Pontcallec conspiracy

The Pontcallec conspiracy was a rebellion that arose from an anti-tax movement in Brittany between 1718 and 1720. This was at the beginning of the Régence (Regency), when France was controlled by Philippe II, Duke of Orléans during the childhood of Louis XV. Led by a small faction of the nobility of Brittany, it maintained links with the ill-defined Cellamare conspiracy, to overthrow the Regent in favour of Philip V of Spain, who was the uncle of Louis XV. Poorly organised, it failed, and four of its leaders were beheaded in Nantes. The aims of the conspirators are disputed. In the 19th and early 20th century it was portrayed as a proto-revolutionary uprising or as a Breton independence movement. More recent commentators consider its aims to have been unclear.

Background

In 1715, after Louis XIV died, France was heavily in debt after many years of war. Feeling unfairly taxed, the Estates of Brittany gathered in Saint-Brieuc and refused to extend new credits to the French state. The Estates sent three emissaries to Paris to explain its position to the Regent. However, the Regent responded by sending Pierre de Montesquiou d'Artagnan to Brittany as representative of the King. Montesquiou decided to raise taxes by force.

The Regent decided to convene the Estates anew. On 6 June 1718, it assembled in Dinan. It was dominated by the gentry, the composition of which was very different from the rest of France, since a significant proportion of the population were counted as "dormant nobles". This concept allowed noble status, and consequent political rights and exemptions, even among the poor if they could prove noble ancestry. In some areas the overwhelming majority of "nobles" were living in poverty.[1] The Estates resisted new taxation arrangements that threatened the poorer nobles. Exasperated by the taxes, the lesser nobles dreamed of an aristocratic republic. On 22 July 1718, 73 of the more radical delegates to the Estates were exiled.[2]

Meanwhile links were established with Philip V of Spain and the Duke and Duchess of Maine, who were conspiring to overthrow the Regency which had originally been promised in Louis XIV's will to the Dukes of Maine and Orleans jointly. Louis-Alexandre de Bourbon, comte de Toulouse, who was also Duke of Penthièvre and thus a Breton aristocrat, liaised with the Duke of Maine.

The conspiracy

On 26 August 1718, a ruling prevented the Duke of Maine from taking advantage of the prerogatives granted by Louis XIV in his will, giving him a powerful incentive to overthrow the regency. Events unfolded rapidly; in Brittany it was rumored that the Duke of Maine wanted to recruit troops. Meanwhile an "Act of Union", a list of local grievances, was drawn up and signed by several hundred Breton nobles.[3] In September, the Count of Noyan, one of its authors, met with the Marquis de Pontcallec (1670–1720), a member of a well-known family and owner of a powerful fortress near Vannes. Along with a group of radicals Pontcallec hoped to organise a rebellion. Recruitment of support began among the middle-class farmers and local smugglers, traditional clients of the nobility of Brittany.[2] When the War of the Quadruple Alliance between Spain and France broke out a Breton envoy was sent by Pontcallec's faction to the Spanish minister Giulio Alberoni.[2][3]

On 29 December 1718, the Duke and Duchess of Maine were arrested. Pontcallec pursued his plans and continued recruitment, while other aristocrats joined him. Threatened with being arrested for smuggling, he ordered a general meeting in Questembert which was attended by 200 supporters. However, no attempt to arrest him was made and the group dispersed. Nevertheless, the rally had been noted. In July, the Regent was informed.[4]

Meanwhile the Spanish offered support to overthrow the Regent and install in his place Philip V or the Duke of Maine. None of this was originally planned, but was accepted by Pontcallec. On 15 August, a group of peasants led by Rohan of Pouldu forced a group Royal soldiers sent to enforce tax collection to retreat. In September, Pierre de Montesquiou entered Rennes at the head of an army of 15,000 men. At the same time, one of the conspirators was arrested at Nantes where he confessed everything. Alerted, Pontcallec's supporters took refuge in his castle. However, Pontcallec failed to organize his defenses, and only a dozen people responded to his call for aid. On 3 October, the Regent established a Board of justice to try the conspirators.

Three frigates containing Irish troops were sent by the Spanish to Brittany. When the first ship landed it became apparent that the 2,000 troops sent would not be able to sustain a battle against the 15,000 strong Royal army without local support. The troops were reembarked, and some conspirators fled with them. Completely isolated, Pontcallec was betrayed and arrested on 28 December 1719. Seventy other participants were also detained.[4]

Trial

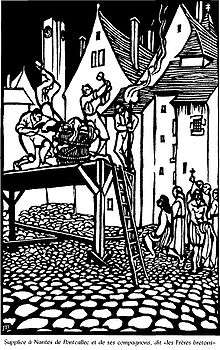

The trial occurred in Nantes. The Duchess of Maine confessed the existence of a plot against the Regency, which was to have been overthrown by inciting risings in Paris and Brittany with Spanish assistance. The Regent, Philip II, Duke of Orléans, along with the Abbé Guillaume Dubois and the financier John Law identified 23 key conspirators. 16 had escaped and were accused in absentia; 7 more were in custody (Pontcallec, Montlouis, Salarun, Talhouët, Du Couëdic, Coargan and Hire de Keranguen). 20 conspirators were found guilty and four of the seven in court were condemned to death: Pontcallec, Montlouis, Talhouët and Du Couëdic. Sixteen others were also condemned in their absence. The four condemned men were decapitated the same day, in the Place du Bouffay, Nantes.[2]

The verdict shocked contemporaries by its severity, since the rebellion had amounted to so little. The cost of the whole operation was also deemed excessive. However, soon afterwards the economic crisis brought about by the collapse of John Law's financial system overwhelmed such concerns. After the executions, the repression stopped. The government withdrew from its taxation demands, and confiscated monies and property were restored. Exiled conspirators were allowed to return to France after ten years.[2]

Aftermath and significance

The conspiracy of Pontcallec is noted for its ineffectiveness and the confused aims of its leaders. Only a small fraction of the Breton nobility in general took part and the Breton people as a whole were excluded since its professed intent was to defend the established rights and liberties of the nobility. Despite this the conspiracy quickly acquired legendary status in Brittany and Pontcallec's death turned him into a folk hero. Théodore Hersart de la Villemarqué discusses his actions in his historical notes to Barzaz Breiz (The Ballads of Brittany), in which he included a ballad Marv Pontkalleg (The Death of Pontcallec), praising "le jeune marquis de Pontcallec, si beau, si gai, si plein de cœur" (the young Marquis de Pontcallec, so handsome, so gay, so full of heart).[5] This song became very popular in Brittany, and has been recorded by Alan Stivell, Gilles Servat and Tri Yann.

Le Villemarqué's notes portray Pontcallec as a rebel who led a Breton independence movement supported by both the aristocracy and the people, stating that "the Bretons declared the act of union with France null" and that they had sought Spanish help to secure the "absolute independence of Brittany".[6] The interpretation was repeated by the Breton nationalist movement, which depicted him as a martyr: the Breton equivalent of Wolf Tone and Patrick Pearse. Arthur de la Borderie in La Bretagne aux Temps Modernes 1471-1789 (1894) stated that the rebellion was a legitimate reaction to a centralising and potentially despotic monarchy, adding that the names of the victims are "enrolled in the most glorious place in our martyrology ... it was the last blood spilt for the law, constitution and freedom of Brittany."[2][7] In Jeanne Coroller-Danio's Histoire de Notre Bretagne (1922) the conspiracy is presented as an heroic act of resistance to French oppression. In 1979 a plaque was placed at the site of the executions by Raffig Tullou's nationalist group Koun Breizh stating that "defenders of Breton liberty" were decapitated on the spot "by royal order".[2]

The Pontcallec Conspiracy is dramatized in Alexandre Dumas's novel The Regent's Daughter (1845), which tells the story of two lovers mixed up in the events of the conspiracy. It is also central to the 1975 film Que la fête commence (English title Let Joy Reign Supreme), directed by Bertrand Tavernier and starring Philippe Noiret as the Regent and Jean-Pierre Marielle as Pontcallec.

Notes

- Jean Meyer, La noblesse bretonne au XVIIIme siecle, Éditions de l'EHESS, Paris, 1995. In 1710 in Côtes-d'Armor, many nobles owned no land. In the diocese of Tréguier, 77% of nobles were named "misérables" (impoverished). In Saint-Malo, 55% of nobles were "misérables".

- Alain Tanguy, "La Conspiration de Pontcallec: un complot sépatatiste sous a Régence", ArMen, 2005, pp. 10-19, ISSN 0297-8644

- John Jeter Hurt, Louis XIV and the Parlements Manchester University Press p.180.

- Joël Cornette, Le marquis et le Régent. Une conspiration bretonne à l'aube des Lumières, Paris, Tallandier, 2008

- The "young Marquis" was in fact 49 years old at the time of his death.

- La Villemarqué, Thédore Hersart, Barzaz Breiz, Paris: Didier, 8th edition, 1883, p.326.

- French: inscrits au lieu les plus glorieux de notre martyrology...c'est le dernier sang verse pour la loi, la constitution et la liberte bretonnes.