Porc-Epic Cave

Porc-Epic Cave (also Porc Epic Cave, Porc-Épic Cave) is an archaeological site located in Dire Dawa, Ethiopia. Dated back to the Middle Stone Age, the site contains extensive evidence of microlithic tools, bone, and faunal remains. The lithic assemblage reveals that inhabitants at the time were well-organized with their environment. There is also rock art and strong evidence for ochre processing. The site was first discovered in 1920 by H. De Monfreid and P. Teilhard De Chardin. H. Breuil and P. Wernert performed the first excavation in 1933, followed from 1974 to 1976 by J. Desmond Clark and K.D. Williamson. Succeeding this was an excavation in 1998.[1] Porc-Epic Cave provides insight into the behavior and technical capability of modern humans in eastern Africa during the Middle Stone Age.

| Porc-Epic Cave | |

|---|---|

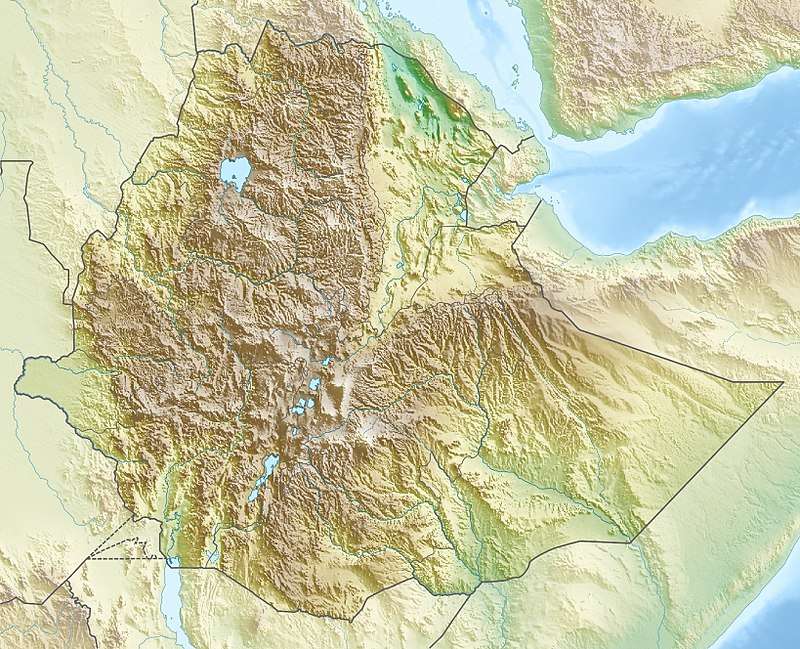

location of Porc-Epic Cave | |

| Coordinates | 9.5715°N 41.8874°E |

Geographical, environmental, and geological features

Geography

Porc-Epic Cave is a Middle Stone Age site located between the Somali Plateau and Afar Depression. It is also situated two kilometres northeast of Babo Terara and lies three kilometers south of Dire Dawa, Ethiopia. Sitting 140 meters above the wadi Laga Dächatu, it is near the top of the Garad Erer hill. The cave opens at the base of a Upper Jurassic limestone cliff.[2]

Environment

At the time of occupation, the Porc-Epic area was a grassland-dominated habitat. The presence of faunal remains from water-dependent animals, such as the reduncines and Syncerus caffer, imply that there was a source of water close to the site. The springs of La¨ga¨dol or La¨ga¨harre´ were likely used by occupants and animals, as well as the Da¨chatu River. The Da¨chatu River, however, is now active only during the rainy seasons. Located on a steep slope, Porc-Epic provides a wide view of the surrounding valleys. Residents may have utilized the broken valley surrounding the cave when hunting.[3]

Stratigraphic history

Porc-Epic Cave was formed by solution and collapse. Within the first phase, calcareous clay and sand formed through stream activity. The vesicular structure and faecal pellets are evidence that termites were active in the cave at the time. In the second phase, the calcareous clay moved upwards which formed cave breccia and limestone rubble. The third phase contained the MSA artifacts within the cave breccia. Beneath the breccia and dripstone were three transitional flow-stone horizons. Only the lowest contained fossil bones and artifacts. During the fourth phase dripstone formed and sealed the previous level. Artifacts were not present at the time and the cave was likely abandoned as it was too wet for occupation. The cave became drier in the sixth phase and dripstone formation came to halt. Occupation in the cave resumed in the seventh phase during prehistoric times. The cave formation overlaid the older deposits while carrying both microliths and pottery. The cave paintings are also attributed to this layer. Excluding the entrance, the cave is stratigraphically distinct.[4]

Archaeological history

Excavations 1933 to 1976

H. Breuil and P. Wernet undertook the first excavation in 1933 and largely focused on the entrance of the cave. Throughout this excavation, there was an abundance of obsidian and basalt artifacts. The Later Stone Age artifacts included 27 potsherds and a microlithic assemblage. A human jaw fragment was also uncovered and described as having both Neanderthal and non-Neanderthal features.[4] Throughout 1974 to 1976 most of the cave was excavated by J. Desmond Clark and K.D. Williamson. A collection of stone tools was recovered and accounted for over 90% of the total material extracted from the cave. Thousands of faunal artifacts were successfully excavated as well.[5] A total of 5146 artifacts were discovered during the series of excavations. On the basis that fauna was uncovered along with the lithic assemblage, the excavators of the site concluded that Porc Epic was a seasonal hunting camp during the fall and/or spring.[6] In 1998, a collaborative project took place between the French MNHN and Authority for Research and Conservation of Cultural Heritage (ARCCH) of Ethiopia concerning fieldwork on the site.[1]

Significance

Archaeological evidence

Ochre processing and rock art

Ochre processing is the grinding and flaking of ochre that results in fine-grain and powder.[7] Residue of the ochre was found in a variety of limestone, sandstone, granitoid and quartet tools. The residue suggests unintentional staining, whether it met contact with ochre powder or a person with stained hands. The brownish-yellow or red pigment that was produced is often used in prehistoric artwork. Rock art has been identified on the cave walls and studies reveal that the art is "older than the formation of the most recent stalagmite of the archaeological levels.”[2] While substantively faded, the paints are described as having a schematic style.[4] Porc-Epic inhabitants used different rocks for their grindstones. Grindstones made of soft rocks such as limestone produced a lighter powder. Grindstones made of hard rocks, like basalt, results in little particles derived from the tool. This suggests that the variety of rock types used for grindstones was based upon the inhabitants' needs. Differences in consistency, color and granulometry could be related to its purpose. Fine ochre powder, compared to rougher, is more suitable for cosmetic use such as body painting. Mixed grain size ochre would have been utilized in activities such as hafting. The use of different raw materials among grinding tools indicate that ochre was processed in the cave to perform a variety of activities and possibly served as a symbolic use. [8]

Tool making

Tools at Porc-Epic primarily consists of flakes and blades. Though the purpose of the tools are vague, the assemblages are predominantly of retouched points.[9] Shaped tools compromised 4% of the lithic assemblage while 88% of the shaped tools were points and scrapers.[4] Pointed tools indicate that the cave served as a hunting camp during seasons that game was plentiful.[4] Other tools display linear impressions which imply they were used as a retoucher through scraping and strikes against lithic edges. Diversified rock types were used for tools in Porc-Epic, as the diversified nature indicates that they were gathered through local and non-local means. Some tools indicate that the material was retrieved when venturing the landscape or through trade with neighboring groups.[2]

Obsidian

Obsidian is a favored material for stone tool production and its movement can be traced from an archaeological site to the source. The dominating material found during the excavations was chert, however, obsidian artifacts constitute 5.5% of total lithic assemblage. There is no immediate obsidian outcrop near the site, therefore, the excavators during the 1974 excavations hypothesized that the material was obtained from afar. Years later, a chemical analysis of the obsidian revealed three originating sources: Assebot, Kone, and Ayelu. Ayelu is situated near the town of Gewane, at 150 km north-west of Porc-Epic. Assebot lies within a similar distance and Kone rests 250 km to the west. The results support the previous claim that the material was not native to the site. Instead they were transported from long-distance areas.[6]

Faunal and human remains

A number of faunal remains have been uncovered at Porc-Epic cave. A taphonomic analysis revealed that humans were primarily responsible for the faunal carcasses and bone accumulation in the cave.[1] While some researches were unable to identify some specimens, the remaining varied from small to large mammals. Skeletal fragments such as hares, hyraxes, zebras, gazelles, and a buffalo were excavated. Small tooth marks and teeth were attributed to small rodents. Human bone remains include a mandible. What lacks in skeletal remains, evidence of human habitation lies in tools, paintings, and animal carcasses. The large assemblage of faunal evidence implies early humans accumulated the prey from other areas. The high location of the cave made it unsuitable for a kill site.[3] The remains provide insight of the foraging behavior of the early humans in the region.

Symbolic innovation

Hundreds of opercula of the terrestrial gastropod Revoilia guillainopsis have been produced at Porc-Epic. The opercula has a central perforation that resembles disc beads when unbroken. Their presence did not occur through natural processes nor were they a food source. The opercula instead held symbolic importance, as archaeological context suggests they were used as beads. However, it is unknown if they were manufactured as so or if it occurred naturally.[10]

References

- Pleurdeau, David (2005-12-01). "Human Technical Behavior in the African Middle Stone Age: The Lithic Assemblage of Porc-Epic Cave (Dire Dawa, Ethiopia)". African Archaeological Review. 22 (4): 177–197. doi:10.1007/s10437-006-9000-7. ISSN 1572-9842.

- Rosso, Daniela Eugenia; d'Errico, Francesco; Zilhão, João (2014-09-01). "Stratigraphic and spatial distribution of ochre and ochre processing tools at Porc-Epic Cave, Dire Dawa, Ethiopia". Quaternary International. Changing Environments and Movements through Transitions: Paleoanthropological and Prehistorical Research in Ethiopia A Tribute to Prof. Mohammed Umer. 343: 85–99. Bibcode:2014QuInt.343...85R. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2013.10.019. ISSN 1040-6182.

- Assefa, Zelalem (2006-07-01). "Faunal remains from Porc-Epic: Paleoecological and zooarchaeological investigations from a Middle Stone Age site in southeastern Ethiopia". Journal of Human Evolution. 51 (1): 50–75. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.01.004. ISSN 0047-2484. PMID 16545861.

- Clark, J. Desmond; Williamson, Kenneth D.; Michels, Joseph W.; Marean, Curtis A. (1984-12-01). "A Middle Stone Age occupation site at Porc Epic Cave, Dire Dawa (east-central Ethiopia)". African Archaeological Review. 2 (1): 37–71. doi:10.1007/BF01117225. ISSN 1572-9842.

- Pleurdeau, David (2005-10-25). "The lithic assemblage of the 1975-1976 excavation of the Porc-Epic Cave, Dire-Dawa, Ethiopia. Implications for the East African Middle Stone Age". Journal of African Archaeology. 3 (1): 117–126. doi:10.3213/1612-1651-10040. ISSN 1612-1651.

- Negash, Agazi; Shackley, M. S. (2006). "Geochemical Provenance of Obsidian Artefacts from the Msa Site of Porc Epic, Ethiopia*". Archaeometry. 48 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.2006.00239.x. ISSN 1475-4754.

- Rosso, Daniela Eugenia; d’Errico, Francesco; Queffelec, Alain (2017-05-24). "Patterns of change and continuity in ochre use during the late Middle Stone Age of the Horn of Africa: The Porc-Epic Cave record". PLOS ONE. 12 (5): e0177298. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1277298R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0177298. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5443497. PMID 28542305.

- Rosso, Daniela Eugenia; Martí, Africa Pitarch; d’Errico, Francesco (2016-11-02). "Middle Stone Age Ochre Processing and Behavioural Complexity in the Horn of Africa: Evidence from Porc-Epic Cave, Dire Dawa, Ethiopia". PLOS ONE. 11 (11): e0164793. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1164793R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0164793. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5091854. PMID 27806067.

- Leplongeon, Alice (2014-09-01). "Microliths in the Middle and Later Stone Age of eastern Africa: New data from Porc-Epic and Goda Buticha cave sites, Ethiopia". Quaternary International. Changing Environments and Movements through Transitions: Paleoanthropological and Prehistorical Research in Ethiopia A Tribute to Prof. Mohammed Umer. 343: 100–116. Bibcode:2014QuInt.343..100L. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2013.12.002. ISSN 1040-6182.

- Assefa, Zelalem; Lam, Y. M.; Mienis, Henk K. (2008-08-01). "Symbolic Use of Terrestrial Gastropod Opercula during the Middle Stone Age at Porc‐Epic Cave, Ethiopia". Current Anthropology. 49 (4): 746–756. doi:10.1086/589509. ISSN 0011-3204.