Paramythia

Paramythia (Greek: Παραμυθιά) is a town and a former municipality in Thesprotia, Epirus, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Souli, of which it is the seat and a municipal unit.[2] The municipal unit has an area of 342.197 km2.[3] The town's population is 2,730 as of the 2011 census.

Paramythia Παραμυθιά | |

|---|---|

Central street of Paramythia | |

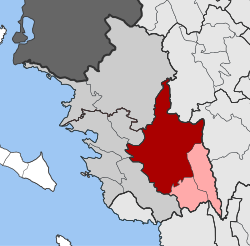

Paramythia Location within the regional unit  | |

| Coordinates: 39°28′N 20°30′E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Administrative region | Epirus |

| Regional unit | Thesprotia |

| Municipality | Souli |

| • Municipal unit | 342.2 km2 (132.1 sq mi) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Municipal unit | 7,459 |

| • Municipal unit density | 22/km2 (56/sq mi) |

| Community | |

| • Population | 2,730 (2011) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 462 00 |

| Area code(s) | 26660 |

| Vehicle registration | ΗΝΑ - ΗΝΒ - ΙΕ |

| Website | www.dimos-souliou.gr |

Paramythia acts as a regional hub for several small villages in the Valley of Paramythia, and features shops, schools, a gym, a stadium and a medical center. Primary aspects of the economy are agriculture and trade. The town is built on the slopes of Mount Gorilla and overlooks the valley, below. The Castle of Paramythia was built on a hill in one of the highest points of the town during the Byzantine period and today is open to the tourists.

The modern Egnatia Highway which links Igoumenitsa with Ioannina, goes through the valley, north of the town of Paramythia.

Name

The name "Paramythia" derives from one of the Virgin Mary's names in Greek ("Paramythia" in Greeks means comforter).[4] During the Byzantine era the town was also known as Agios Donatos (Greek: Άγιος Δονάτος), after Saint Donatus of Evorea,[5][6] the town's patron saint. This is also the basis of the Albanian[7] and the Turkish[8] name of Paramythia, Ajdhonat, Ajdonat, Ajdonati and Aydonat.

Geography

The Paramythia municipal unit consists of 23 communities. The total population of the municipal unit is 7,459 (2011). The town of Paramythia itself has a population of 2,730 and lies in an amphitheatre at an altitude of 750 m, at the foot of Mount Gorilla, between the Acheron and the Kalamas rivers. The Gorilla range (altitude 1,658 m) lies on the eastern side of the city and the Chionistra (1,644 m) to the Northeast. At the city limits is the Kokytos (Cocytus) River, one of the rivers of the underworld in Greek mythology. Paramythia's valley is one of the largest in Thesprotia and is one of the major agricultural areas in Epirus.

History

Antiquity

The earliest known inhabitants of the area were the Greek tribe of the Chaonians. Late bronze antiquities have been found in the "Tsardakia" area were a Mycenean settlement probably existed.[9][10]

Paramythia originated with the ancient Chaonian city of Photike (Ancient Greek: Φωτική), named after Photios, a leader of the Chaonians.[11] A famous hoard of bronzes dating from the mid 2nd Century AD, nineteen bronze sculptures were discovered during the 1790s, near the village of Paramythia. Soon after their discovery, the hoard was dispatched to St Petersburg, to become part of Catherine the Great's collection. After her death, the original hoard was dispersed to various European collections. Eventually fourteen of the statuettes reached the British Museum.[12]

Medieval era

Photike, as with the rest of Epirus, became part of the Roman and subsequently Byzantine Empires. In the late Roman era it was the seat of a Bishopric and was renamed after Saint Donatus of Evorea.

Following the fall of Constantinople to the Fourth Crusade in 1204, Photike became part of the Despotate of Epirus. The Despotate remained independent for the next two centuries, maintaining the Greek Byzantine traditions. In 1359 the Greek notables of the region together with those of nearby Ioannina sent a delegation to the Serb ruler Symeon to support their independence against possible attacks by Albanian tribesmen. The town remained part of the Despotate of Epirus but during the reign of despot Thomas II Preljubović the Greek commanders of Photike/Agios Donatos refused to accept them as their ruler. The town fell to the Ottomans in 1449.[13] Paramythia was part of the Ottoman Sanjak of Ioannina.[14][15]

Modern era

A Greek language school, had been attested since 1682. It declined and close in the mid-18th century,[16] however, another Greek school was continuously operating from the late 17th century and at 1842 was expanded with additional classes.[17] In 1854 a major revolt took place in Epirus and the town came briefly under the control of guerilla Souliote forces that demanded the union of Epirus with Greece.[18]

Population movements to the town that occurred from the middle of the 19th century weakened the Muslim elite and led to the gradual Hellenization of former Albanian-majority towns in the area such as Paramythia in the 1920s.[19] After the end of the Balkan Wars (1912–1913) the town became part of the Greek state, as with the rest of Epirus region. During the interwar period, Paramythia was a centre of the Albanian speaking area of Chameria and mainly an Albanian speaking market town that after 1939 increasingly became Greek speaking.[20] During the Greek-Italian War the town was burned by Cham Albanian bands (October 28-November 14, 1940)[21] In the following Axis occupation of Greece (1941-1944) the town had a population of 6,000 inhabitants; 3,000 Greeks and 3,000 Cham Albanians.[22] Almost all buildings inhabited by Muslim Albanians in the town were destroyed during World War II warfare.[23]

On the night of 27 September 1943, Cham militias arrested 53 Greek citizens in Paramythia and executed 49 of them two days later. This action was orchestrated by the brothers Nuri and Mazar Dino (an officer of the Cham militia) in order to get rid of the town's Greek representatives and intellectuals. According to German reports, Cham militias were also part of the firing squad.[24]

During September 20–29, as a result of serial terrorist activities, at least Greek 75 citizens were killed in Paramythia and 19 municipalities were destroyed.[25] On September 30, the Swiss representative of the International Red Cross, Hans-Jakob Bickel, visited the area and confirmed the atrocities committed by the Cham militia in collaboration with the Axis forces.[26]

Notable inhabitants

- Sotirios Voulgaris, the notable Greek [27] who founded the jewelry and luxury goods company Bulgari. His jewelry store in Paramythia survives. Following his wish, his sons funded the building of the elementary school of the town.

- Dionysius the Philosopher (1560–1611), Greek monk and revolutionary.

- Alexios Pallis (1803–1885), Greek writer.

Subdivisions

The municipal unit Paramythia is subdivided into the following communities (constituent villages in brackets):

- Agia Kyriaki

- Ampelia (Ampelia, Agios Panteleimonas, Rapi)

- Chrysavgi

- Elataria

- Grika

- Kallithea (Kallithea, Avaritsa, Vrysopoula)

- Karioti

- Karvounari (Karvounari, Kyra Panagia)

- Krystallopigi (Krystallopigi, Kefalovryso)

- Neochori (Neochori, Agios Georgios, Neraida)

- Pagkrates

- Paramythia (Paramythia, Agios Georgios, Agios Donatos)

- Pente Ekklisies

- Petousi

- Petrovitsa

- Plakoti

- Polydroso

- Prodromi (Prodromi, Dafnoula)

- Psaka (Psaka, Nounesati)

- Saloniki

- Sevasto

- Xirolofos (Xirolofos, Rachouli)

- Zervochori (Zervochori, Asfaka, Kamini)

See also

- List of cities in ancient Epirus

- Axis-Cham Albanian collaboration

- Paramythia executions

- Paramythia Hoard

- Metropolis of Paramythia, Filiates, Giromeri and Parga

Gallery

Old part of Paramythia

Old part of Paramythia The Byzantine castle seen from the streets of Paramythia

The Byzantine castle seen from the streets of Paramythia Byzantine church of the Koimesis (13th century AD)

Byzantine church of the Koimesis (13th century AD).jpg) Byzantine baths of Paramythia (early 15th century AD)

Byzantine baths of Paramythia (early 15th century AD) Interior of the Byzantine baths

Interior of the Byzantine baths Ottoman tower (Koulia, 17th century AD)

Ottoman tower (Koulia, 17th century AD) Rigas mansion (1872)

Rigas mansion (1872) The marketplace of Paramythia (1915)

The marketplace of Paramythia (1915)

References

- "Απογραφή Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2011. ΜΟΝΙΜΟΣ Πληθυσμός" (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority.

- Kallikratis law Greece Ministry of Interior (in Greek)

- "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece.

- paramythia.gr Archived 2002-06-09 at Archive.today

- Elsie, Robert (2000). "The Christian Saints of Albania". Balkanistica. American Association for South Slavic Studies. 13: 36.

- Epirus, 4000 years of Greek history and civilization M. V. Sakellariou. Ekdotike Athenon, 1997. ISBN 978-960-213-371-2, p. 183 "modern Paramythia bore the Saint's name for many centuries..." (c. from 7th to 15th centuries)

- Duka, Ferit; Society and Economy in Ottoman Çameria: Kazas of Ajdonat and Mazrak (Second Half of the 16th Century) p.3, periodic Historical Studies (Studime historike) issue: 34 / 2004

- Evliya Çelebi Seyahatnamesi, Hazırlayanlar: Seyit Ali Kahraman, Yücel Dağlı, YKY Yayınları, Istanbul 2002, pp. 107. (in Turkish)

- Papadopoulos Thanasis J. The Late Bronze Age Daggers of the Aegean I: The Greek Mainland, Franz Steiner Verlag, 1998, pp. 22, 23

- L'habitat égéen préhistorique: actes de la Table Ronde internationale organisé par le Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, France, 1987, p. 361

- An Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis: An Investigation Conducted by The Copenhagen Polis Centre for the Danish National Research Foundation by Mogens Herman Hansen, 2005, page 340.

- British Museum Collection

- Epirus, as an Independent State: The Despotate of Epirus (in "4000 years of Greek history and civilization" Nicol D. Ekdotike Athenon, 1997. ISBN 978-960-213-371-2, p. 214, 219.

- H. Karpat, Kemal (1985). Ottoman population, 1830-1914: demographic and social characteristics. p. 146. ISBN 9780299091606. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- Motika, Raoul (1995). Türkische Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichte (1071-1920). p. 297. ISBN 9783447036832. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

Sancaks Yanya (Kazas: Yanya, Aydonat (Paramythia), Filat (Philiates), Meçova (Metsovo), Leskovik (war kurzzeitig Sancak) und Koniçe (Konitsa)

- "Σχολή Παραμυθίας. [School of Paramythia]". Κάτοπρον Ελληνικής Επιστήμης και Φιλοσοφίας (University of Athens) (in Greek). Retrieved 2010-10-30.

- Sakellariou, M. V. (1997). Epirus, 4000 years of Greek history and civilization. Ekdotike Athenon. p. 306. ISBN 978-960-213-371-2.

- M. V. Sakellariou. Epirus, 4000 years of Greek history and civilization. Ekdotike Athenon, 1997. ISBN 978-960-213-371-2, p. 288

- Tsoutsoumpis, Spiros (2015). "Violence, resistance and collaboration in a Greek borderland: the case of the Muslim Chams of Epirus «Qualestoria» n. 2, dicembre 2015". Qualestoria. 2: 24–25. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

Until the early 20th century, economic strength lay in the hands of the Muslim landowner class, many of whom were engaged in commerce and usury. This situation had been changing gradually since the mid-19th century as small numbers of individuals and later families from the province of Ioannina, settled in the principal towns of the region establishing business. By the 1920s, they were joined by local men who slowly came to constitute an elite that threatened to wrest economic control from the Muslim notables. The presence of these men led to a gradual Hellenization of formerely Albanian-majority towns, like Margariti and Filiates that was viewed with disdain by the Muslim peasantry

- Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1967). Epirus: the Geography, the Ancient Remains, the History and Topography of Epirus and Adjacent Areas. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 27. ISBN 9780198142539.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) "The market towns of Filiates and Paramythia were mainly Albanian in speech before 1939, but Greek speech was beginning to flow back to them."; p. 50. "and it is the most southerly of the villages of Tsamouria, the Albanian speaking area of which Margariti and Paramythia are centres."

- Georgia Kretsi. Verfolgung und Gedächtnis in Albanien: eine Analyse postsozialistischer Erinnerungsstrategien. Harrassowitz, 2007. ISBN 978-3-447-05544-4, p. 283.

- Meyer 2008: 464

- Kiel, Machiel (1990). Ottoman architecture in Albania, 1385-1912. Research Centre for Islamic History, Art and Culture. p. 3. ISBN 978-92-9063-330-3. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- Meyer 2008: 469-471

- Meyer 2008: 476

- Meyer 2008: 498

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-08-15. Retrieved 2009-06-03.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Sources

- Meyer, Hermann Frank (2008). Blutiges Edelweiß: Die 1. Gebirgs-division im zweiten Weltkrieg [Bloodstained Edelweiss. The 1st Mountain-Division in WWII] (in German). Ch. Links Verlag. ISBN 978-3-86153-447-1.