Peter Carew (died 1580)

Sir Peter Carew (died 25 August 1580) was an English soldier who was slain at the Battle of Glenmalure in Ireland. He was a member of a prominent Devonshire gentry family, and should be distinguished from his first cousin (and immediate predecessor as head of the family) Sir Peter Carew (c.1514–1575) of Mohuns Ottery, Luppitt, Devon.

Origins

Peter Carew was the eldest son of George Carew (1497/8–1583), Dean of Windsor, Dean of Exeter and Archdeacon of Totnes, third son of Sir Edmund Carew, Baron Carew, of Mohuns Ottery in the parish of Luppitt, Devon, by his wife Catharine Huddesfield, a daughter and co-heiress of Sir William Huddesfield (died 1499) of Shillingford St George in Devon, Attorney-General to Kings Edward IV (1461–1483)[1] and Henry VII (1485–1509).[2] His younger brother was George Carew (1555–1629), later 1st Earl of Totnes; and his sister was Mary Carew (d. 1604), the wife of Walter II Dowrich of Dowrich in the parish of Sandford near Crediton in Devon. Mary Carew's monumental brass survives in Sandford Church.

Career

Carew inherited the Irish territorial barony of Idrone or Odrone, representing about 6,360 acres, or a fifth part of County Carlow, from his senior cousin, Sir Peter Carew (c.1514–1575) of Mohuns Ottery.[3] In September 1579 he was knighted.[4]

On 25 August 1580, during the Second Desmond Rebellion, Carew was in the vanguard of the army of Arthur Grey, 14th Baron Grey de Wilton, when it was ambushed by Irish insurgents in the narrow valley of Glenmalure in the Wicklow uplands. The English attempted to climb the steep valley sides, but Carew, exhausted by trying to run in heavy armour, was captured. He was disarmed, and his captors planned to hold him for ransom, until "one villaine most butcherlie ... with his sword slaughtered and killed him".[5] Sir Peter's brother, George, who was also present at the engagement but not in the vanguard, wrote to Sir Francis Walsingham of his determination "to leave my bones by his, or else I will be thoroughly satisfied with revenge", and subsequently made it his business to kill two of those implicated in his brother's death.[6]

Family

Carew married Audrey Gardiner, a daughter of William Gardiner of Grove, Buckinghamshire. The couple had a son, Peter, who died young; and a daughter, Anne, who married first William Wilford, and second (in 1605) Sir Allen Apsley (1567–1630).[7] Audrey survived Sir Peter and married as her second husband Sir Edmund Verney[2] (1535–1599) of Pendley in the parish of Tring, Hertfordshire,[8] Sheriff of Buckinghamshire and Sheriff of Hertfordshire.[9]

Commemoration

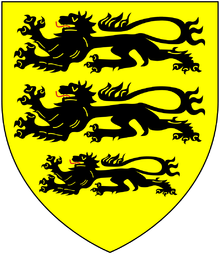

Carew is associated with an extravagant two-tiered tomb monument in the Chapel of St John the Evangelist in Exeter Cathedral, of which the primary commemorative subjects are his uncle, Sir Gawen Carew (c.1508–1584), and Sir Gawen's third wife, Elizabeth née Norwich (d. 1594), a Lady of the Bedchamber to Elizabeth I.[10][11] The monument was erected in 1589, and heavily restored in 1857. In addition to effigies of Sir Gawen and Elizabeth, it displays much strapwork decoration and heraldry, including 27 shields containing 52 distinct coats of arms marshalled in a total of 359 impalements and quarterings.[12] The whole forms "an elaborate shrine to Carew ancestry and kinship".[13]

A prominent Latin inscription formerly on the monument's pediment explicitly commemorated Sir Peter, but is now lost. It began "Hic scitus est praeter nobilis vir Petrus Carew eques Auratus ..." ("Here too lies the illustrious man Peter Carew, knight ..."), raising the possibility that his body, or some token part of it, was recovered from the battlefield at Glenmalure and returned to Exeter for burial.[14]

A third effigy, occupying a recess at the base of the monument, is dressed in armour and posed in a cross-legged attitude suggestive of the 14th century; and it has long been believed that this represents Sir Peter in the guise of a fallen warrior.[15] The identification is supported by another painted inscription, which survives in restored form running around three sides of the cornice, and which alludes to "... Sir Peter Carew Knyght, under figured ...".[16] However, the inscription is not original to the monument (it can date from no earlier than 1605), and it now appears considerably more likely that the cross-legged figure was intended to represent Adam Montgomery de Carew, the semi-legendary progenitor of the Carew family.[17]

References

- Vivian, J.L., ed. (1895). The Visitations of the County of Devon: comprising the Heralds' Visitations of 1531, 1564 & 1620. Exeter. p. 246.

- Vivian 1895, p.135.

- Hooker, John, The Life and Times of Sir Peter Carew: Kt., (from the Original Manuscript), p. 254, footnote

- Shaw, William A. (1906). The Knights of England. 2. London: Sherratt & Hughes. p. 80.

- Hooker, John (1587). "The Supplie of the Irish Chronicles extended to this present yeare of our Lord 1586, and the 28 of the reigne of queene Elisabeth". In Holinshed, Raphael (ed.). The First and Second Volumes of Chronicles (2nd ed.). London. p. 170.

- Brewer, J. S.; Bullen, William, eds. (1867). Calendar of the Carew Manuscripts preserved in the Archiepiscopal Library at Lambeth. 1. London: Longmans. pp. xiv, xvi–xviii.

- Harris, Oliver D. (2014). "The generations of Adam: the monument of Sir Gawen Carew in Exeter Cathedral". Church Monuments. 29: 40–71 (47, 56–7, 65).

- "VERNEY". tudorplace.com.ar. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- Burke, Bernard, "Genealogical History of the Dormant, Abeyant, Forfeited, and Extinct Peerages of the British Empire", London, 1866, p.554

- Harris, "Generations of Adam". An inscription added in 1857 suggests that the lady is Sir Gawen's second wife, Mary née Wotton (c.1500–1558), widow of Sir Henry Guildford (1489–1532), but this is an error.

- Harris, Oliver (2014). "A Lady of the Bedchamber to Elizabeth I: Elizabeth, Lady Carew". The Friends of Exeter Cathedral Annual Report. Exeter. 84: 28–31.

- Harris, "Generations of Adam", p. 40.

- Harris, "Generations of Adam", p. 63.

- Harris, "Generations of Adam", pp. 59, 65.

- Erskine, Audrey; Hope, Vyvyan; Lloyd, John (1988). Exeter Cathedral: A Short History and Description. Exeter: Exeter Cathedral. p. 106. ISBN 0-9503320-4-6.

- Harris, "Generations of Adam", pp. 57, 65.

- Harris, "Generations of Adam", pp. 57–62.