Penelope Barker

Penelope Barker (June 17, 1728 – 1796) was an activist in the American Revolution who organized a boycott of British goods in 1774 known as the Edenton Tea Party.[1]

Penelope Barker | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Born | Penelope Pagett June 17th, 1728 |

| Died | 1796 (aged 67–68) |

| Occupation | Activist during the American Revolution |

| Spouse(s) | John Hodgson, James Craven, Thomas Barker |

Early life and family

Penelope Barker was born on June 17, 1728 in Edenton, North Carolina. She was one of three daughters to Samuel Padgett, a physician, and Elizabeth Blount. Barker outlived many of her spouses and family members. For example, her father and sister, Elizabeth, died consecutively, leaving her to raise Elizabeth's children. At the young age of 17, Barker married her deceased sister's husband, John Hodgson, in 1745. Only two years later, John died, leaving her with two of her own sons and her sister's three children.[2] In 1751, Barker remarried to the wealthy James Craven, who was a planter and farmer. When he died in 1755, she inherited all of his estate and became the richest woman in the Province of North Carolina. For the third and final time, she married Thomas Barker, an attorney in Edenton, who was 16 years older than her. They had three children who all died before their first birthday. Thomas sailed to England many times as a representative of North Carolina. In 1761, he journeyed there and was unable to return for many years due to the British blockade of American ships.[2] While her husband was unable to return home from London, Barker managed their estates and home. Thomas returned in 1778; later, in 1782, he and his wife built a home, known today as the Barker House. Barker outlived her husband by seven years, dying in 1796. She and her husband are buried alongside each other in the Johnston family graveyard at Hayes Plantation, near Edenton.[3]

Women in the American Revolution

During the time of the American Revolution, women - being the main consumers of British teas and textiles - boycotted all British imports and even formed groups to encourage other women to do so in order to support the rebellion. They signed resolutions, like the Edenton Tea Party, and created their own teas from mulberry leaves, lavender, and locally grown herbs.

Involvement and Tea Party

Barker was known as a patriot of the Revolution and ten months after the famous Boston Tea Party, she organized a Tea Party of her own. Penelope wrote a statement proposing a boycott on British goods. Followed by 50 other women, the Edenton Tea Party was created. On October 25, 1774, Barker and her supporters met at the house of Elizabeth King to sign the Edenton Tea Party resolution. The resolution stated "We, the aforesaid Lady's will not promote ye wear of any manufacturer from England until such time that all acts which tend to enslave our Native country shall be repealed".[2] This is one of the first ever recorded women's political demonstrations in the Americas.

Backlash

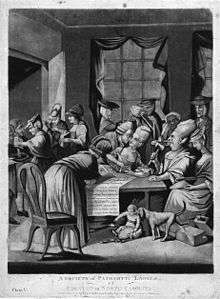

Barker sent this petition to London, which caused much controversy about the women involved. While it was condoned in the colonial press, the women were mocked in the London papers. A political cartoon was published and released in London. The cartoon portrayed the women as bad mothers with loose morals and received misogynistic ridicule.[4] Men in London stated that these women were stepping out of their expected gender roles.

References

- Howat, Kenna (2017), "Mythbusting the Founding Mothers", National Women's History Museum

- "Penelope Pagett Barker – History of American Women". womenhistoryblog.com. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- Martin, Jr., Michael G. (1979). "Barker, Penelope". NCpedia. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- Penelope Barker (1728–1796) National Women's History Museum entry. Accessed September 2014

- Diane Silcox-Jarrett, Penelope Barker, Leader of the Edenton Tea Party in Heroines of the American Revolution, America's Founding Mothers (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Green Angle Press, 1998).

- Edenton History FAQs," Edenton North Carolina, n.d., https://web.archive.org/web/20091015151248/http://www.edenton.com/history/miscfact.htm (21 June 2006).

- Collins, Gail. America's Women: Four Hundred Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates, and Heroines (New York: HarperCollins, 2003).

- Cotton, Sally S. History of the North Carolina Federation of Women's Clubs, 1901–1925 (Raleigh, North Carolina, 1925) reprinted on "The Role of Women in NC History," Campbell University. http://www.campbell.edu/faculty/faulkner/NCHist33210-12.pdf.

- Garrison, Webb. Great Stories of the American Revolution: Unusual, Interesting Stories of the Exhilarating Era When a Nation was Born. (Rutledge Hill Press, 1993).Mitchell, Maggie. "Treasonous Tea: The Edenton Tea Party of 1774." Order No. 10009340 Liberty University, 2015. Ann Arbor: ProQuest. Web. 20 Nov. 2016.

- Michals, Debra. "Penelope Barker". National Women's History Museum. 2015.

- Mitchell, Maggie. "Treasonous Tea: The Edenton Tea Party of 1774." Order No. 10009340 Liberty University, 2015. Ann Arbor: ProQuest. Web. 20 Nov. 2016.