Peter Rindisbacher

Peter Rindisbacher (12 April 1806 – 12 August or 13 August 1834) was a Swiss artist who specialized in watercolors and illustrations dealing with First Nation tribes of mid-Western Canada and the United States, mostly depictions of the Anishinaabe, Cree, and Sioux, usually in group action or genre scenes.[1] He seldom did individual portraits; however, he painted himself into a few interior tipi scenes, usually smoking a pipe. He commonly referred to the tipis as tents, such as in the title, Inside a Skin Tent.[2]

Peter Rindisbacher | |

|---|---|

| Born | Peter Rindisbacher 12 April 1806 Emmental, Canton of Berne, Switzerland |

| Died | 13 August 1834 (aged 28) |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | One year in a Swiss art school as a youth, but mostly Self-taught |

| Known for | Watercolor painting |

| Movement | Naïve Realism |

Biography

Rindisbacher emigrated from Switzerland to western Canada with his family when he was fifteen. The family was recruited by an agent of Red River Colony, established by the Earl of Selkirk, to settle the area located near present-day Winnipeg, Manitoba. Lord Selkirk's land grant, called Assiniboia, was administered by a governor and council but, as all the colony's officials had connections with the Hudson's Bay Company, the colony was effectively an arm of Hudson's Bay's operations. The colony faced difficulties due to a disastrous flood of the Red River, on the eastern boundary of North Dakota north to Lake Winnipeg, which led to damaged crops and starvation.[3] The Rindisbacher family relocated to Wisconsin in 1826, and then settled permanently in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1829.[4]

Career

From the age of fifteen until his death, possibly of cholera, at age 28, Rindisbacher was a producing artist.[4] He began working with charcoal as a young boy, with the encouragement of his father, and received one year of formal training with artist Jakob Samuel Weibel in Switzerland.[3] He executed sketches and watercolors of his family's journey from Europe to western Canada, life and company officials in the Red River Colony, and Indians and animals in west-central Canada and the midwestern United States, including the Chippewa and Metis people living along the Red River Trails. At age twenty-three, upon moving to St. Louis, Rindisbacher established an artist's studio, where he also produced illustrations for magazines and book covers, and contributed to the History of the Indian Tribes of North America collection.

Paintings, selected

- The Buffalo Hunt - circa 1822-24.

- Inside of a Skin Tent - 1824, one of the earliest studies of a tipi by a non-Indian. Library and Archives Canada Collection.

- Indian hunters pursuing buffalo in the early spring - 1822, painted when the artist was age sixteen.

- A Halfcast and his Two Wives based on a sketch from about 1825.[5]

- Hunting the Buffalo - 1836, frontispiece for Volume 1 of the History of the Indian Tribes of North America by Thomas L. McKenney and James Hall, 1836.

- War dance of the Sauks and Foxes - 1834, frontispiece for Volume 2 of the History of the Indian Tribes of North America by Thomas L. McKenney and James Hall, 1838.

- Chippewa mode of traveling in spring and summer - 1825, West Point Museum Collection.

Gallery

Extremely wearisome journeys at the portages (1821)

Extremely wearisome journeys at the portages (1821) Cold night camp on the inhospitable shores of Lake Winnipeg (1821)

Cold night camp on the inhospitable shores of Lake Winnipeg (1821).png) Winter Fishing on the Ice (1821)

Winter Fishing on the Ice (1821) Summer View in the environs of the Company Fort Douglas on the Red River (1822)

Summer View in the environs of the Company Fort Douglas on the Red River (1822) Buffalo Hunting in the summer (1822)

Buffalo Hunting in the summer (1822) Colonists on the Red River in North America (1822)

Colonists on the Red River in North America (1822) Saulteaux standing in a winter landscape (1822)

Saulteaux standing in a winter landscape (1822) Pembina Forts in 1822

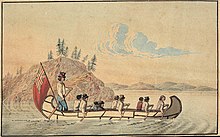

Pembina Forts in 1822 Hudson's Bay Company officials in an express canoe crossing a lake (1825)

Hudson's Bay Company officials in an express canoe crossing a lake (1825) The Red Lake Chief making a speech to the Governor of Red River at Fort Douglas (1825)

The Red Lake Chief making a speech to the Governor of Red River at Fort Douglas (1825) Assiniboine hunting buffalo on horseback (1830)

Assiniboine hunting buffalo on horseback (1830)

Legacy

Having spent fifteen years painting the native people of central North America, Rindisbacher died on 13 August 1834, several days after attending a militia meeting in St. Louis. At the time, George Catlin, who is often given credit for being the first professional painter to depict the American Indians of the Great Plains, was only four years through his six years of western expeditions in 1830-1836. As a professional painter, Rindisbacher preceded Catlin in the west by at least ten years, and is considered the first resident professional artist west of the Great Lakes.[4] Rindisbacher is known to have produced more than 124 paintings during his career. Forty of his artworks are currently held by the Library and Archives of Canada, Ottawa.[3] Other large concentrations of his paintings are located in the collections of the West Point Museum of the United States Military Academy and the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

References

- Josephy, Alvin M. Jr., The Artist was a Young Man: The Life Story of Peter Rindisbacher. Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum, 1970.

- Painted in 1824, one of the earliest studies of a tipi by a non-Indian. Library and Archives Canada Collection.

- "Peter Rindisbacher: Beauty by Commission". Library and Archives Canada. June 30, 2016. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- Rindisbacher's biography at the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online

- Van Kirk, Sylvia. Many Tender Ties. (Winnipeg: Watsn and Dwyer Publishing Ltd., 1980) p. 100

Bibliography

- Laura Peers, "'Almost True': Peter Rindisbacher's Early Images of Rupert's Land, 1821-26," Art History, 32,3 (2009), 516-544.