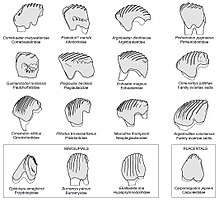

Plagiaulacoid

A plagiaulacoid is a type of blade-like, most often serrated, tooth present in various mammal groups, usually a premolar. Among modern species it is present chiefly on diprotodontian marsupials (specifically, Potoroidae, Bettongia and Burramys), which have both the upper and lower first premolars converted into serrated blades. However, various other extinct groups also possessed plagiaulacoids. These would be multituberculates, some "Plesiadapiformes" such as Carpolestes and various metatherians such as Epidolops and various early diprotodontians. In many of these only a lower premolar became converted into a blade, while the upper premolars showed less speciation.[1][2]

The various independent development of these teeth is considered a good example of convergent evolution.[3][4][5]

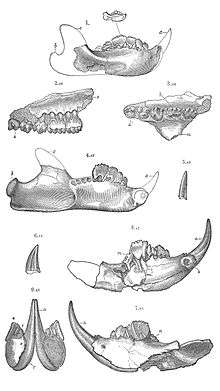

Multituberculates in particular probably own the most specialised of all plagiaulacoids. In early taxa, all lower premolars became plagiaulacoids, forming a "saw"-like arrangement. However, in Cimolodonta, premolars 1-3 degenerated and became peg-like or disappeared altogether; instead, only the fourth lower premolar remained, which increased in size. While earlier multituberculates displayed a normal tooth replacement for their plagiaulacoids, in cimolodonts this tooth was not replaced, being the last tooth to erupt and remaining through the animal's life.[6]

Function

Most taxa with plagiaulacoids are omnivores with granivore tendencies; as such, it is speculated that plagiaulacoid premolars evolved to help these mammals break or saw through tough seeds and other tough plant matter with precision, as well as to help manipulate food items in the mouth.[7][8] Modern diprotodontian marsupials often use their plagiaulacoids this way.[9]

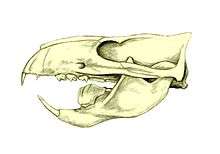

However, many groups with plagiaulacoids have animalivorous tendencies. Various Macropodiformes and multituberculates show evidence of insectivorous and carnivorous habits, and in the latter in particular the plagiaulacoids could have been very useful meat-slicing teeth. In kogaionids the plagiaulacoid exhibits the same iron-pigmentation as the rest of the other teeth, suggesting its use in break insect exoskeletons,[10] while multituberculate plagiaulacoid gnawing marks are known in Champsosaurus bones.[11] In marsupial lions the plagiaulacoids straight-up became carnassial teeth.

Secondary Loss

In various groups the plagiaulacoid was lost. In most cases, this is correlated to increased herbivory, especially grazing. In taeniolabidoids and some other cimolodonts the plagiaulacoid simply shrunk, while in gondwanatheres and kangaroos it reconverted back into a "normal" molar.[12]

References

- George Gaylord Simpson, The "Plagiaulacoid" Type of Mammalian Dentition A Study of Convergence George Gaylord Simpson Journal of Mammalogy Vol. 14, No. 2 (May, 1933), pp. 97-107 Published by: American Society of Mammalogists DOI: 10.2307/1374012 Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1374012

- Susan Cachel, Fossil Primates, Cambridge University Press, 23/04/2015

- George Gaylord Simpson, The "Plagiaulacoid" Type of Mammalian Dentition A Study of Convergence George Gaylord Simpson Journal of Mammalogy Vol. 14, No. 2 (May, 1933), pp. 97-107 Published by: American Society of Mammalogists DOI: 10.2307/1374012 Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1374012

- Susan Cachel, Fossil Primates, Cambridge University Press, 23/04/2015

- Kielan-Jaworowska, Zofia, Richard L. Cifelli, and Zhe-Xi Luo (2005). Mammals from the Age of Dinosaurs: Origins, Evolution, and Structure

- Kielan-Jaworowska, Zofia, Richard L. Cifelli, and Zhe-Xi Luo (2005). Mammals from the Age of Dinosaurs: Origins, Evolution, and Structure

- George Gaylord Simpson, The "Plagiaulacoid" Type of Mammalian Dentition A Study of Convergence George Gaylord Simpson Journal of Mammalogy Vol. 14, No. 2 (May, 1933), pp. 97-107 Published by: American Society of Mammalogists DOI: 10.2307/1374012 Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1374012

- Kielan-Jaworowska, Zofia, Richard L. Cifelli, and Zhe-Xi Luo (2005). Mammals from the Age of Dinosaurs: Origins, Evolution, and Structure

- Susan Cachel, Fossil Primates, Cambridge University Press, 23/04/2015

- Thierry Smith, Codrea Vlad, Red Iron-Pigmented Tooth Enamel in a Multituberculate Mammal from the Late Cretaceous Transylvanian " Haţeg Island ", Article in PLoS ONE 10(7):e0132550-1-16 · July 2015 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132550

- Mammalian tooth marks on the bones of dinosaurs and other Late Cretaceous vertebrates, First published: 16 June 2010 DOI: 10.1111/j.1475-4983.2010.00957.x

- Gurovich, Y.; Beck, R. (2009). "The phylogenetic affinities of the enigmatic mammalian clade Gondwanatheria". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 16 (1): 25–49. doi:10.1007/s10914-008-9097-3.