons believed. The process was never linear and most often involved both sides talking past each other. Yet, Mormons in the nineteenth century recognized their suspect racial position.

— W. Paul Reeve, in Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness (Oxford University Press, 2015)[3]

In newspapers 1898–1909

Between 1905 and 1909, The Salt Lake Tribune included over 600 cartoons relating to Mormonism.[1]:57 Related images were beginning to be produced in not only newspapers and magazines, but in pamphlets, periodicals, and more illustrated books. The Mormon leader and politician B. H. Roberts was elected to Congress in 1898, which put the LDS church in the spotlight once again and the fact that Roberts practiced polygamy caused many problems for him, his family, and the other Mormons still engaged in polygamist relationships. The Salt Lake Tribune and many other media outlets had a field day after discovering that one of Roberts' plural wives had just given birth to twins.[1]:61

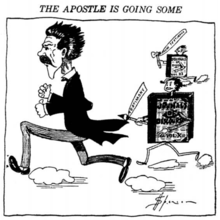

A similar reaction occurred in the press when Reed Smoot was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1903.[1]:65 For the next three years, many cartoons and comics were created surrounding Smoot's office.[1]:65 One of the most iconic of these sketches was "What They Expected at Washington" created by the cartoonist Lovey, which shows a train with one car for husbands, many more cars for wives, and then continuing off into the distance are the train cars full of Mormon children.[1]:65–66 The anti-Mormon sentiment in The Salt Lake Tribune was fueled by its owner, Republican senator Thomas Kearns.[4] Although Kearns and Smoot were initially friendly, according to Michael Paulos, Smoot's political success came a cost of Kearns's, and Kearns hired ex-Mormon Frank J. Cannon to edit the Tribune. Cannon's extreme anti-Mormonism, as reflected in the Tribune at the time, was noted sarcastically by non-Mormons: "How proud we Gentiles are of our self-constituted champions in the fight the Tribune is making on the Mormons!"[4]

.jpeg)

In 1904, after Smoot was officially seated in the Senate, the national media's intense interest in Mormonism slowly declined and because of new forms of communication and transportation people were able to learn more about the Mormons on a personal level instead of relying on the information provided in the comics of the daily newspaper.[1]:71

Many popular comic depictions included Mormon women who were impoverished, uncultured, hideous, unfaithful, overbearing, and overworked slaves to their husbands. They were also often depicted as being members of a harem and being part of a lustful marital lifestyle.[1]:127–128 During this time in history most women were portrayed in a negative light in the media, but because of the controversy of polygamy in Mormon culture, the amount of ridicule that Mormon women received was far worse than that received by their non-Mormon counterparts.[1]:136

Mormon characters in comics 1950s–today

Comic book adaptations of Sherlock Holmes's A Study in Scarlet were among the first portrayals of Mormons in comics.[5] The first comic book adaptation of A Study in Scarlet was in Classic Comic's 33rd issue, drawn by Louis Zansky. Zanksy's adaptation did not feature Mormons prominently, but the 1953 version of the story by Seymour Moskowitz did. A 1995 adaptation by Ricard Longaron Une etude en rouge and a 2010 adaptation by Ian Edgington and N. J. Culbard also depict Mormons as manipulative.[6] Mormons are also negatively portrayed in Chick Publications's small 1984 comic booklet "The Visitors" in which two Mormon missionaries fail to convert their investigator when the investigator's niece asks them about more controversial Mormon doctrines.[6]

The popular Italian comic book series Tex Willer, set in the American West, mentions Mormons, Danites, and the Mountain Meadows massacre.[6]

Other portrayals of Mormons in comics are references to current events or places. Published in the 1970s, issue #23 of Howard the Duck contains a duo who parody Don and Marie Osmond called the Dearth Vapors, who suffocate their opponents with the sweetness that comes out of their mouths.[7] "Godzilla, King of Monsters" #13 depicted Godzilla and another monster leaving the Salt Lake temple in ruins on the cover. In the actual comic, the temple was not destroyed.[7] In a Captain America comic book published in 1980 in issue #246, Joe Smith seeks revenge on Martin Harris for the death of his son, Joseph Smith Jr. While Joseph Smith Sr. never tried to kill Martin Harris, the names and situation are inspired by Mormon history.[7]

Some characters in comic books are Mormon to add interest to their character. A Kickstarter-funded comic, Salt City Strangers, follows five superheroes who explore Mormonism in different ways; none of the creators themselves are Mormon.[8][7] The series draws on local history and legends, with characters like "the gull" (a reference to the Miracle of the gulls) and "Den Mother" (a name for a women who leads cub scouts).[9] Stripling Warrior's superhero is a gay Mormon. Artist James Neish said he wanted "to show that a gay character is every bit as worthy in the eyes of God as any heterosexual one."[10] Writer Brian Anderson said that the series was based on his own experiences as a gay Mormon.[11]

In the alternate-history Captain Confederacy comic, Dr. Deseret is a Mormon who boldly contradicts polygamous Mormon men and suffers from an addiction to performance-enhancing drugs. A Mormon police detective, Jacob Raven, appears in Spider-man: The Lost Years. Mallory Brook, a Mormon lawyer in the same law firm as She-Hulk, is a prominent character in the series.[7][12]

Comics by Mormon artists

Versions of the Book of Mormon in comics

John Held Sr. (father of John Held Jr.) contributed illustrations to the 1888 The Story of the Book of Mormon.[13]

John Philip Dalby published an unfinished comic version of the Book of Mormon published in the Deseret News starting in 1947. Strips filled a full newspaper broadside. Publication was sporadic after 1948, and the last strip was published in 1953. Dalby followed the Book of Mormon chronologically; he started his series in Ether and covered 1 Nephi through 3 Nephi 16.[14] Herald Publishing House, owned by the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, also published a pictorial version of the Book of Mormon in 1947. The book by Henry Anderson was called The First Americans and summarized the Book of Mormon.[6]

Ric Estrada wrote a fill-in story for DC's GI Combat in #169 called "Peace with Honor," which recounted a Book of Mormon story where Shiz and Coriantumr battle to the death.[6] Mormon missionaries used a page from the story to teach potential converts about the gospel,[7] and in 1980, Estrada illustrated New Testament Stories for the LDS Church.

In the 21st century, several artists have tried their hand at adapting Book of Mormon stories to comics. In 2004 and 2005 Mike Allred created and published The Golden Plates, a three-volume, twelve-part comic book series that covers the Book of Mormon events from First Nephi to the Words of Mormon.[6] His wife Laura Allred colored the comics. The series is unfinished and out of print.[15] A unique aspect of these comics is the presence of Mormon women who are portrayed as being hard-working and intelligent. Nephi's wife is shown at his side during most of the text, which gives her a clearer role than that shown in the Book of Mormon itself.[16] In 2009, Micah Acker published a comic book volume Nephite Nation, which contains the story of Ammon.[17] Stephen R. Carter, editor of Sunstone and artist Jett Atwood published two volumes of Book of Mormon comics in 2012 and 2015 respectively, telling stories from the Book of Mosiah.[18] Also in 2012, Michael Mercer published From the Dust, the beginning of what was to be an ambitious retelling of the Book of Mormon, but the project was halted in 2014 due to a lack of marketing funds.[19]

Mormon history in comics

In 1948, Deseret Book Company published Blazing the Pioneer Trail with text by Floyd Larson and illustrations by Forrest Hill. The comic booklet contained a faithful account of the Mormon migration in 1847. Eileen Chabot Wendel also published comic book episodes from the Book of Mormon in her Stories from the Golden Records.[6] Ric Estrada wrote and illustrated Mormon material for DC Comics in his story "The Mormon Battalion" in No. 135 of Our Fighting Forces. Sal Velluto, an artist who has worked for DC and Marvel, was an art director for The Friend.[6] In his Blammo #7, published in 2011, Noah Van Sciver portrays the First Vision, the Angel Moroni visiting Smith, and the publishing of the Book of Mormon.[20]

See also

References

- Bunker, Gary L.; Bitton, Davis (1983). The Mormon Graphic Image, 1834–1914. Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah Press. ISBN 0874802180.

- Bunker, Gary L.; Bitton, Davis (1975). "Illustrated Periodical Images of Mormons" (PDF). Dialogue Journal. 10 (3): 82–92.

- W. Paul Reeve (2015). Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness. Oxford University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-19-975407-6.

- Paulos, Michael (2006). "Political Cartooning and the Reed Smoot Hearings" (PDF). Sunstone: 36–40.

- Harmer, Katie (September 10, 2013). "Brigham Young, Porter Rockwell and other Mormons in comics". Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- Homer, Michael W. (September 2010). "The Mormon Image in Comics" (PDF). Sunstone: 68–73. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- Mann, Court Mann (October 24, 2016). "As it turns out, Mormons and comic books have a long history together". Daily Herald. Retrieved October 26, 2016.

- "FAQ – Salt City Strangers". Salt City Strangers. Retrieved October 26, 2016.

- Springer, Alex (April 20, 2014). "FanX 2014: Chris Hoffman talks Salt City Strangers". SLUG Magazine. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- Nichols, JamesMichael (January 24, 2016). "Meet The World's First Gay Mormon Superhero". The Huffington Post. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- Allen, Samantha (January 31, 2016). "This World Needs This Gay Mormon Superhero". The Daily Beast. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- "Book, Mallory – Marvel Universe Wiki: The definitive online source for Marvel super hero bios". marvel.com. Marvel. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- Nelson, Glen (September 2010). "Jazz-Age Cartoonery: John Held, Jr. and the New Yorker" (PDF). Sunstone (160): 2–5. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- Parshall, Ardis (September 2010). "John Philip Darby: Musician, Storyteller, Artist" (PDF). Sunstone (160): 54.

- Weigel, David (October 11, 2011). "The Book of Mormon, Superhero-style". Slate. Archived from the original on March 5, 2013.

- Austin, Colin (2006). "Re-imagining Nephi" (PDF). Dialogue Journal. 39 (4): 251–254.

- "Acker Illustration Action Comics". www.mormonlink.com. MormonLink.com. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- "Second iplates offers another Book of Mormon graphic novel". Standard-Examiner. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- Mercer, Michael. "From the Dust". Mike's Crazy Ideas. Archived from the original on July 13, 2017. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- Jepson, Theric. "Two New Comics". www.motleyvision.org. A Motley Vision. Retrieved February 1, 2017.