Photochromism

Photochromism is the reversible transformation of a chemical species between two forms by the absorption of electromagnetic radiation (photoisomerization), where the two forms have different absorption spectra.[1][2] In plain language, this can be described as a reversible change of colour upon exposure to light.

Applications

Sunglasses

One of the most famous reversible photochromic applications is color changing lenses for sunglasses, as found in eyeglasses. The largest limitation in using photochromic technology is that the materials cannot be made stable enough to withstand thousands of hours of outdoor exposure so long-term outdoor applications are not appropriate at this time.

The switching speed of photochromic dyes is highly sensitive to the rigidity of the environment around the dye. As a result, they switch most rapidly in solution and slowest in the rigid environment like a polymer lens. In 2005 it was reported that attaching flexible polymers with low glass transition temperature (for example siloxanes or poly(butyl acrylate)) to the dyes allows them to switch much more rapidly in a rigid lens.[3][4] Some spirooxazines with siloxane polymers attached switch at near solution-like speeds even though they are in a rigid lens matrix.

Supramolecular chemistry

Photochromic units have been employed extensively in supramolecular chemistry. Their ability to give a light-controlled reversible shape change means that they can be used to make or break molecular recognition motifs, or to cause a consequent shape change in their surroundings. Thus, photochromic units have been demonstrated as components of molecular switches. The coupling of photochromic units to enzymes or enzyme cofactors even provides the ability to reversibly turn enzymes "on" and "off", by altering their shape or orientation in such a way that their functions are either "working" or "broken".

Data storage

The possibility of using photochromic compounds for data storage was first suggested in 1956 by Yehuda Hirshberg.[5] Since that time, there have been many investigations by various academic and commercial groups, particularly in the area of 3D optical data storage which promises discs that can hold a terabyte of data. Initially, issues with thermal back-reactions and destructive reading dogged these studies, but more recently more-stable systems have been developed.

Novelty items

Reversible photochromics are also found in applications such as toys, cosmetics, clothing and industrial applications. If necessary, they can be made to change between desired colors by combination with a permanent pigment.

Solar energy storage

Researchers at the Center for Exploitation of Solar Energy at the University of Copenhagen Department of Chemistry are studying, the Photochromic Dihydroazulene–Vinylheptafulvene System, for possible application to harvest solar energy and store it for significant amounts of time.[6] Although storage lifetimes are attractive, for a real device it must of course be possible to trigger the back-reaction, which calls for further iterations in the future.[7]

History

Photochromism was discovered in the late 1880s, including work by Markwald, who studied the reversible change of color of 2,3,4,4-tetrachloronaphthalen-1(4H)-one in the solid state. He labeled this phenomenon "phototropy", and this name was used until the 1950s when Yehuda Hirshberg, of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel proposed the term "photochromism".[8] Photochromism can take place in both organic and inorganic compounds, and also has its place in biological systems (for example retinal in the vision process).

Overview

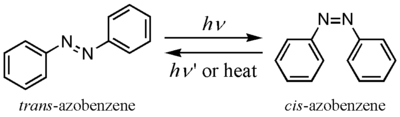

Photochromism does not have a rigorous definition, but is usually used to describe compounds that undergo a reversible photochemical reaction where an absorption band in the visible part of the electromagnetic spectrum changes dramatically in strength or wavelength. In many cases, an absorbance band is present in only one form. The degree of change required for a photochemical reaction to be dubbed "photochromic" is that which appears dramatic by eye, but in essence there is no dividing line between photochromic reactions and other photochemistry. Therefore, while the trans-cis isomerization of azobenzene is considered a photochromic reaction, the analogous reaction of stilbene is not. Since photochromism is just a special case of a photochemical reaction, almost any photochemical reaction type may be used to produce photochromism with appropriate molecular design. Some of the most common processes involved in photochromism are pericyclic reactions, cis-trans isomerizations, intramolecular hydrogen transfer, intramolecular group transfers, dissociation processes and electron transfers (oxidation-reduction).

Another requirement of photochromism is two states of the molecule should be thermally stable under ambient conditions for a reasonable time. All the same, nitrospiropyran (which back-isomerizes in the dark over ~10 minutes at room temperature) is considered photochromic. All photochromic molecules back-isomerize to their more stable form at some rate, and this back-isomerization is accelerated by heating. There is therefore a close relationship between photochromic and thermochromic compounds. The timescale of thermal back-isomerization is important for applications, and may be molecularly engineered. Photochromic compounds considered to be "thermally stable" include some diarylethenes, which do not back isomerize even after heating at 80 C for 3 months.

Since photochromic chromophores are dyes, and operate according to well-known reactions, their molecular engineering to fine-tune their properties can be achieved relatively easily using known design models, quantum mechanics calculations, and experimentation. In particular, the tuning of absorbance bands to particular parts of the spectrum and the engineering of thermal stability have received much attention.

Sometimes, and particularly in the dye industry, the term "irreversible photochromic" is used to describe materials that undergo a permanent color change upon exposure to ultraviolet or visible light radiation. Because by definition photochromics are reversible, there is technically no such thing as an "irreversible photochromic"—this is loose usage, and these compounds are better referred to as "photochangable" or "photoreactive" dyes.

Apart from the qualities already mentioned, several other properties of photochromics are important for their use. These include quantum yield, fatigue resistance, photostationary state, and polarity and solubility. The quantum yield of the photochemical reaction determines the efficiency of the photochromic change with respect to the amount of light absorbed. The quantum yield of isomerization can be strongly dependent on conditions. In photochromic materials, fatigue refers to the loss of reversibility by processes such as photodegradation, photobleaching, photooxidation, and other side reactions. All photochromics suffer fatigue to some extent, and its rate is strongly dependent on the activating light and the conditions of the sample. Photochromic materials have two states, and their interconversion can be controlled using different wavelengths of light. Excitation with any given wavelength of light will result in a mixture of the two states at a particular ratio, called the photostationary state. In a perfect system, there would exist wavelengths that can be used to provide 1:0 and 0:1 ratios of the isomers, but in real systems this is not possible, since the active absorbance bands always overlap to some extent. In order to incorporate photochromics in working systems, they suffer the same issues as other dyes. They are often charged in one or more state, leading to very high polarity and possible large changes in polarity. They also often contain large conjugated systems that limit their solubility.

Photochromic complexes

A photochromic complex is a kind of chemical compound that has photoresponsive parts on its ligand. These complexes have a specific structure: photoswitchable organic compounds are attached to metal complexes. For the photocontrollable parts, thermally and photochemically stable chromophores (azobenzene, diarylethene, spiropyran, etc.) are usually used. And for the metal complexes, a wide variety of compounds that have various functions (redox response, luminescence, magnetism, etc.) are applied.

The photochromic parts and metal parts are so close that they can affect each other's molecular orbitals. The physical properties of these compounds shown by parts of them (i.e., chromophores or metals) thus can be controlled by switching their other sites by external stimuli. For example, photoisomerization behaviors of some complexes can be switched by oxidation and reduction of their metal parts. Some other compounds can be changed in their luminescence behavior, magnetic interaction of metal sites, or stability of metal-to-ligand coordination by photoisomerization of their photochromic parts.

Classes of photochromic materials

Photochromic molecules can belong to various classes: triarylmethanes, stilbenes, azastilbenes, nitrones, fulgides, spiropyrans, naphthopyrans, spiro-oxazines, quinones and others.

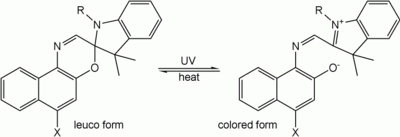

Spiropyrans and spirooxazines

One of the oldest, and perhaps the most studied, families of photochromes are the spiropyrans. Very closely related to these are the spirooxazines. For example, the spiro form of an oxazine is a colorless leuco dye; the conjugated system of the oxazine and another aromatic part of the molecule is separated by a sp³-hybridized "spiro" carbon. After irradiation with UV light, the bond between the spiro-carbon and the oxazine breaks, the ring opens, the spiro carbon achieves sp² hybridization and becomes planar, the aromatic group rotates, aligns its π-orbitals with the rest of the molecule, and a conjugated system forms with ability to absorb photons of visible light, and therefore appear colorful. When the UV source is removed, the molecules gradually relax to their ground state, the carbon-oxygen bond reforms, the spiro-carbon becomes sp³ hybridized again, and the molecule returns to its colorless state.

This class of photochromes in particular are thermodynamically unstable in one form and revert to the stable form in the dark unless cooled to low temperatures. Their lifetime can also be affected by exposure to UV light. Like most organic dyes they are susceptible to degradation by oxygen and free radicals. Incorporation of the dyes into a polymer matrix, adding a stabilizer, or providing a barrier to oxygen and chemicals by other means prolongs their lifetime.[9][10][11]

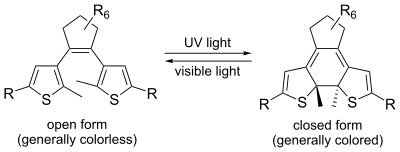

Diarylethenes

The "diarylethenes" were first introduced by Irie and have since gained widespread interest, largely on account of their high thermodynamic stability. They operate by means of a 6-pi electrocyclic reaction, the thermal analog of which is impossible due to steric hindrance. Pure photochromic dyes usually have the appearance of a crystalline powder, and in order to achieve the color change, they usually have to be dissolved in a solvent or dispersed in a suitable matrix. However, some diarylethenes have so little shape change upon isomerization that they can be converted while remaining in crystalline form.

Azobenzenes

The photochromic trans-cis isomerization of azobenzenes has been used extensively in molecular switches, often taking advantage of its shape change upon isomerization to produce a supramolecular result. In particular, azobenzenes incorporated into crown ethers give switchable receptors and azobenzenes in monolayers can provide light-controlled changes in surface properties.

Photochromic quinones

Some quinones, and phenoxynaphthacene quinone in particular, have photochromicity resulting from the ability of the phenyl group to migrate from one oxygen atom to another. Quinones with good thermal stability have been prepared, and they also have the additional feature of redox activity, leading to the construction of many-state molecular switches that operate by a mixture of photonic and electronic stimuli.

Inorganic photochromics

Many inorganic substances also exhibit photochromic properties, often with much better resistance to fatigue than organic photochromics. In particular, silver chloride is extensively used in the manufacture of photochromic lenses. Other silver and zinc halides are also photochromic. Yttrium oxyhydride is another inorganic material with photochromic properties[12].

Photochromic coordination compounds

Photochromic coordination complexes are relatively rare in comparison to the organic compounds listed above. There are two major classes of photochromic coordination compounds. Those based on sodium nitroprusside and the ruthenium sulfoxide compounds. The ruthenium sulfoxide complexes were created and developed by Rack and coworkers.[13][14] The mode of action is an excited state isomerization of a sulfoxide ligand on a ruthenium polypyridine fragment from S to O or O to S. The difference in bonding from between Ru and S or O leads to the dramatic color change and change in Ru(III/II) reduction potential. The ground state is always S-bonded and the metastable state is always O-bonded.Typically, absorption maxima changes of nearly 100 nm are observed. The metastable states (O-bonded isomers) of this class often revert thermally to their respective ground states (S-bonded isomers), although a number of examples exhibit two-color reversible photochromism. Ultrafast spectroscopy of these compounds has revealed exceptionally fast isomerization lifetimes ranging from 1.5 nanoseconds to 48 picoseconds.

See also

References

- Irie, M. (2000). "Photochromism: Memories and Switches – Introduction". Chemical Reviews. 100 (5): 1683–1684. doi:10.1021/cr980068l. PMID 11777415.

- Heinz Durr and Henri Bouas-Laurent Photochromism: Molecules and Systems, ISBN 978-0-444-51322-9

- Evans, Richard A.; Hanley, Tracey L.; Skidmore, Melissa A.; Davis, Thomas P.; et al. (2005). "The generic enhancement of photochromic dye switching speeds in a rigid polymer matrix". Nature Materials. 4 (3): 249–53. Bibcode:2005NatMa...4..249E. doi:10.1038/nmat1326. PMID 15696171.

- Such, Georgina K.; Evans, Richard A.; Davis, Thomas P. (2006). "Rapid Photochromic Switching in a Rigid Polymer Matrix Using Living Radical Polymerization". Macromolecules. 39 (4): 1391. Bibcode:2006MaMol..39.1391S. doi:10.1021/ma052002f.

- Hirshberg, Yehuda (1956). "Reversible Formation and Eradication of Colors by Irradiation at Low Temperatures. A Photochemical Memory Model". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 78 (10): 2304. doi:10.1021/ja01591a075.

- "Chemistry student makes sun harvest breakthrough".

- Cacciarini, M.; Skov, A. B.; Jevric, M.; Hansen, A. S.; Elm, J.; Kjaergaard, H. G.; Mikkelsen, K. V.; Brøndsted Nielsen, M. (2015). "Towards Solar Energy Storage in the Photochromic Dihydroazulene-Vinylheptafulvene System". Chemistry: A European Journal. 21 (20): 7454–61. doi:10.1002/chem.201500100. PMID 25847100.

- Prof. Mordechai Folman 1923 - 2004 Archived 2007-09-26 at the Wayback Machine

- G. Baillet, G. Giusti et R. GuglielmettiComparative photodegradation study between spiro[indoline-oxazine] and spiro[indoline-pyran] derivatives in solution, J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem., 70 (1993) 157-161

- G. Baillet, Photodegradation of Organic Photochromes in Polymers, Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst., 298 (1997) 75-82

- G. Baillet, G. Giusti and R. Guglielmetti, Study of the fatigue process and the yellowing of polymeric films containing spirooxazine photochromic compounds, Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn., 68 (1995) 1220-1225

- Mongstad, Trygve; Platzer-Bjorkman, Charlotte; Maehlen, Jan Petter; Mooij, Lennard P A; Pivak, Yevheniy; Dam, Bernard; Marstein, Erik S; Hauback, Bjorn C; Karazhanov, Smagul Zh. "A new thin film photochromic material: Oxygen-containing yttrium hydride". Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells. 95 (12): 3596-3599. doi:10.1016/j.solmat.2011.08.01.

- Rack, J. J. (2009). "Electron transfer triggeredsulfoxide isomerization in ruthenium and osmium complexes". Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 253 (1–2): 78–85. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2007.12.021.

- McClure, B. A.; Rack, J. J. (2010). "Isomerization inPhotochromic Ruthenium Sulfoxide Complexes". European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry. 2010 (25): 3895–3904. doi:10.1002/ejic.200900548.