Permutation graph

In mathematics, a permutation graph is a graph whose vertices represent the elements of a permutation, and whose edges represent pairs of elements that are reversed by the permutation. Permutation graphs may also be defined geometrically, as the intersection graphs of line segments whose endpoints lie on two parallel lines. Different permutations may give rise to the same permutation graph; a given graph has a unique representation (up to permutation symmetry) if it is prime with respect to the modular decomposition.[1]

Definition and characterization

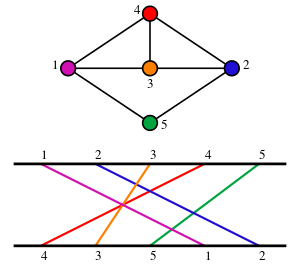

If σ = (σ1,σ2, ..., σn) is any permutation of the numbers from 1 to n, then one may define a permutation graph from σ in which there are n vertices v1, v2, ..., vn, and in which there is an edge vivj for any two indices i and j for which i < j and σi > σj. That is, two indices i and j determine an edge in the permutation graph exactly when they determine an inversion in the permutation.

Given a permutation σ, one may also determine a set of line segments si with endpoints (i,0) and (σi,1). The endpoints of these segments lie on the two parallel lines y = 0 and y = 1, and two segments have a non-empty intersection if and only if they correspond to an inversion in the permutation. Thus, the permutation graph of σ coincides with the intersection graph of the segments. For every two parallel lines, and every finite set of line segments with endpoints on both lines, the intersection graph of the segments is a permutation graph; in the case that the segment endpoints are all distinct, a permutation for which it is the permutation graph may be given by numbering the segments on one of the two lines in consecutive order, and reading off these numbers in the order that the segment endpoints appear on the other line.

Permutation graphs have several other equivalent characterizations:

- A graph G is a permutation graph if and only if G is a circle graph that admits an equator, i.e., an additional chord that intersects every other chord.[2]

- A graph G is a permutation graph if and only if both G and its complement are comparability graphs.[3]

- A graph G is a permutation graph if and only if it is the comparability graph of a partially ordered set that has order dimension at most two.[4]

- If a graph G is a permutation graph, so is its complement. A permutation that represents the complement of G may be obtained by reversing the permutation representing G.

Efficient algorithms

It is possible to test whether a given graph is a permutation graph, and if so construct a permutation representing it, in linear time.[5]

As a subclass of the perfect graphs, many problems that are NP-complete for arbitrary graphs may be solved efficiently for permutation graphs. For instance:

- the largest clique in a permutation graph corresponds to the longest decreasing subsequence in the permutation defining the graph, so the clique problem may be solved in polynomial time for permutation graphs by using a longest decreasing subsequence algorithm.[6]

- likewise, an increasing subsequence in a permutation corresponds to an independent set of the same size in the corresponding permutation graph.

- the treewidth and pathwidth of permutation graphs can be computed in polynomial time; these algorithms exploit the fact that the number of inclusion minimal vertex separators in a permutation graph is polynomial in the size of the graph.[7]

Relation to other graph classes

Permutation graphs are a special case of circle graphs, comparability graphs, the complements of comparability graphs, and trapezoid graphs.

The subclasses of the permutation graphs include the bipartite permutation graphs (characterized by Spinrad, Brandstädt & Stewart 1987) and the cographs.

Notes

References

- Baker, Kirby A.; Fishburn, Peter C.; Roberts, Fred S. (1971), "Partial orders of dimension 2", Networks, 2 (1): 11–28, doi:10.1002/net.3230020103.

- Bodlaender, Hans L.; Kloks, Ton; Kratsch, Dieter (1995), "Treewidth and pathwidth of permutation graphs", SIAM Journal on Discrete Mathematics, 8 (4): 606–616, doi:10.1137/S089548019223992X.

- Brandstädt, Andreas; Le, Van Bang; Spinrad, Jeremy P. (1999), Graph Classes: A Survey, SIAM Monographs on Discrete Mathematics and Applications, ISBN 0-89871-432-X.

- Dushnik, Ben; Miller, Edwin W. (1941), "Partially ordered sets" (PDF), American Journal of Mathematics, 63 (3): 600–610, doi:10.2307/2371374, JSTOR 2371374.

- Golumbic, Martin C. (1980), Algorithmic Graph Theory and Perfect Graphs, Computer Science and Applied Mathematics, Academic Press, p. 159.

- McConnell, Ross M.; Spinrad, Jeremy P. (1999), "Modular decomposition and transitive orientation", Discrete Mathematics, 201 (1–3): 189–241, arXiv:1010.5447, doi:10.1016/S0012-365X(98)00319-7, MR 1687819.

- Spinrad, Jeremy P.; Brandstädt, Andreas; Stewart, Lorna K. (1987), "Bipartite permutation graphs", Discrete Applied Mathematics, 18: 279–292, doi:10.1016/s0166-218x(87)80003-3.