Piha Tramway

The Piha Tramway was from 1906 to 1921 a 3-foot (910 mm) narrow gauge forest railway in New Zealand, the steepest sections of which were operated on inclines by steam-powered cable winches.

| Piha Tramway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 3 ft (910 mm) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Route

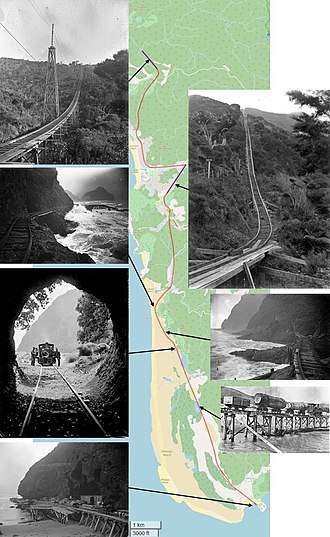

During the deforestation of the kauri forests in the Piha region, the logs had to be taken over a distance of eight kilometres (5.0 miles) to the sawmill in Karekare, New Zealand, and the sawn timber had to be transported from there for another eight kilometres (5.0 miles) along the coast to Whatipu, where it could be loaded onto ships.[1]

Before the railway was built, the wood was dragged by oxen or horses on the beach at low tide to Whatipu. Around 1906, Dr Raynor, a Canadian-born dentist working in Auckland, participated in William Stokes' timber extraction company, which had come into financial difficulties. Together they built a sawmill and a steam-powered forest railway. The wood was brought from the Piha Valley up to the steam-operated sawmill by a 1:4.5 (22%) steep incline and then to Karekare Beach by a 1:2.5 (40%) steep incline over a total distance of about 8 kilometres (5.0 miles).[1][2]

Over time, the forest railway was extended northwards to bring tribes from the nearby Anawhata Valley to Piha. Later, an approximately 8 km (5.0 mi) long narrow-gauge line was built in the south, following the route of another previously built forest railway. It led from Karekare along the Tasman Sea to Whatipu, where a new jetty had been built at the entrance to Manukau Harbour on the side protected by Paratuate Island.[1]

For the narrow-gauge railway with a gauge of 3 feet (0.91 metres), steel rails with a weight of 7 to 14 kg/m (14 to 28 lbs/yd) were laid on 125 mm × 50 mm (4.9 in × 2.0 in) wooden sleepers.[2] Most of the railway line along the Tasman Sea was of primitive quality. It crossed soft sandy beaches just a few metres above sea level and made its way along rocky outcrops and often past steep cliffs. Along the cliffs, where there was no natural route for the line, holes were drilled in the rock, in which the railway sleepers were fastened.[1]

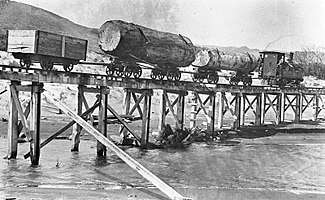

Both the construction and the operation were affected by the notorious West Coast weather: Storms, torrential rain, wind and sand blowing across the tracks. The crossing of Karekare Beach itself proved difficult. The sand was hard in some areas and soft in others. Some up to 5 m (16 ft) high, primitive trestle bridges were built where the cliffs were interrupted at estuaries or bays. A tunnel was built, of which the clearance outline was so narrow that the chimney of the steam locomotive had to be tilted into a horizontal position to allow it to pass.[1]

Operation

In December 1910, the incline was already one mile (1.6 km) long and supposedly the steepest railway line in the world at that time. On this part of the route, a rope had to be hung from the winch on the back of the wagon, before it went down the steep section, to reduce its downward speed.[3][3]

When the sawmill was built in the Karekare Bush, the machines had also to be transported by the incline, which proved to be extremely difficult. All parts of the plant had to be transported with the forest tramway, which had a gradient of 1:1 (45°) in several places. Transporting a 10-tonne boiler along the line was no easy task, and it testifies to the persistence and ingenuity of the New Zealand bushman that in December 1910, apart from a minor derailment, the boiler could be brought to the site without a major breakdown, a task that took several days.[3]

In 1915 the forest enterprise and the forest railway were nationalized. The railway was then purchased by NZ Government Railways, which needed wood for its own purposes. The timber shipment ended when only a few kauri trees remained and the hills were affected by the effects of logging. The forest railway was abandoned in 1921 and its remains left to decay.[1]

Locomotives

_at_Piha_Tramway.png)

A small Bagnall steam locomotive called Sandfly was used on the line from the lower end of the funicular near Karekare to the quay near Whatipu,[1] originally used by a flaxmill in the Makerua Swamp in the Manawatu.

Another steam locomotive was delivered in 1914 in individual parts and assembled at the jetty for use on the Piha Tramway. The A 62 locomotive was built by Dubs in 1873 (manufacturer No. 656/73) and put into service in Christchurch and Timaru in January 1875. It was shipped to Wellington in 1897 and six years later awarded to the New Zealand Railways Maintenance Branch for use in the Pencarrow quarry, Wellington, and purchased by the Maintenance Branch in 1906. It was used between Piha and Whatipu in 1914, and five years later it returned to the Newmarket workshops to carry out shunting work. It was lent to a sawmill near Rotorua in 1921 and finally taken out of operation in 1926. It was then exhibited in the workshops of Otahuhu.[4]

References

- Paul and Rebecca da Rezzo: The Piha Tramway — Piha, Karekare and Whatipu. 30 September 2016. Retrieved on 22 April 2018.

- Wallace Badham: The Iron-Bound Coast: Karekare in the Early Years. Oratia Media Ltd, 2009, p. 51-59.

- A big undertaking: hauling a boiler up the inclined tramway at Piha. Auckland Weekly News, 29. December 1910.

- Piha Tramway engine at Otahuhu workshops. Archived 2018-04-23 at the Wayback Machine West Auckland Research Centre, Waitākere Central Library, JTD-04C-00019-2.