Pelvic girdle pain

Pelvic girdle pain (abbreviated PGP) is a pregnancy discomfort that causes pain, instability and limitation of mobility and functioning in any of the three pelvic joints. PGP has a long history of recognition, mentioned by Hippocrates[1] and later described in medical literature by Snelling.[2]

The affection appears to consist of relaxation of the pelvic articulations, becoming apparent suddenly after parturition or gradually during pregnancy and permitting a degree of mobility of the pelvic bones which effectively hinders locomotion and gives rise to the most peculiar and alarming sensations.

— Snelling (1870), [2]

| Pelvic girdle pain | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | OB/GYN |

Classification

Prior to the 20th century, specialists of pregnancy-related PGP used varying terminologies. It is now referred to as Pregnancy Related Pelvic Girdle Pain that may incorporate the following conditions:

- Diastasis of the Symphysis Pubis(DSP)

- Symphysis pubis dysfunction(SPD)

- Pelvic Joint Syndrome

- Physiological Pelvic Girdle Relaxation

- Symptom Giving Pelvic Girdle Relaxation

- Posterior Pelvic Pain

- Pelvic Arthropathy

- Inferior Pubic Shear/ Superior Pubic Shear /Symphyseal Shear

- Symphysiolysis

- Osteitis pubis (usually postpartum)

- Sacroiliitis

- One-sided Sacroiliac Syndrome /Double Sided Sacroiliac Syndrome

- Hypermobility

"The classification between hormonal and mechanical pelvic girdle instability is no longer used. For treatment and/or prognosis it makes no difference whether the complaints started during pregnancy or after childbirth." Mens (2005)[3]

Signs and symptoms

A combination of postural changes, baby, unstable pelvic joints under the influence of pregnancy hormones, and changes in the centre of gravity can all add to the varying degrees of pain or discomfort. In some cases it can come on suddenly or following a fall, sudden abduction of the thighs (opening too wide too quickly) or an action that has strained the joint.

PGP can begin as early as the first trimester of pregnancy. Pain is usually felt low down over the symphyseal joint, and this area may be extremely tender to the touch. Pain may also be felt in the hips, groin and lower abdomen and can radiate down the inner thighs. Women suffering from PGP may begin to waddle or shuffle, and may be aware of an audible clicking sound coming from the pelvis. PGP can develop slowly during pregnancy, gradually gaining in severity as the pregnancy progresses.

During pregnancy and postpartum, the symphyseal gap can be felt moving or straining when walking, climbing stairs or turning over in bed; these activities can be difficult or even impossible. The pain may remain static, e.g., in one place such as the front of the pelvis, producing the feeling of having been kicked; in other cases it may start in one area and move to other areas. It is also possible that a woman may experience a combination of symptoms.

Any weight bearing activity has the potential of aggravating an already unstable pelvis, producing symptoms that may limit the ability of the woman to carry out many daily activities. She may experience pain involving movements such as dressing, getting in and out of the bath, rolling in bed, climbing the stairs or sexual activity. Pain may also be present when lifting, carrying, pushing or pulling.

The symptoms (and their severity) experienced by women with PGP vary, but include:

- Present swelling and/or inflammation over joint.

- Difficulty lifting leg.

- Pain pulling legs apart.

- Inability to stand on one leg.

- Inability to transfer weight through pelvis and legs.

- Pain in hips and/or restriction of hip movement.

- Transferred nerve pain down leg.

- Can be associated with bladder and/or bowel dysfunction.

- A feeling of the symphysis pubis giving way.

- Stooped back when standing.

- Malalignment of pelvic and/or back joints.

- Struggle to sit or stand.

- Pain may also radiate down the inner thighs.

- Waddling or shuffling gait.

- Audible ‘clicking’ sound coming from the pelvis.

Severity

The severity and instability of the pelvis can be measured on a three level scale.

Pelvic type 1:The pelvic ligaments support the pelvis sufficiently. Even when the muscles are used incorrectly, no complaints will occur when performing everyday activities. This is the most common situation in persons who have never been pregnant, who have never been in an accident, and who are not hypermobile.

Pelvic type 2:The ligaments alone do not support the joint sufficiently. A coordinated use of muscles around the joint will compensate for ligament weakness. In case the muscles around the joint do not function, the patient will experience pain and weakness when performing everyday activities. This type often occurs after giving birth to a child weighing 3000 grams or more, in cases of hypermobility, and sometimes after an accident involving the pelvis. Type 2 is the most common form of pelvic instability. Treatment is based on learning how to use the muscles around the pelvis more efficiently.

Pelvic type 3:The ligaments do not support the joint sufficiently. This is a serious situation whereby the muscles around the joint are unable to compensate for ligament weakness. This type of pelvic instability usually only occurs after an accident, or occasionally after a (small) accident in combination with giving birth. Sometimes a small accident occurring long before giving birth is forgotten so that the pelvic instability is attributed only to the childbirth. Although the difference between Type 2 and 3 is often difficult to establish, in case of doubt an exercise program may help the patient. However, if Pelvic Type 3 has been diagnosed then invasive treatment is the only option: in this case parts of the pelvis are screwed together. (Mens 2005)[3]

Psychosocial impact

PGP in pregnancy seriously interferes with participation in society and activities of daily life; the average sick leave due to posterior pelvic pain during pregnancy is 7 to 12 weeks.[4]

In some cases women with PGP may also experience emotional problems such as anxiety over the cause of pain, resentment, anger, lack of self-esteem, frustration and depression; she is three times more likely to suffer postpartum depressive symptoms.[5] Other psychosocial risk factors associated with woman experiencing PGP include higher level of stress, low job satisfaction and poorer relationship with spouse.[6]

Causes

Sometimes there is no obvious explanation for the cause of PGP but usually there is a combination of factors such as:

- The pelvic joints moving unevenly.

- A change in the activity of the muscles in the pelvis, hip, abdomen, back and pelvic floor.

- A history of pelvic trauma.

- The position of the baby altering the loading stresses on the pelvic ligaments and joints.

- Strenuous work.[7]

- Previous lower back pain.

- Previous pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy.

- Hypermobility, genetical ability to stretch joints beyond normal range.

- An event during the pregnancy or birth that caused injury or strain to the pelvic joints or rupture of the fibrocartilage.

- The occurrence of PGP is associated with twin pregnancy, first pregnancy and a higher age at first pregnancy.[8]

Mechanism

Pregnancy related Pelvic Girdle Pain (PGP) can be either specific (trauma or injury to pelvic joints or genetical i.e. connective tissue disease) and non-specific. PGP disorder is complex and multi-factorial and likely to be also represented by a series of sub-groups driven by pain varying from peripheral or central nervous system,[9] altered laxity/stiffness of muscles,[10] laxity to injury of tendinous/ligamentous structures[11] to ‘mal-adaptive’ body mechanics.[12]

Pregnancy begins the physiological changes through a pattern of hormonal secretion and signal transduction thus initiating the remodelling of soft tissues, cartilage and ligaments. Over time, the ligaments could be stretched either by injury or excess strain and in turn may cause PGP.

Anatomy

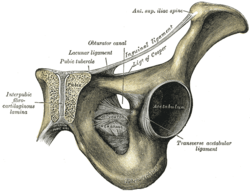

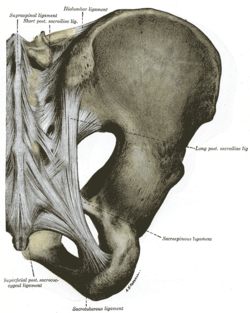

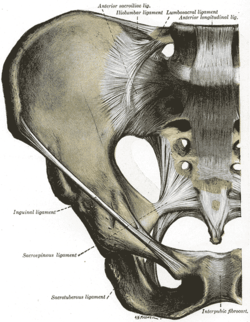

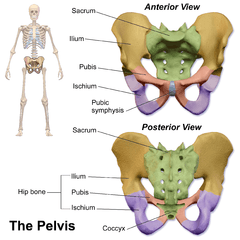

The pelvis is the largest bony part of the skeleton and contains three joints: the pubic symphysis, and two sacroiliac joints. A highly durable network of ligaments surrounds these joints giving them tremendous strength.

The pubic symphysis has a fibrocartilage joint which may contain a fluid filled cavity and is avascular; it is supported by the superior and arcuate ligaments. The sacroiliac joints are synovial, but their movement is restricted throughout life and they are progressively obliterated by adhesions. The nature of the bony pelvic ring with its three joints determines that no one joint can move independently of the other two.[13]

Pubic symphysis

Pubic symphysis Posterior Sacroiliac joint

Posterior Sacroiliac joint Anterior Sacroiliac joint

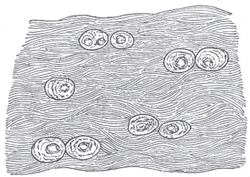

Anterior Sacroiliac joint White fibrocartilage from an intervertebral fibrocartilage.

White fibrocartilage from an intervertebral fibrocartilage. Human pelvis: front and back

Human pelvis: front and back

Relaxin hormone

Relaxin is a hormone produced mainly by the corpus luteum of the ovary and breast, in both pregnant and non-pregnant females. During pregnancy it is also produced by the placenta, chorion, and decidua. The body produces relaxin during menstruation that rises to a peak within approximately 14 days of ovulation and then declines. In pregnant cycles, rather than subsiding, relaxin secretion continues to rise during the first trimester and then again in the final weeks. During pregnancy relaxin has a diverse range of effects, including the production and remodelling of collagen thus increasing the elasticity of muscles, tendons, ligaments and tissues of the birth canal in view of delivery.

Although relaxin's main cellular action in pregnancy is to remodel collagen by biosynthesis (thus facilitating the changes of connective tissue) it does not seem to generate musculoskeletal problems. European Research has determined that relaxin levels are not a predictor of PGP during pregnancy.[14][15][16][17]

Gait changes

The pregnant woman has a different pattern of "gait". The step lengthens as the pregnancy progresses due to weight gain and changes in posture. Both the length and height of the footstep shortens with PGP. Sometimes the foot can turn inwards due to the rotation of the hips when the pelvic joints are unstable. On average, a woman's foot can grow by a half size or more during pregnancy. Pregnancy hormones that are released to adapt the bodily changes also remodel the ligaments in the foot. In addition, the increased body weight of pregnancy, fluid retention and weight gain lowers the arches, further adding to the foot's length and width. There is an increase of load on the lateral side of the foot and the hind foot. These changes may also be responsible for the musculoskeletal complaints of lower limb pain in pregnant women.

During the motion of walking, an upward movement of the pelvis, one side then the other, is required to let the leg follow through. The faster or longer each step the pelvis adjusts accordingly. The flexibility within the knees, ankles and hips are stabilized by the pelvis. Normal gait tends to minimize displacement of centre of gravity whereas abnormal gait through pelvic instability tends to amplify displacement. During pregnancy there may be an increased demand placed on hip abductor, hip extensor, and ankle plantar flexor muscles during walking. To avoid pain on weight bearing structures a very short stance phase and limp occurs on the injured side(s), this is called Antalgic Gait.

Treatment

A number of treatments have some evidence for benefits include an exercise program.[18] Paracetamol (acetaminophen) has not been found effective but is safe.[18] NSAIDs are sometimes effective but should not be used after 30 weeks of pregnancy.[18] There is tentative evidence for acupuncture.[18]

Some pelvic joint trauma will not respond to conservative type treatments and orthopedic surgery might become the only option to stabilize the joints.

Prognosis and epidemiology

For most women, PGP resolves in weeks after delivery but for some it can last for years resulting in a reduced tolerance for weight bearing activities. PGP can take from 11 weeks, 6 months or even up to 2 years postpartum to subside.[19] However, some research supports that the average time to complete recovery is 6.25 years, and the more severe the case is, the longer recovery period.[20]

Overall, about 45% of all pregnant women and 25% of all women postpartum suffer from PGP.[21] During pregnancy, serious pain occurs in about 25%, and severe disability in about 8% of patients. After pregnancy, problems are serious in about 7%.[22] There is no correlation between age, culture, nationality and numbers of pregnancies that determine a higher incidence of PGP.[23][24]

If a woman experiences PGP during one pregnancy, she is more likely to experience it in subsequent pregnancies; but the severity cannot be determined.[25]

References

- Owens Kelly, Pearson Anne, Mason Gerald (2002). "Pubic Symphysis Separation". Fetal and Maternal Medicine Review. 13: 141–155. doi:10.1017/s0965539502000244.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Pain In Childbearing, Key Issues In Management, Margaret Yerby, Lesley Page.

- About Pelvic Girdle Instability. Definition and Concept. Jan M.A. Mens.

- Noren Lotta RPT; Ostgaard Solveig; Nielsen Thorkild F; Ostgaard Hans C (1997). "Reduction of Sick Leave for Lumbar Back and Posterior Pelvic Pain in Pregnancy". Spine. 22 (18): 2157–2160. doi:10.1097/00007632-199709150-00013.

- Gutke A, Josefsson A, Oberg B (Jun 2007). "Pelvic girdle pain and lumbar pain in relation to postpartum depressive symptoms". Spine. 32 (13): 1430–6. doi:10.1097/brs.0b013e318060a673.

- Albert HB, Godskesen M, Korsholm L, Westergaard JG (2006). "Risk factors in developing pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain". Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 85 (5): 539–44. doi:10.1080/00016340600578415.

- Juhl Mette; Kragh Andersen Per; Olsen Jørn; Nybo Andersen Anne-Marie (2005). "Psychosocial and Physical Work Environment and Risk of Pelvic Pain in Pregnancy. A Study within the Danish National Birth Cohort". Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 59 (7): 580–585. doi:10.1136/jech.2004.029520. PMC 1757090. PMID 15965142.

- Mens JM, Vleeming A, Stoeckart R, Stam HJ, Snijders CJ (Jun 1996). "Understanding peripartum pelvic pain. Implications of a patient survey". Spine. 21 (11): 1363–9. doi:10.1097/00007632-199606010-00017. hdl:1765/71226.

- Diagnosis and classification of pelvic girdle pain disorders—Part 1: A mechanism based approach within a biopsychosocial framework Manual Therapy, Volume 12, Issue 2, May 2007, Peter B. O’Sullivan and Darren J. Beales.

- European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain.Eur Spine J. 2008 Feb 8 Vleeming A, Albert HB, Ostgaard HC, Sturesson B, Stuge B.

- Possible role of the long dorsal sacroiliac ligament in women with peripartum pelvic pain. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica Volume 81 Issue 5 Page 430-436, May 2002, Andry Vleeming, Haitze J. de Vries, Jan M. A Mens, Jan-Paul van Wingerden

- Diagnosis and classification of pelvic girdle pain disorders—Part 1: A mechanism based approach within a biopsychosocial framework. Manual Therapy, Volume 12, Issue 2, May 2007, Pages 86-97 Peter B. O’Sullivan, and Darren J. Bealesa.

- SPD: The Clinical Presentation, Prevalence, Aetiology, Risk Factors and Morbidity. Malcolm Griffiths.

- Petersen LK, Hvidman L, Uldbjerg N (1994). "Normal Serum Relaxin in Women with Disabling Pelvic Pain During Pregnancy". Gynecol Obstet Invest. 38 (1): 21–3. doi:10.1159/000292438. PMID 7959320.

- Björklund K, Bergström S, Nordström ML, Ulmsten U (Apr 2000). "Symphyseal Distention in Relation to Serum Relaxin Levels and Pelvic Pain in Pregnancy". Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 79 (4): 269–75. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0412.2000.079004269.x. PMID 10746841.

- Hansen A, Jensen DV, Larsen E, Wilken-Jensen C, Petersen LK (Mar 1996). "Relaxin is not related to symptom-giving pelvic girdle relaxation in pregnant women". Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 75 (3): 245–9. doi:10.3109/00016349609047095. PMID 8607337.

- Albert H, Godskesen M, Westergaard JG, Chard T, Gunn L (Jul 1997). "Circulating levels of relaxin are normal in pregnant women with pelvic pain". Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 74 (1): 19–22. doi:10.1016/s0301-2115(97)00076-6. PMID 9243195.

- Verstraete, EH; Vanderstraeten, G; Parewijck, W (2013). "Pelvic Girdle Pain during or after Pregnancy: a review of recent evidence and a clinical care path proposal". Facts, Views & Vision in ObGyn. 5 (1): 33–43. PMC 3987347. PMID 24753927.

- Larsen EC, Wilken-Jensen C, Hansen A, Jensen DV, Johansen S, Minck H, Wormslev M, Davidsen M, Hansen TM (Feb 1999). "Symptom-Giving Pelvic Girdle Relaxation in Pregnancy. I: Prevalence and Risk Factors". Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 78 (2): 105–10. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0412.1999.780206.x. PMID 10023871.

- Symptom-giving p Pelvic Girdle Relaxation of Pregnancy, Postnatal Pelvic Joint Syndrome and Developmental Dysplasia of Hip. ISSN 0001-6349 Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1997; 76: 760-764. Alastair H. MacLennan, Suzanna C. MacLennan.

- W. H. Wu, O. G. Meijer, K. Uegaki, J. M. A. Mens, J. H. van Dieën, P. I. J. M. Wuisman, H. C. Östgaard. "Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain (PPP), I: Terminology, clinical presentation, and prevalence European Spine Journal Vol 13, No. 7 / Nov. 2004

- Elden H; Ladfors L; Olsen M Fagevik; Östgaard H-C; Hagber H (2005). "Effects of acupuncture and stabilising exercises as adjunct to standard treatment in pregnant women with pelvic girdle pain: randomised single blind controlled trail". BMJ. 330 (7494): 761. doi:10.1136/bmj.38397.507014.e0. PMC 555879. PMID 15778231.

- Stones R William; Vits Kathleen (2005). "Pelvic Girdle Pain in Pregnancy". BMJ. 331 (7511): 249–250. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7511.249. PMC 1181256. PMID 16051994.

- Bjorklund K, Bergstrom S (Jan 2000). "Is Pelvic Pain a Welfare Complaint?". Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 79 (1): 24–30. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0412.2000.079001024.x. PMID 10646812.

- Kumle Merethe; Weiderpass Elisabete; Alsaker Elin; Lund Eiliv (2004). "Use of Hormonal Contraceptives and Occurrence of Pregnancy-Related Pelvic Pain: A Prospective Cohort Study in Norway". BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 4 (1): 11. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-4-11. PMC 446199. PMID 15212688.

Further reading

- Recommendations for the Nomenclature of Receptors for Relaxin Family Peptides Pharmacol Rev 58:7-31,2006 Ross A. Bathgate, Richard Ivell, Barbara M. Sanborn, O. David Sherwood and Roger J. Summers