Photochrom

Photochrom (Fotochrom, Photochrome[Note 1][2] or the Aäc process) is a process for producing colorized images from black-and-white photographic negatives via the direct photographic transfer of a negative onto lithographic printing plates. The process is a photographic variant of chromolithography (color lithography).

History

The process was invented in the 1880s by Hans Jakob Schmid (1856–1924), an employee of the Swiss company Orell Gessner Füssli—a printing firm whose history began in the 16th century.[3] Füssli founded the stock company Photochrom Zürich (later Photoglob Zürich AG) as the business vehicle for the commercial exploitation of the process and both Füssli[3] and Photoglob[4] continue to exist today. From the mid-1890s the process was licensed by other companies, including the Detroit Photographic Company in the US (making it the basis of their "phostint" process),[5] and the Photochrom Company of London.

Amongst the first commercial photographers to employ the technique were French photographer Félix Bonfils, British photographer Francis Frith and American photographer William Henry Jackson, all active in the 1880s. [6] The photochrom process was most popular in the 1890s, when true color photography was first developed but was still commercially impractical.

In 1898 the US Congress passed the Private Mailing Card Act which let private publishers produce postcards. These could be mailed for one cent each, while the letter rate was two cents. Publishers created thousands of photochrom prints, usually of cities or landscapes, and sold them as postcards. In this format, photochrom reproductions became popular.[7] The Detroit Photographic Company reportedly produced as many as seven million photochrom prints in some years, and ten to thirty thousand different views were offered.

After World War I, which ended the craze for collecting photochrom postcards, the chief use of the process was for posters and art reproductions. The last photochrom printer operated up to 1970.

Process

A tablet of lithographic limestone called a "litho stone" was coated with a light-sensitive surface composed of a thin layer of purified bitumen dissolved in benzene. A reversed halftone negative was then pressed against the coating and exposed to daylight (ten to thirty minutes in summer, up to several hours in winter), causing the bitumen to harden in proportion to the amount of light passing through each portion of the negative. Then a solvent such as turpentine was applied to remove the unhardened bitumen and retouch the tonal scale, strengthening or softening tones as required. Thus the image became imprinted on the stone in bitumen. Each tint was applied using a separate stone that bore the appropriate retouched image. The finished print was produced using at least six, but more commonly ten to fifteen, tint stones.

Gallery

A photochrom of Mulberry Street in New York City c 1900, which shows the evocative coloration characteristic of the process.

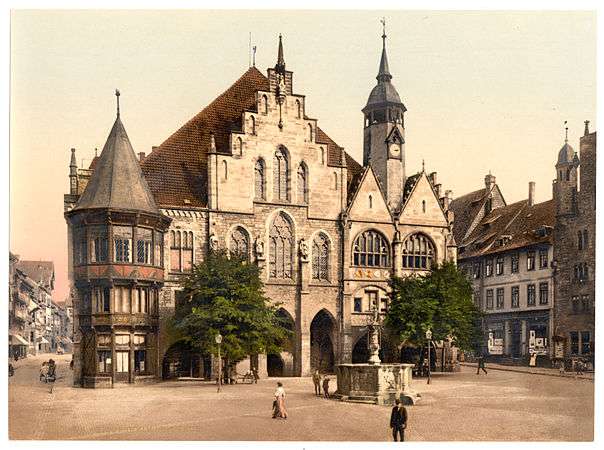

A photochrom of Mulberry Street in New York City c 1900, which shows the evocative coloration characteristic of the process. A photochrom of Hildesheim town hall in the 1890s, using fewer color plates

A photochrom of Hildesheim town hall in the 1890s, using fewer color plates Photochrom of the old Shakespeare Memorial Theatre, Stratford-on-Avon, England, c. 1890–1900

Photochrom of the old Shakespeare Memorial Theatre, Stratford-on-Avon, England, c. 1890–1900 A circa-1900 photochrom print of Shelbourne Hotel

A circa-1900 photochrom print of Shelbourne Hotel A photochrom of Belgian milk peddlers with a dogcart, c. 1890–1900

A photochrom of Belgian milk peddlers with a dogcart, c. 1890–1900 A photochrom of an elderly Irish woman using a spinning wheel, Co. Galway Ireland, c. 1890s

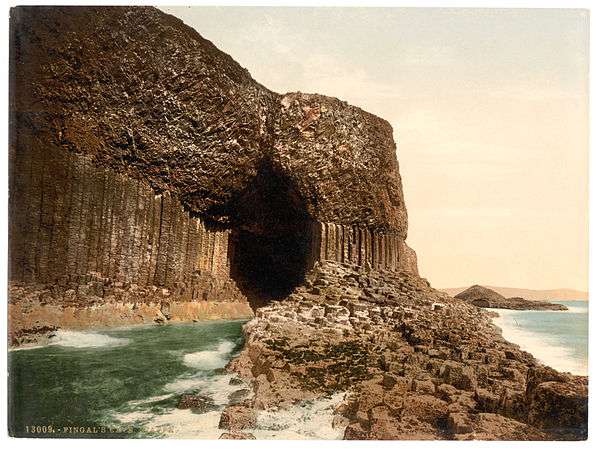

A photochrom of an elderly Irish woman using a spinning wheel, Co. Galway Ireland, c. 1890s Entrance to Fingal's Cave near low tide, 1900

Entrance to Fingal's Cave near low tide, 1900 HMY Osborne photochrom print, circa 1895

HMY Osborne photochrom print, circa 1895 Ruins of the Castle of Arques, near Dieppe, France, ca. 1895

Ruins of the Castle of Arques, near Dieppe, France, ca. 1895 Bergen, Norway, c. 1890s. Visible are Bergen Cathedral in the bottom left side, Holy Cross Church in the middle, the bay (Vågen) and the Bergenhus Fortress to the right of the opening of Vågen.

Bergen, Norway, c. 1890s. Visible are Bergen Cathedral in the bottom left side, Holy Cross Church in the middle, the bay (Vågen) and the Bergenhus Fortress to the right of the opening of Vågen..jpg) A circa 1897-1924 photochrome print of Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial, in Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia, U.S.A. (Detroit Photographic Company)

A circa 1897-1924 photochrome print of Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial, in Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia, U.S.A. (Detroit Photographic Company)

Notes

- "Photochrom" (English: /ˈfoʊtəˌkroʊm, -toʊ-/[1]) is the spelling used by the Library of Congress, for historical reasons, in its classification and description of its collection of such images. Variants of the spelling exist, both in English and in German. "Photochrome" is the English spelling used in some contexts, even by the Library of Congress in a few of its image descriptions. "Fotochrom" is the German spelling used today by Orell Füssli, the Swiss company that invented the process.

References

- "Photochrom". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2016-01-22.

- "Photochrome (1939–Present)". University of Vermont. Archived from the original on 2008-07-24.

- "Orell Füssli Company History (in German)". Ofv.ch. Retrieved 2012-06-16.

- "History / Erfolgsgeschichte" (in German). Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- "MetropoPostcard Guide to Printing Techniques 5". metropostcard.com.

- Farbige Reise, Paris bibliothèques, 2009, p. 41

- Marc Walter & Sabine Arque, “The World in 1900”, Thames & Hudson, 2007 contains about 300 well-reproduced photochromes from around the world.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Photochrom pictures. |

- Description of the Photochrom process

- The Library of Congress Public Domain Photochrom Prints Search

- Search at the Zurich Central Library (holds probably world's largest collection: 7600 of their 10000 prints are accessible online)

- Detroit Photographic Company’s Views of North America, ca. 1897–1924 from the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library