Peg solitaire

Peg solitaire (or Solo Noble) is a board game for one player involving movement of pegs on a board with holes. Some sets use marbles in a board with indentations. The game is known simply as Solitaire in the United Kingdom where the card games are called Patience. It is also referred to as Brainvita (especially in India).

The first evidence of the game can be traced back to the court of Louis XIV, and the specific date of 1687, with an engraving made ten years later by Claude Auguste Berey of Anne de Rohan-Chabot, Princess of Soubise, with the puzzle by her side. The August 1687 edition of the French literary magazine Mercure galant contains a description of the board, rules and sample problems. This is the first known reference to the game in print.

The standard game fills the entire board with pegs except for the central hole. The objective is, making valid moves, to empty the entire board except for a solitary peg in the central hole.

Board

There are two traditional boards ('.' as an initial peg, 'o' as an initial hole):

| English | European |

|---|---|

· · ·

· · ·

· · · · · · ·

· · · o · · ·

· · · · · · ·

· · ·

· · · |

· · ·

· · · · ·

· · · · · · ·

· · · o · · ·

· · · · · · ·

· · · · ·

· · · |

Play

A valid move is to jump a peg orthogonally over an adjacent peg into a hole two positions away and then to remove the jumped peg.

In the diagrams which follow, · indicates a peg in a hole, * emboldened indicates the peg to be moved, and o indicates an empty hole. A blue ¤ is the hole the current peg moved from; a red * is the final position of that peg, a red o is the hole of the peg that was jumped and removed.

Thus valid moves in each of the four orthogonal directions are:

* · o → ¤ o * Jump to right

o · * → * o ¤ Jump to left

* ¤ · → o Jump down o *

o * · → o Jump up * ¤

On an English board, the first three moves might be:

· · · · · · · · · · · ·

· * · · ¤ · · o · · * ·

· · · · · · · · · · o · · · · ¤ o * · · · · o o o · · ·

· · · o · · · · · · * · · · · · · · · · · · · · ¤ · · ·

· · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·

· · · · · · · · · · · ·

· · · · · · · · · · · ·

Strategy

There are many different solutions to the standard problem, and one notation used to describe them assigns letters to the holes:

English European

a b c a b c

d e f y d e f z

g h i j k l m g h i j k l m

n o p x P O N n o p x P O N

M L K J I H G M L K J I H G

F E D Z F E D Y

C B A C B A

This mirror image notation is used, amongst other reasons, since on the European board, one set of alternative games is to start with a hole at some position and to end with a single peg in its mirrored position. On the English board the equivalent alternative games are to start with a hole and end with a peg at the same position.

There is no solution to the European board with the initial hole centrally located, if only orthogonal moves are permitted. This is easily seen as follows, by an argument from Hans Zantema. Divide the positions of the board into A, B and C positions as follows:

A B C

A B C A B

A B C A B C A

B C A B C A B

C A B C A B C

B C A B C

A B C

Initially with only the central position free, the number of covered A positions is 12, the number of covered B positions is 12, and also the number of covered C positions is 12. After every move the number of covered A positions increases or decreases by one, and the same for the number of covered B positions and the number of covered C positions. Hence after an even number of moves all these three numbers are even, and after an odd number of moves all these three numbers are odd. Hence a final position with only one peg cannot be reached, since that would require that one of these numbers is one (the position of the peg, one is odd), while the other two numbers are zero, hence even.

There are, however, several other configurations where a single initial hole can be reduced to a single peg.

A tactic that can be used is to divide the board into packages of three and to purge (remove) them entirely using one extra peg, the catalyst, that jumps out and then jumps back again. In the example below, the * is the catalyst.:

* · o ¤ o * o * · * o ¤ · → · → o → o · · ¤ o

This technique can be used with a line of 3, a block of 2·3 and a 6-peg L shape with a base of length 3 and upright of length 4.

Other alternate games include starting with two empty holes and finishing with two pegs in those holes. Also starting with one hole here and ending with one peg there. On an English board, the hole can be anywhere and the final peg can only end up where multiples of three permit. Thus a hole at a can only leave a single peg at a, p, O or C.

Studies on peg solitaire

A thorough analysis of the game is known.[1] This analysis introduced a notion called pagoda function which is a strong tool to show the infeasibility of a given, generalized, peg solitaire, problem.

A solution for finding a pagoda function, which demonstrates the infeasibility of a given problem, is formulated as a linear programming problem and solvable in polynomial time.[2]

A paper in 1990 dealt with the generalized Hi-Q problems which are equivalent to the peg solitaire problems and showed their NP-completeness.[3]

A 1996 paper formulated a peg solitaire problem as a combinatorial optimization problem and discussed the properties of the feasible region called 'a solitaire cone'.[4]

In 1999 peg solitaire was completely solved on a computer using an exhaustive search through all possible variants. It was achieved making use of the symmetries, efficient storage of board constellations and hashing.[5]

In 2001 an efficient method for solving peg solitaire problems was developed.[2]

An unpublished study from 1989 on a generalized version of the game on the English board showed that each possible problem in the generalized game has 29 possible distinct solutions, excluding symmetries, as the English board contains 9 distinct 3×3 sub-squares. One consequence of this analysis is to put a lower bound on the size of possible "inverted position" problems, in which the cells initially occupied are left empty and vice versa. Any solution to such a problem must contain a minimum of 11 moves, irrespective of the exact details of the problem.

It can be proved using abstract algebra that there are only 5 fixed board positions where the game can successfully end with one peg.[6]

Solutions to the English game

The shortest solution to the standard English game involves 18 moves, counting multiple jumps as single moves:

| Shortest solution to English peg solitaire |

|---|

e-x l-j c-k

· · · · · · · · · · · ¤

· * · · ¤ · · o · · o o

· · · · · · · · · · o · · · · · · * o ¤ · · · · · * o ·

· · · o · · · · · · * · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·

· · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·

· · · · · · · · · · · ·

· · · · · · · · · · · ·

P-f D-P G-I J-H

· · o · · o · · o · · o

· o * · o · · o · · o ·

· · · · o o · · · · · o o · · · · · o o · · · · · o o ·

· · · · ¤ · · · · · · * · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·

· · · · · · · · · · · o · · · · · · * o ¤ · · · ¤ o * o

· · · · · ¤ · · o · · o

· · · · · · · · · · · ·

m-G-I i-k g-i L-J-H-l-j-h

· · o · · o · · o · · o

· o · · o · · o · · o ·

· · · · o o ¤ · · ¤ o * o o ¤ o * o · o o o * o o o o o

· · · · · · o · · · · · · o · · · · · · o · · · · · o o

· · · o * o o · · · o · o o · · · o · o o · ¤ o o o o o

· · o · · o · · o · · o

· · · · · · · · · · · ·

C-K p-F A-C-K M-g-i

· · o · · o · · o · · o

· o · · o · · o · · o ·

o · o o o o o o · o o o o o o · o o o o o o o * o o o o

· · · · · o o · · ¤ · · o o · · o · · o o o · o · · o o

· o * o o o o · o o o o o o · o * o o o o ¤ o · o o o o

o · o * · o o · o o · o

¤ · · o · · o o ¤ o o o

a-c-k-I d-p-F-D-P-p o-x

¤ o o o o o o o o

· o o ¤ o o o o o

o o · o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o

o · o · o o o o · * o o o o o ¤ o * o o o

o o · o * o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o

o · o o o o o o o

o o o o o o o o o

The order of some of the moves can be exchanged. Note that if you instead think of * as a hole and o as a peg, you can solve the puzzle by following the solution in reverse, starting from the last picture, going towards the first. However, this requires more than 18 moves. |

This solution was found in 1912 by Ernest Bergholt and proven to be the shortest possible by John Beasley in 1964.[7]

This solution can also be seen on a page that also introduces the Wolstenholme notation, which is designed to make memorizing the solution easier.

Other solutions include the following list. In these, the notation used is

- List of starting holes

- Colon

- List of end target pegs

- Equals sign

- Source peg and destination hole (the pegs jumped over are left as an exercise to the reader)

- , or / (a slash is used to separate 'chunks' such as a six-purge out)

x:x=ex,lj,ck,Pf,DP,GI,JH,mG,GI,ik,gi,LJ,JH,Hl,lj,jh,CK,pF,AC,CK,Mg,gi,ac,ck,kI,dp,pF,FD,DP,Pp,ox x:x=ex,lj,xe/hj,Ki,jh/ai,ca,fd,hj,ai,jh/MK,gM,hL,Fp,MK,pF/CK,DF,AC,JL,CK,LJ/PD,GI,mG,JH,GI,DP/Ox j:j=lj,Ik,jl/hj,Ki,jh/mk,Gm,Hl,fP,mk,Pf/ai,ca,fd,hj,ai,jh/MK,gM,hL,Fp,MK,pF/CK,DF,AC,JL,CK,LJ/Jj i:i=ki,Jj,ik/lj,Ik,jl/AI,FD,CA,HJ,AI,JH/mk,Hl,Gm,fP,mk,Pf/ai,ca,fd,hj,ai,jh/gi,Mg,Lh,pd,gi,dp/Ki e:e=xe/lj,Ik,jl/ck,ac,df,lj,ck,jl/GI,lH,mG,DP,GI,PD/AI,FD,CA,JH,AI,HJ/pF,MK,gM,JL,MK,Fp/hj,ox,xe d:d=fd,xe,df/lj,ck,ac,Pf,ck,jl/DP,KI,PD/GI,lH,mG,DP,GI,PD/CK,DF,AC,LJ,CK,JL/MK,gM,hL,pF,MK,Fp/pd b:b=jb,lj/ck,ac,Pf,ck/DP,GI,mG,JH,GI,PD/LJ,CK,JL/MK,gM,hL,pF,MK,Fp/xo,dp,ox/xe/AI/BJ,JH,Hl,lj,jb b:x=jb,lj/ck,ac,Pf,ck/DP,GI,mG,JH,GI,PD/LJ,CK,JL/MK,gM,hL,pF,MK,Fp/xo,dp,ox/xe/AI/BJ,JH,Hl,lj,ex a:a=ca,jb,ac/lj,ck,jl/Ik,pP,KI,lj,Ik,jl/GI,lH,mG,DP,GI,PD/CK,DF,AC,LJ,CK,JL/dp,gi,pd,Mg,Lh,gi/ia a:p=ca,jb,ac/lj,ck,jl/Ik,pP,KI,lj,Ik,jl/GI,lH,mG,DP,GI,PD/CK,DF,AC,LJ,CK,JL/dp,gi,pd,Mg,Lh,gi/dp

Brute force attack on standard English peg solitaire

The only place it is possible to end up with a solitary peg is the centre, or the middle of one of the edges; on the last jump, there will always be an option of choosing whether to end in the centre or the edge.

Following is a table over the number (Possible Board Positions) of possible board positions after n jumps, and the possibility of the same pawn moved to make a further jump (No Further Jumps).

NOTE: If one board position can be rotated and/or flipped into another board position, the board positions are counted as identical.

|

|

|

|

Since there can only be 31 jumps, modern computers can easily examine all game positions in a reasonable time.

The above sequence "PBP" has been entered as A112737 in OEIS. Note that the total number of reachable board positions (sum of the sequence) is 23,475,688, while the total number of possible board positions is 8.589.934.590 (33bit-1) (2^33) , So only about 2.2% of all possible board positions can be reached starting with the center vacant.

It is also possible to generate all board positions. The results below have been obtained using

the mcrl2 toolset (see the peg_solitaire example in the distribution).

|

|

|

|

In the results below It is generate all board positions really reached starting with the center vacant and finish in central hole.

|

|

|

|

Solutions to the European game

There are 3 initial non-congruent positions that have solutions.[8] These are:

1)

0 1 2 3 4 5 6

0 o · ·

1 · · · · ·

2 · · · · · · ·

3 · · · · · · ·

4 · · · · · · ·

5 · · · · ·

6 · · ·

Possible solution: [2:2-0:2, 2:0-2:2, 1:4-1:2, 3:4-1:4, 3:2-3:4, 2:3-2:1, 5:3-3:3, 3:0-3:2, 5:1-3:1, 4:5-4:3, 5:5-5:3, 0:4-2:4, 2:1-4:1, 2:4-4:4, 5:2-5:4, 3:6-3:4, 1:1-1:3, 2:6-2:4, 0:3-2:3, 3:2-5:2, 3:4-3:2, 6:2-4:2, 3:2-5:2, 4:0-4:2, 4:3-4:1, 6:4-6:2, 6:2-4:2, 4:1-4:3, 4:3-4:5, 4:6-4:4, 5:4-3:4, 3:4-1:4, 1:5-1:3, 2:3-0:3, 0:2-0:4]

2)

0 1 2 3 4 5 6

0 · · ·

1 · · o · ·

2 · · · · · · ·

3 · · · · · · ·

4 · · · · · · ·

5 · · · · ·

6 · · ·

Possible solution: [1:1-1:3, 3:2-1:2, 3:4-3:2, 1:4-3:4, 5:3-3:3, 4:1-4:3, 2:1-4:1, 2:6-2:4, 4:4-4:2, 3:4-1:4, 3:2-3:4, 5:1-3:1, 4:6-2:6, 3:0-3:2, 4:5-2:5, 0:2-2:2, 2:6-2:4, 6:4-4:4, 3:4-5:4, 2:3-2:1, 2:0-2:2, 1:4-3:4, 5:5-5:3, 6:3-4:3, 4:3-4:1, 6:2-4:2, 3:2-5:2, 4:0-4:2, 5:2-3:2, 3:2-1:2, 1:2-1:4, 0:4-2:4, 3:4-1:4, 1:5-1:3, 0:3-2:3]

and 3)

0 1 2 3 4 5 6

0 · · ·

1 · · · · ·

2 · · · o · · ·

3 · · · · · · ·

4 · · · · · · ·

5 · · · · ·

6 · · ·

Possible solution: [2:1-2:3, 0:2-2:2, 4:1-2:1, 4:3-4:1, 2:3-4:3, 1:4-1:2, 2:1-2:3, 0:4-0:2, 4:4-4:2, 3:4-1:4, 6:3-4:3, 1:1-1:3, 4:6-4:4, 5:1-3:1, 2:6-2:4, 1:4-1:2, 0:2-2:2, 3:6-3:4, 4:3-4:1, 6:2-4:2, 2:3-2:1, 4:1-4:3, 5:5-5:3, 2:0-2:2, 2:2-4:2, 3:4-5:4, 4:3-4:1, 3:0-3:2, 6:4-4:4, 4:0-4:2, 3:2-5:2, 5:2-5:4, 5:4-3:4, 3:4-1:4, 1:5-1:3]

Board variants

Peg solitaire has been played on other size boards, although the two given above are the most popular. It has also been played on a triangular board, with jumps allowed in all 3 directions. As long as the variant has the proper "parity" and is large enough, it will probably be solvable.

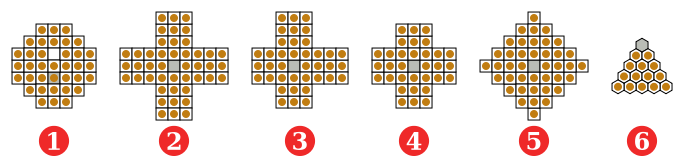

(1) French (European) style, 37 holes, 17th century;

(2) J. C. Wiegleb, 1779, Germany, 45 holes;

(3) Asymmetrical 3-3-2-2 as described by George Bell, 20th century;

(4) English style (standard), 33 holes;

(5) Diamond, 41 holes;

(6) Triangular, 15 holes.

Grey = the hole for the survivor.

A common triangular variant has five pegs on a side. A solution where the final peg arrives at the initial empty hole is not possible for a hole in one of the three central positions. An empty corner-hole setup can be solved in ten moves, and an empty midside-hole setup in nine (Bell 2008):

| Shortest solution to triangular variant |

|---|

|

* = peg to move next; ¤ = hole created by move; o = jumped peg removed; * = hole filled by jumping; · · · * ¤ · · · · · · · * o ¤ · · · · · · * · · ¤ · · * o · · · · · · · · · · · · · · o · · * * · * * · o · · ¤ o * * · o * o ¤ · o · * o · o · · o · o o o o o * * * * ¤ ¤ o o o o o o o o * * o o o o o * o o ¤ ¤ · · ¤ o o o o o o * * o o · o o o o o o * * o · o ¤ ¤ o · o o o o * o o o o ¤ o o * o o |

Video game

On June 26th, 1992, a video game based on peg solitaire was released for the Game Boy. Titled simply "Solitaire", the game was developed by Hect. In North America, DTMC released the game as "Lazlos' Leap".

References

- Berlekamp, E. R.; Conway, J. H.; Guy, R. K. (2001) [1981], Winning Ways for your Mathematical Plays (paperback)

|format=requires|url=(help) (2nd ed.), A K Peters/CRC Press, ISBN 978-1568811307, OCLC 316054929 - Kiyomi, M.; Matsui, T. (2001), "Integer Programming Based Algorithms for Peg Solitaire Problems", Proc. 2nd Int. Conf. Computers and Games (CG 2000): Integer programming based algorithms for peg solitaire problems, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 2063, pp. 229–240, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.65.6244, doi:10.1007/3-540-45579-5_15, ISBN 978-3-540-43080-3

- Uehara, R.; Iwata, S. (1990). "Generalized Hi-Q is NP-complete". Trans. IEICE. 73: 270–273.

- Avis, D.; Deza, A. (2001), "On the solitaire cone and its relationship to multi-commodity flows", Mathematical Programming, 90 (1): 27–57, doi:10.1007/PL00011419

- Eichler; Jäger; Ludwig (1999), c't 07/1999 Spielverderber, Solitaire mit dem Computer lösen (in German), 7, p. 218

- "Mathematics and brainvita", Notes on Mathematics, 28 August 2012, retrieved 6 September 2018

- For Beasley's proof see Winning Ways, volume #4 (second edition).

- Brassine, Michel (December 1981), "Découvrez... le solitaire", Jeux et Stratégie (in French)

Further reading

- Beasley, John D. (1985), The Ins & Outs of Peg Solitaire, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0198532033

- Bell, G. I. (2008), "Solving triangular peg solitaire", Journal of Integer Sequences, 11: Article 08.4.8, arXiv:math.CO/0703865, Bibcode:2007math......3865B.

- Bruijn, N.G. de (1972), "A solitaire game and its relation to a finite field" (PDF), Journal of Recreational Mathematics, 5: 133–137

- Cross, D. C. (1968), "Square solitaire and variations", Journal of Recreational Mathematics, 1: 121–123

- Gardner, M., "Mathematical games", Scientific American 206 (6): 156–166, June 1962; 214 (2): 112–113, Feb. 1966; 214 (5): 127, May 1966.

- Jefferson, Chris; et al. (October 2006), "Modelling and Solving English Peg Solitairet", Computers & Operations Research, 33 (10): 2935–2959, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.5.7805, doi:10.1016/j.cor.2005.01.018

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Peg solitaire. |

- Bogomolny, Alexander, "Peg Solitaire and Group Theory", Interactive Mathematics Miscellany and Puzzles, retrieved 7 September 2018

- White Pixels (24 October 2017), Peg Solitaire: Easy to remember symmetrical solution (video), Youtube

- Play Multiple Versions of Peg Solitaire including English, European, Triangular, Hexagonal, Propeller, Minimum, 4Holes, 5Holes, Easy Pinwheel, Banzai7, Megaphone, Owl, Star and Arrow at pegsolitaire.org