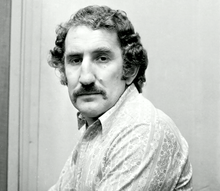

Philip Jacobson

Philip Samuel Jacobson (10 September 1938 – 1 January 2018) was a British journalist and war correspondent known for his reporting for The Sunday Times Insight team of the events of Bloody Sunday in Northern Ireland in 1972.

Early life and family

Philip Jacobson was born on 10 September 1938 to Sydney, later Baron, Jacobson, and his wife. His father was political editor of the Daily Mirror and later editor of the Daily Herald and The Sun. Jacobson was brought up in Stanmore, Middlesex, and educated in Dorset and at schools elsewhere. He did his national service in a tank regiment that was stationed in Malaya during the emergency. Afterwards he took a degree in politics at the London School of Economics.[1]

He married Ann Mathison in 1967 and they had two sons, both of whom work in journalism.[1]

Career

Jacobson started his journalistic career as a heating specialist on Ideal Home magazine. He was later financial correspondent for The Times in New York. In 1970 he joined The Sunday Times where he reported on foreign wars in Bangladesh, Cyprus, Lebanon, Vietnam, El Salvador and Chad among others. He was briefly imprisoned in Calcutta. He covered the Yom Kippur War in 1973 in which his successor was killed. From 1987 to 1992 he was the Paris correspondent for The Times.[1] He was best known for his reporting with Peter Pringle for The Sunday Times Insight team of the events of Bloody Sunday in Northern Ireland in 1972, which the pair turned into a book in 2000 titled Those are real bullets, aren't they?[1][2]

In 1977, he and other members of The Sunday Times Insight team produced a book on Aristotle Onassis (died 1975). It was criticised by Taki Theodoracopulos in The Spectator for opportunism, an ironic lack of insight and being largely derivative of existing sources.[3] In 2009, Jacobson won the feature writer of the year award for his reporting on the legal costs of the Bloody Sunday Inquiry into that day.[1][4] He freelanced during his later career, writing for the Daily Telegraph, Mail on Sunday, Daily Mail and Mail Online.[5]

Among the journalistic legends that attach to him is one of an eight-hour lunch with his colleague Peter Pringle in Bogotá, Colombia, in which 13 bottles of alcohol were drunk, leading to applause from the staff when the diners left the restaurant,[1][6] and his lack of success in horse race betting which he sometimes conducted using a mobile phone while reporting from the battlefield.[1]

Death

Jacobson died at the age of 79 on 1 January 2018 after contracting meningitis.[1] His funeral was at Mortlake Crematorium.[7]

Selected publications

- Aristotle Onassis. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 1977. (With Nicholas Fraser, Mark Ottaway, and Lewis Chester) ISBN 978-0-297-77426-6

- Those are real bullets, aren't they? Bloody Sunday, Derry, 30 January 1972. Fourth Estate, London, 2000. (With Peter Pringle) ISBN 1-84115-316-8

References

- Philip Jacobson. The Times, 16 January 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2018. (subscription required)

- Those Are Real Bullets, Aren’t They? Archived 2018-02-15 at the Wayback Machine Harper Collins. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Social climber meets hustler. Archived 2018-01-25 at the Wayback Machine Taki Theodoracopulos, The Spectator, 19 November 1977, p. 20.

- Live blog: British Press Awards 2009. Archived 2018-01-25 at the Wayback Machine Press Gazette, 31 March 2009. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Articles by Philip Jacobson. Archived 2018-01-25 at the Wayback Machine journalisted.com Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- "Lives Remembered: Philip Jacobson", Peter Pringle, The Times, 2 February 2018, p. 58.

- Philip Samuel Jacobson. Archived 2018-01-25 at the Wayback Machine legacy.com Retrieved 24 January 2018.