Persecution in Lyon

The persecution in Lyon in AD 177 was a persecution of Christians in Lugdunum, Roman Gaul (present-day Lyon, France), during the reign of Marcus Aurelius (161-180). An account of this persecution is a letter preserved in Eusebius's Ecclesiastical History, book 5, chapter 1. Gregory of Tours describes the persecution in De Gloria martyrum.

Background

Lugdunum was an important Roman city in Gaul. Founded on the Rhone river in 43 BC by Lucius Munatius Plancus, it served as the capital of the Roman province Gallia Lugdunensis. The emperor Claudius was born in Lugdunum. The first known Christian community established in Lugdunum some time in the 2nd century was led by a bishop named Pothinus from Asia Minor.

In the first two centuries of the Christian era, it was local Roman officials who were largely responsible for persecutions. In the second century, the Caesars were largely content to treat Christianity as a local problem, and leave it to their subordinates to deal with. Until the reign of emperor Decius (249-251) persecution was local and sporadic. For Roman governors being a Christian was in itself a subversive act, because it entailed a refusal to sacrifice to the gods of Rome, including the deified emperor. [1]

Account of the persecution

By 177, a number of the Christians in the area of Vienne and Lyons were Greeks from Asia.[2] Before the actual outbreak of violence, Christians were forbidden from the marketplace, the forum, the baths, or to appear in any public places.[3] If they did appear in public they were subject to being mocked, beaten, and robbed by the mob. The homes of Christians were vandalized. (Hist. Eccl., 5.1.5,7). The martyrs of Lyons were accused of "Thyestean banquets and Oedipean intercourse," a reference to cannabalism and incest.[1]

How long all of this lasted is not indicated, but eventually the authorities seized the Christians and questioned them in the forum in front of the populace. They were then imprisoned until the arrival of the governor.[3]

According to Eusebius (Hist. Eccl.,5.4), while yet a presbyter or elder, St. Irenaeus was sent with a letter, from certain members of the Church of Lyons awaiting martyrdom, to Eleutherus, bishop of Rome.

When the governor arrived at Lugdunum, he interrogated them in front of the populace again, mistreating them to such a degree that Vettius Epagathus, a Christian and man of high social standing, requested permission to testify on behalf of the accused. This request was refused and instead the governor arrested Vettius Epagathus when he confessed to being a Christian (5.1.9-10).

These Christians endured torture while the authorities continued to apprehend others. Two of their pagan servants were seized and, fearing torture, falsely charged the Christians with incest and cannibalism (Hist. Eccl., 5.1.12-13).

What followed was the torture of the captive Christians by various means. In the end, all were killed, some of whom had recanted but later returned to the faith (Hist. Eccl., 5.1.45-46).

Deaths

There were 48 victims at Lugdunum, half of them were of Greek origin, half Gallo-Roman.[4] The elderly Bishop Pothinus, first Bishop of Lugdunum, was beaten and scourged, and died shortly after in prison.

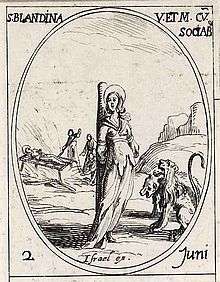

A slave, Blandina was subjected to extreme torture. She was initially exposed, hung on a stake, to be the food of the beasts let loose upon her. As none of the beasts at that time touched her; she was brought back again to the prison, before being cast in a net and thrown before a bull.[5]

Also martyred at this time were Attalus, Epipodius and Alexander, Maturus, Saint Ponticus, a fifteen-year-old boy, and Sanctus, a deacon from Vienne.[3]

References

- Walton, Stephen. "Why were the Early Christians Persecuted?", The Theologian

- Butler, Alban. "St. Pothinus, Bishop, Sanctus, Attalus, Blandina, &c., Martyrs of Lyons", Lives of the Saints, Vol.VI, 1866

- "The Letter of the Churchs of Vienna and Lyons to the Churches of Asia and Phrygia", Medieval Sourcebook, Fordham University

- Goyau, Georges. "Lyons." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 22 Apr. 2013

- Whitehead, Kenneth D. "Witnesses of the Passion", Touchstone Magazine