Pella, Jordan

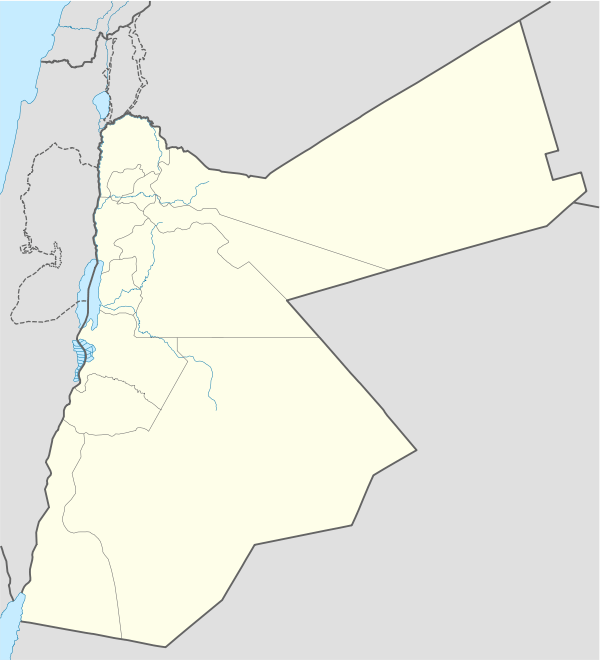

Pella (Greek: Πέλλα, Hebrew: פחל) is located in northwest Jordan at a rich water source within the eastern foothills of the Jordan Valley, close to the modern village of Ṭabaqat Faḥl (Arabic: طبقة فحل) some 27km (17 miles) south of the Sea of Galilee (Lake Tiberias). The site is situated 130 km (80 miles) north of Amman, a drive of about an hour and a half (due to the difficult terrain), and is a shorter half an hour by car from Irbid, in the north of the country. Today the city's ruins, predominately temples, churches and housing, have been partially excavated by teams of archaeologists, and attract thousands of tourists annually but especially in spring, during which time the area is awash with spring flowers.[1]

Πέλλα | |

Classical Pella, 2005. | |

Shown within Jordan | |

| Alternative name | Fihl, Tabaqat Fahl |

|---|---|

| Location | Irbid Governorate, Jordan |

| Region | Levant |

| Coordinates | 32°27′N 35°37′E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Site notes | |

| Ownership | Government of Jordan |

| Management | Department of Antiquities of Jordan |

History

Pella has been almost continuously occupied since Neolithic times.[2] Originally called Pihilum, the town was renamed "Pella" in the Hellenistic period after the birthplace of Alexander the Great, and with other like-minded towns in the region formed a political and cultural league known as the "Decapolis", an alliance that grew in stature and economic importance to became regionally influential under Roman jurisdiction [3]. However, Pella expanded to its largest size during the Byzantine period, when it was a bishopric in the province of Palaestina Secunda. In Islamic times, after 635 CE, the town became part of the Jund al-Urdunn (Province of Jordan), but in time was negatively impacted by natural calamities and eclipsed by the geo-political successes of the nearby towns of Amman, Beisan and especially Tabariyah (Tiberias).

Bronze and Iron Ages

The city was first mentioned in the 19th century BCE in Egyptian execration texts, and it continued to flourish throughout the Bronze Age.[4]

While the cause is not known, the dawn of the Iron Age meant the end of power in Pihilum. The urban heart of the Iron Age city-kingdom seems to have suffered a major destruction in the later 9th century, from which it did not recover.[5]

Hellenistic period

Re-established as an urban centre under the early Seleucids, its ancient name must still have been known, for its new, Greek name was a close synonym, Pella - the birthplace of Alexander the Great in Macedon.

As yet no public buildings from the Hellenistic period have been identified, although well-appointed private houses attest to their integration into the wider norms of urban living, such as wall-paintings and statuary. Several of these houses suffered what appears to be the same fiery destruction in the Late Hellenistic period. This has been attributed to a massive destruction by the Hasmonean king, Alexander Jannaeus, about 83 or 82 BCE (Josephus, The Jewish War 14.4.8; Antiquities 14.4.4). From Josephus, it is clear that Pella had been damaged and so needed some restoration by Pompey decades afterwards, but his specific reference to the destruction of Pella by Jannaeus because its inhabitants refusing to follow Jewish customs, seems to refer to a different place (Antiquities, XIII.395-397): it is listed as if amongst southern Levantine cities and out of its more normal sequence between Gadara, Gerasa and Scythopolis.

Roman period

In 63 BCE, the Roman General Pompey integrated the region into the Eastern portion of the Roman Empire, converting the old Seleucid empire into the province of Coele-Syria and incorporating Judaea as a client kingdom.[4] A group of cities claiming Greek Hellenistic foundations asked Pompey for freedom from the threat of incorporation within Rome's new client-state of Hasmonaean Judaea. Pompey agreed, and these cities were called the Decapolis[6] - literally, the ten cities - although the lists which have survived vary in composition and number. Pella, however, is consistently a "Decapolis" city, and the city in the northernmost bounds of the region known as Perea.[7] If these cities had previously dated their years from their foundation under Alexander the Great or Seleucis I Nicator, they now honoured Pompey by counting 63 BC as a new "Year One". Like most cities within the empire, Pella would have had its own town council. It also minted coins in the Roman period.

Pella was incorporated within Roman Judaean territory (Jewish Wars 3.5), which region was attacked by Scaurus during his Nabataean sortie (The Jewish War 1.8.1). Pella was one of eleven administrative districts (toparchies) in Roman Judea.[8] During the outbreak of the First Jewish-Roman War, when the Syrian inhabitants of Caesarea had slain its Jewish citizens, there was a general Jewish uprising against neighboring Syrian villages, who sought revenge for the murder of their countrymen, during which time Pella was ransacked and destroyed.[9] Growing Jewish dissent over Roman military occupation in Judea brought about Roman reprisals against Jewish enclaves in the regions of Galilee, the coastal plains of Judea, Idumea and Perea, until, at length, the Roman army had subdued all insurgents and their military governors established during the Jewish revolt.

First Christians: the "flight to Pella"

In what is known as the "flight to Pella", around the time of the Roman siege and destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE, tradition holds that a Jewish sect of Nazarenes made their way to Pella and settled in the city which became a Jewish Christian hub during the early days of Christianity.[10] According to Epiphanius, the disciples had been miraculously told by Christ to abandon Jerusalem because of the siege it was about to undergo.[11]

Epiphanius claims that after the destruction, some returned to Jerusalem.[12] Similarly to Epiphanius, Eusebius of Caesarea recounts how Pella was a refuge for Jerusalem Christians who were fleeing the First Jewish–Roman War in the 1st century CE.[13] Pella is alleged to have been the site of one of Christianity's earliest churches, but no evidence has been found of this. According to Historian Edward Gibbon, the early Church of Jerusalem fled to Pella after the ruin of the temple, staying there until their return during the reign of Emperor Hadrian, making it a secondary pilgrimage site for early Christians and modern Christians today.

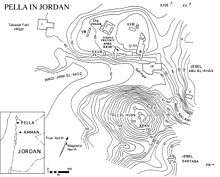

Byzantine period

In the late Roman and Byzantine periods, the town extended over the ancient tell, across the broad central valley of the town today known as the Wadi al-Jirm (see photograph), and over the slopes and summit of the southern hill known as Tell al-Husn. By the Byzantine era, Pella had reached its maximum size and, probably, prosperity. Being part of the province of Palaestina Secunda ("second Palestine"), it certainly had a bishop by the year AD 451. At least three triapsidal churches have been identified within the city: the West Church at the western foot of the tell; the Civic Complex church in the wadi al-Jirm at the SE foot of the tell and which, due to its size and location, was probably the cathedral; and the elevated East Church on the higher slopes of the Jebel Abu el-Khas.[14] On the tell, the entire summit was leveled off and a new gridded urban zone constructed during the time of the Byzantine emperor Justinian I. The access streets were lined with newly built shops and large buildings, serving both commercial and residential functions. This concern with urban development matched similar activities in other Decapolis towns, such as Gadara (Umm Qays) and Gerasa (Jerash/Jarash), and reflects the role of regional centres in serving local populations during late antiquity.

Islamic period

On the plain of the Jordan Valley below Pella, a historically decisive battle took place in January 635 CE (13 AH) between a Muslim army and the Byzantine forces stationed at Pella and Scythopolis (Beit She'an; Beisan). This encounter, one of the earliest between Muslims and Byzantines, came to be known as the Battle of Fihl (also Battle of Fahl, Fahl being a later variant of Fihl). The Muslims forces faced little resistance with the town of Pella surrendering by treaty, thereby avoiding occupation by military conquest. Accordingly, the archaeological record shows no disruption attributable to the arrival of Islam, as was the case for nearly all the towns of Bilad al-Sham.[15] Rather, the churches, markets and houses of Pella continued in use, with the archaeology showing their progressive modification to meet evolving social and political conditions, as in many of the other towns of the Decapolis alliance in north Jordan. In particular, a large market and workshop area was installed adjacent to the Civic Complex church at the heart of the Byzantine town plan.[16].

Pella, which by the eighth century CE had officially returned to its original Semitic name of Fihl (variant of Pihil), was totally devastated by the massive 749 Galilee earthquake, as a Jordan Valley rift fault line runs directly under the site. The stone and mudbrick two-storeyed houses on the top of the tell (main mound) collapsed in on themselves, thereby trapping the inhabitants — human and animal — and preserving a rich collection of finds sourced from distant regions, such as Egypt and the Arabian Peninsula [17]. Subsequent settlement at Pella, dated from the later eighth to eleventh centuries CE, was reduced in size, but featured an enclosed double-courtyard architectural complex in the valley immediately north of the tell.[18] The configuration of the complex suggests markets (khans), with commercial activities such as glass workshops. Occupation spans the Abbasid into Fatimid periods. Recent work on the tell has identified widespread rebuilding following the 749 earthquake, as indicated by wall foundations, plastered floors and refuse pits filled with finely worked bone and moulded glassware. Evidence for a presence in the Crusader period (12th century CE) is slight — a few pottery sherds only — but in the following Ayyubid and Mamluk periods the flat summit of the tell was inhabited by a large village, featuring a stone-built mosque with a minbar (pulpit), residential compounds defined by lane ways, and a large cemetery.[19]. Late 16th century Ottoman defters list a village called Fahl el Tahta in the administrative district of Ajlun where wheat, barley, and sesame were grown and taxes collected on goats, beehives and water-driven mills.[20]

Excavations

The site was first published as part of a regional survey by G. Schumacher,[21] but the first excavation was conducted by Funk and Richardson only in 1958, revealing Iron and Bronze Age material in two soundings.[22] From 1966-7, R. H. Smith led a team from Wooster College (Ohio) to prepare a plan of the site and its environs, and begin excavations, but was interrupted by the Six Day War.[23] A joint project with the University of Sydney (Australia), but with separate excavation teams and seasons, explored the city from 1978-1985. The Australian expedition was initially directed by Prof. J. B. Hennessy and Dr A. W. McNicoll. Wooster stopped excavations in 1985, but the Australian project continues.[24] Between 1994 and 1996, Pam Watson (at the time, Asst Director of the British Institute at 'Amman)and Dr Margaret O'Hea of the University of Adelaide conducted the Pella Hinterland Survey to identify land-use in an area approx. 30 square kms around the city.[25] More recently, the project under the director Stephen Bourke, the focus has been on the site's Bronze Age and Iron Age temples and administrative buildings.[26] A Canaanite temple was uncovered from 1994 to 2003.[27] In May 2010 Stephen Bourke announced the discovery of a city wall and other structures, dating back to 3400BC, indicating that Pella was a formidable city-state at the same time the cities of Sumer were taking shape.[28]

References

- "Pella, Jordan". www.atlastours.net. Retrieved 2015-11-29.

- Smith, Robert (July 1984). "Pella in Jordan 1". American Journal of Archaeology. 88 (3): 426–427. doi:10.2307/504582. JSTOR 504582.

- Graf, D.F. (1992) "Hellenisation and the Decapolis." ARAM 4(1): 1-48.

- Smith, Robert H. (1968). "Pella of the Decapolis 1967". Archeological Institute of America. 21 (2): 134–137. JSTOR 41667820.

- Bourke, S. (1997) Pre-Classical Pella In Jordan: A Conspectus Of Ten Years' Work 1985-1995. PEQ 129: 94-115.

- Rami G. Khouri, The Decapolis of Jordan, Saudi Aramco World, November/December 1985 print edition, pp. 28-35, via archive website, accessed 19 December 2019

- Josephus, The Jewish War 3.3.3. (3.44)

- Josephus, The Jewish War 3.3.5. (3.51)

- Josephus, The Jewish War 2.18.1. (2.457)

- Klijn, A.F.J.; Reinink, G.J. (1973). Patristic Evidence for Jewish-Christian Sects. Leiden: E.J. Brill. pp. 44–46. ISBN 978-9-00403763-2. (OCLC 1076236746)

- Epiphanius of Salamis (377). Panarion, or, Against the Heresies. p. book 29, 7:8. Archived from the original on 2015-09-06.

- Epiphanius. Treatise on Weights and Measures. Chicago University Press.

- Eusebius, History of the Church, 3.5.3

- McNicoll, A.W. et al. (1992) Pella in Jordan 2. The Second Interim Report of the Joint University of Sydney and College of Wooster Excavations at Pella 1982–1985, Chapter 8. Sydney: Mediterranean Archaeology.

- Pentz, P. (1992) The Invisible Conquest. The Ontogenesis of Sixth and Seventh Century Syria. Copenhagen: National Museum of Denmark.

- Walmsley, A.G. (1992) Fihl (Pella) and the Cities of North Jordan during the Umayyad and Abbasid Periods. Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan vol. 4: 377-384.

- Walmsley, A.G. (2007) Households at Pella, Jordan: the domestic destruction deposits of the mid-eighth century. In L. Lavan, E. Swift and T. Putzeys (Eds), Objects in Context, Objects in Use. Material Spatiality in Late Antiquity, 239-272. Leiden: Brill.

- Walmsley, A. et al., (1993) The Eleventh and Twelfth Seasons of Excavations at Pella (Tabaqat Fahl): 1989-1990. ADAJ, vol. 37: 165-240'

- S. McPhillips and A.G. Walmsley (2007), Fahl during the Early Mamluk Period: archaeological perspectives. Mamluk Studies Review 11(1): 119-156

- Hütteroth, W.D. and K. AbdulFattah (1977) Historical Geography of Palestine, Trans-Jordan and South Syria in the Late 16th Century, p. 167. Erlangen: Frankische Geographische.

- Schumacher, G. (1888) Pella. London: Palestine Exploration Fund. Reprinted in 2010

- Funk, R. and Richardson, H. (1958) The 1958 Sounding at Pella. The Biblical Archaeologist, 21.4:81-96.

- The results were published in Smith and Day, (1973) Pella of the Decapolis. Vol. 1, The 1967 season of the College of Wooster Expedition to Pella. Wooster, Ohio: College of Wooster.

- See the interim joint volume by McNicoll, et al. (1982) Pella in Jordan 1: an interim report on the joint University of Sydney and the College of Wooster excavations at Pella 1979-1981. Canberra: National Gallery of Australia. The final report was Smith et al.,(1989) Pella of the Decapolis, Volume 2: Final Report on the College of Wooster Excavations in Area IX, the Civic Complex, 1979-1985. Wooster, Ohio: College of Wooster. ''Pella in Jordan 2: The Second Interim Report of the Joint University of Sydney and College of Wooster Excavations at Pella, 1982-1985 (Meditarch Supp. 2) was published in 1992.

- Watson and O'Hea (1996), Pella Hinterland Survey 1994: Preliminary Report. Levant 28: 63-76; Watson, P. (2006) Changing Patterns of Settlement and Land Use in the Hinterland of Pella (Jordan)in Late Antiquity. Pp.171-192 in A. Lewin and P. Pellegrini (eds), Settlements and Demography in the Near East in Late Antiquity. Pisa: Istituti Editoriali e Poligrafici Internazional

- The Near Eastern Archaeology Foundation, University of Sydney: Pella

- Ben Churcher, The Discovery of Pella's Canaanite temple

- Jordan Times 31 May 2010: Jordan Valley - cradle of civilisations?

Adams, Russell Ed. (2008). Jordan: an archaeological reader. London, Equinox.

Sheedy, Kenneth A., R.A.G. Carson and Alan Walmsley (2001). Pella in Jordan 1979-1990: the coins. Sydney, Adapa.

Weber, Thomas (1993). Pella Decapolitana. Wiesbaden, Harrassowitz.