Pavement ant

The pavement ant (Tetramorium caespitum)—also known as the sugar ant in parts of North America[1][note 1]—is an ant native to Europe, which also occurs as an introduced pest in North America. Its common name comes from the fact that colonies in North America usually make their nests under pavement. This is one of the most commonly seen ants in North America, being well adapted to urban and suburban habitats. It is distinguished by one pair of spines on the back, two nodes on the petiole, and grooves on the head and thorax.[2]

| Pavement ant | |

|---|---|

| |

| Tetramorium caespitum worker | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | T. caespitum |

| Binomial name | |

| Tetramorium caespitum | |

During the late spring and early summer, colonies attempt to conquer new areas and often attack nearby enemy colonies. This results in huge sidewalk battles, sometimes leaving thousands of ants dead.

In summer, the ants dig out the sand between the pavements to vent their nests.

Pavement ants were studied on the International Space Station in 2014.[3]

Description

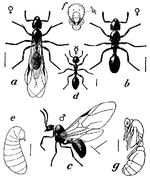

The pavement ant is dark brown to blackish, and 2.5–4 mm long. A colony is composed of workers, alates, and a queen. Workers do have a small stinger, which can cause mild discomfort in humans but is essentially harmless. Alates, or new queen ants and drones, have wings, and are at least twice as large as the workers.

Tetramorium nuptial flights occur in spring and summer; queens and drones leave the nest and find a mate. The drone's only job is to mate with the virgin queens. The dealate, or newly fertilized queen, sheds her wings, finds a suitable nesting location and digs a founding chamber called the clausteral chamber or cell. The queen must raise the first generation of young herself until they are old enough to forage for food. During this period she survives by metabolizing the proteins of her flight muscles. As the eggs hatch and the ants develop, they spend that time, about two to three months, tending to the queen of their colony. They will continue helping in the colony until they are a month old.

Older workers forage for food and defend the colony. They will eat almost anything, including other insects, seeds, honeydew, honey, bread, meats, nuts, ice cream and cheese. Although they do not usually nest inside buildings, they may become a minor nuisance entering homes attracted by food left out. They are also predators of codling moth larvae.[4]

Habitat and nests

Pavement ants build underground nests, preferring areas with little vegetation, and have adapted to urban areas, being found under building foundations, sidewalks, pavements, and patios. Nests occupy an area of 1.2 to 4.8 m2 and are 45 – 90 cm deep. They may be identified by entrance holes surrounded by small crater-shaped mounds of sand in summer. Colonies may have 3,000 to over 10,000 workers, and are usually monogynous, having one queen, or in rare cases two or more.

They defend a territory, estimated at 43 m2 for T. caespitum, and large battles between neighboring unrelated colonies are common, especially in spring when new colonies are establishing their boundaries.

Parasite

T. caespitum serves as host to the workerless and ectoparasitic Tetramorium inquilinum ant.[5] This primitive ant spends its life clinging to the back of a pavement ant, particularly queens.

Notes

- Not to be confused with the banded sugar ant.

References

- "Sugar Ants" (PDF). Washington State University. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- "Pavement ant — Tetramorium caespitum". University of California, Davis. 2004-01-26.

- "Ants Hold Their Own Searching in Space", Discovery News, March 31, 2015

- Tadic, M. (1957). The Biology of the Codling Moth as the Basis for Its Control. Univerzitet U Beogradu.

- Wilson, Edward O. (1963). "The social biology of ants". Annual Review of Entomology. 8: 345–368. doi:10.1146/annurev.en.08.010163.002021.

External links

- National Pest Management Association. "Pavement Ant Fact Sheet". with information on habits, habitat and prevention

- Steve Jacobs, Sr. Extension Associate. "Pavement Ant". College of Agricultural Sciences, Entomology. Penn State University.