Paulette Bernège

Paulette Bernège (1896 – 25 November 1973) was a French journalist, publicist and author who specialized in housework and home economics. She was a pioneer in applying scientific principles to the study of housework and to the design of living spaces and appliances that would make this work more efficient. She thought housework should be measured, analyzed and organized for efficiency in the same way as factory work. Domestic appliances should be used to reduce labor and the home layout should minimize the need to move from one spot to another. Although her ideal home was too expensive for most people in the period before World War II (1939–45), her work led to more efficient designs in French apartments and houses built after the war.

Paulette Bernège | |

|---|---|

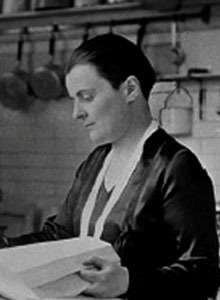

Bernège in her kitchen in 1930 | |

| Born | 1896 Tonneins, Lot-et-Garonne, France |

| Died | 25 November 1973 (aged 77) Miramont-de-Guyenne, Lot-et-Garonne, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Journalist |

| Known for | Housework efficiency theories |

Life

Early years

Paulette Bernège was born in 1896 in Tonneins, Lot-et-Garonne.[1] Her mother was a schoolteacher. Bernège had an excellent education, obtaining a Bachelor of Science, Bachelor of Arts and graduate studies diploma in Philosophy, the highest academic qualification then available to women. She became a journalist, and in 1922 was administrative secretary to the Syndicat de la presse technique and editorial secretary to the review Mon bureau (My Office). This may well be where she became interested in the theories of Frederick Winslow Taylor, which were very popular in the post-war period.[2]

Bernège became the faithful disciple of the Domestic Sciences Movement that Christine Frederick had launched earlier in the United States, which Bernège adapted to French homes. Frederick transferred the concepts of Taylorism from the factory to domestic work. These included suitable tools, rational study of movements and timing of tasks. Scientific standards for housework were derived from scientific standards for workshops, intended to streamline the work of a housewife with or without the help of a cleaning woman.[3] Bernège saw herself as an heiress of Xenophon, René Descartes and Taylor.[4]

Interwar career

The new discipline of household organization was officially baptized in 1923 at the first Salon des arts ménagers (SAM; Household Arts Show).[3] That year Bernège founded the Institut d'organisation ménagère (Institute of Housekeeping Organization) in Nancy.[1] The institute was at first funded by a company that sold domestic appliances.[5] She launched and edited the monthly magazine Mon chez moi (My Home), the institute's organ.[2] In 1924 Bernège presented a paper on household management to the Congress of scientific management in Paris, and founded the Syndicat des appareils ménagers et de l’organisation ménagère (Union of household appliances and home management).[2]

In 1925 the Institut d'organisation ménagère became the Ligue d’organisation ménagère (League for Household Efficiency).[5] Chaired for many years by Bernège, the league aimed to propagate ways to free French housewives from time-consuming chores.[2] In the 1920s and 1930s Bernège wrote articles, spoke at conferences, traveled to other countries to spread her message, ran a school for domestic sciences, and undertook research for industrial companies. She visited the United States, Amsterdam, Glasgow, Brussels, Rome, Prague, Switzerland and Scandinavia.[2] Christine Frederick visited France in April 1927, where Bernège quickly arranged a meeting of the League for Household Efficiency, Association for Household Electric Appliances and Mon Chez Moi, at which the Minister of Housing presided.[6] Frederick wrote, "In France a small but brave attempt is being made by my brilliant self-sacrificing friend, Mlle. Paulette Bernège, who has sponsored and directs that unique home-management periodical, Mon-Chez-Moi which more than perhaps any other in Europe is attempting to educate the woman in modern scientific housekeeping.".[7]

The Comité national de l’organisation française (CNOF) was founded in 1925 by a group of journalists and consulting engineers who saw Taylorism as a way to expand their client base. M. Ponthière, managing editor of Mon bureau, was among the founders, as were prominent engineers such as Henry Louis Le Châtelier and Léon Guillet. Bernège's Institute participated in various congresses on the scientific organization of work that led up to the founding of the CNOF, and in 1929 led to a section in CNOF on domestic economy.[5] Bernege chaired the CNOF domestic economy section.[8] The CNOF evolved into an association of technicians who complied with the demands of the companies that employed them.[5]

In 1928 Bernège published her best-selling De la méthode ménagère (The Household System).[3] In this book Bernège proposed that domestic work is a profession in which the mistress of the house is both a worker and a leader, and proposed that each home be organized by a set of defined processes. The book proposed spending significant time studying and organizing household work, including having the housewife pin a pedometer to her bodice that would record the number and length of steps she takes. This created a comic effect that reviewers exploited, and the ideas that women should claim authority over the home and that improvement of domestic chores was important were considered even more comic. The humorous or sarcastic treatment of the book undermined the serious reputation that the CNOF was attempting to foster, and the domestic economy section of the CNOF remained dormant during the interwar years.[5]

Bernège's also published a booklet in 1928 entitled Si les femmes faisaient les maisons (If Women Made Houses). The tone was somewhat bitter, since the Technical Committee for Dwellings established by Louis Loucheur in preparation for a large-scale program of social housing construction had not consulted the journal Mon chez Moi or the Ligue de l'organisation ménagère in their deliberations.[3] She noted that a housewife in a typical home who climbed a stairway five times per day for forty years did the same work that would be needed to raise the Eiffel Tower by 2.3 metres (7 ft 7 in), and that the distance she traveled between stove and dining table was the same as that from Paris to Lake Baikal. Despite her pleas, the committee only made some basic recommendations on hygiene and function. The 250,000 social houses were made by local artisans with no information about the needs of the occupants, following outdated designs provided by elderly male architects.[2]

In 1930 Bernège established the Ecole de haut enseignement ménager (School of Higher Education in Housework) in Paris.[1] The institute, open to bourgeois girls, gave theoretical rather than practical courses and was mainly intended to train journalists, professors and advertising or marketing experts. The purpose was not spelled out clearly, and the institute did not succeed.[9] Bernège published a series of articles on farming in the Dépêche de Toulouse in 1933, in which she recommended cooperatives as the best approach for rural organization. During World War II (1939–45) she helped reestablish a branch of CNOF in Toulouse in 1940.[10] Bernège made the case that more efficiently organized rural households would help the people of France to go back to their "organic" roots.[11]

Post-war

For almost all French families in the 1930s Bernège was being completely unrealistic in asserting that a modern housewife needed a vacuum cleaner, washing machine and other appliances. Even the few families that could afford these products were unenthusiastic about them. This would change during the postwar recovery of the late 1940s and the 1950s as awareness spread of the contribution of domestic appliances to high living standards in the United States, and of the need for modern designs for the millions of new homes planned in France.[12] The shortage of domestic servants also helped overcome resistance to mechanization.[13]

In the post-war period the Salon des arts ménagers (SAM) played an important role in introducing the innovations championed by Bernège. Experiments in the inter-war period led to new post-war designs in which the kitchen was moved near to the apartment's entrance, close to the living and dining room. The back stairs disappeared. Water, electricity, gas and sewage were now integrated into the design of buildings. The kitchen was relatively small, with a layout designed to let the housewife perform different tasks without moving.[14] In Marcel Gascoin's 8-piece "Logis 1949" display at the SAM the kitchen played a central role and followed the ergonomic principles spelled out by Bernège in the inter-war period.[14] Bernège led a conference at the 1950 SAM on "If Women Designed Home Appliances".[15]

The advice given by the women's magazines of the 1950s showed the strong influence of Bernège's theories. The journal Education ménagère devoted a special issue to her in 1960. It listed her achievement in making society recognize that housework was a profession, domestic appliances were necessities rather than luxuries, and housework should be organized so the woman could free herself from it. It concluded that "Paulette Bernège was a 'pioneer' and women will never be able to thank her enough for what she has done for them."[16] In reality, the theoretical organization proposed by Bernège was still out of reach of most working women in the 1950s, who did not have the required housing, equipment or social support to achieve their aspirations.[17]

Paulette Bernège died at the age of 77 in a retirement home in Miramont-de-Guyenne, Lot-et-Garonne on 25 November 1973.[2]

Theories

Bernège argued that household chores took up a large amount of time of a large part of the population, and thus fully justified effort to improve productivity. She analyzed household chores such as cooking, laundry, cleaning, ironing, mending, shopping, accounting, decorating, sewing, patient care, childcare and children's education, their frequency and their place in the overall domestic organization. She decomposed tasks into movements and steps, measured distances and timed each phase of each task in a typical environment.[2] She then compared these measurements to those in kitchens with functional design and modern equipment, and apartments with rational layouts designed to reduce the number of steps taken by the housewife. She found that the typical woman wasted at least two hours per day due to poor facilities, which translated into a huge loss to the French economy.[2]

Bernège thought that if housework was a job, the home should be seen as a workplace. Following Taylor, she distinguished between directing and executing tasks.[16] Unlike a factory, a housewife must perform a variety of tasks using different skills and different machines. A housewife was both worker and supervisor, the operator and the owner of machines, and their own employer.[18] Bernège told women to use "tools that simplify, mechanize and liberate," and "entrust their work to machines that will do it as well ... and much more quickly." She wrote, "Before each object in your kitchen, you should now ask the following questions: Is this the one that will save the most fuel, the most effort, the most work, the most time? And you should only be satisfied when you finally have the tool with the best output.[19]

Bernège planned an ideal utilities room where the washing appliances were placed in the sequence in which they would be used.[16] She wrote, "Work should move constantly forward, in a straight line, without coming and going or retracing steps. Study the doors, the relationship of one room to another, so that it is possible to accomplish your work in a straight line."[16] Bernège's 1950 guide to laundering Le Blanchissage domestique recommended that women with enough free space, such as rural women, should hang dirty laundry on a clothes line until there was time to wash it. To prevent rats from chewing holes, she recommended the "amusing" solution of threading a glass bottle at each end of the line. The bottle would rotate when a rat stepped on it and throw the rat down.[20]

Nowhere in Bernège's writing is there any suggestion that household management is anything but a female domain.[19] Although she was not a declared feminist, and did not question the division of household duties, Bernège called out against the "subjugation of women" and the slavery of household chores. She called on the manufactures of domestic appliances and furniture and on architects and planners to review their designs based on understanding of housework tasks.[2] Traditionally the Parisian apartment had a kitchen at the back overlooking a service yard, with food carried through a corridor to the room where the family ate.[14] Bernège called for designs that would reduce the distance between kitchen, dining room and bathroom, elevators rather than stairs, windows with large panes that could be easily cleaned rather than many small panes, surfaces that did not need to be scoured or polished, simple forms that would not accumulate dust and so on.[2]

Bernège sometimes called the person who performed the domestic task the domestic, the housewife or the working woman. She was sufficiently ambiguous for the Ligue de l’organisation ménagère to be acceptable to secular supporters of women's right to work and Catholic circles who saw adding prestige to domestic work as a revival of the historical role of the mother of the family. Business leaders saw value in women trained in Taylorized processes to fill jobs in times of labor shortage, and saw value in women being encouraged to return to their homes during the economic crisis of the 1930s.[9] In response to concerns that housewives would not have enough work to avoid boredom, Bernège replied that a woman could always find occupations. She could "improve her mind, beautify the house, cherish, direct, console, help, love."[21]

Bernège argued that the use of labor-saving devices and techniques would improve lives for families in general, and would give women a more cultivated, pleasurable existence with more time to explore fulfilling activities.[19] She was trying to define a different ideal from that of the bourgeois woman surrounded by domestic servants, but her vision of the woman performing tasks at home using factory-like methods and mechanical appliances was far from universally accepted during the period when she was most active.[22]

Publications

In 1960 it was estimated that Bernège had contributed five hundred articles and two hundred lectures in French, about ten lectures in English and twenty-five radio broadcasts. She published fourteen books and pamphlets between 1928 and 1950. La méthode ménagère was translated into German, Dutch, Italian and Polish.[23] A revised fourth edition in French was published in 1969.[3] Bernège's publications included:[1]

- Paulette Bernège (7 December 1926). Paulette Bernège, fondatrice de la Ligue d'organisation ménagère, directrice de la revue 'Mon chez moi'. Les Professions ménagères, rapport donné au Congrès, international d'orientation professionnelle féminine de Bordeaux, septembre 1926 (in French). Bordeaux: impr. J. Bière. p. 19.

- Paulette Bernège (1928). Si les femmes faisaient les maisons (in French). Paris: à Mon chez moi. p. 60.

- Paulette Bernège (28 July 1928). De la méthode ménagère (in French). Preface by Jules Hiernaux. Orléans: Tessier. p. 168.

- Paulette Bernège (11 October 1929). Les Rapports financiers entre époux, par Paulette Bernège (Extract from the Revue internationale de sociologie. Nos 7-8. Juillet-août 1929 (in French). Dives-sur-Mer (Calvados): Jean Rémy. p. 6.

- Paulette Bernège (August 1933). "Quand une femme construit sa cuisine" (PDF). L'Art Ménager: 173–175. Retrieved 2015-06-05.

- Paulette Bernège (29 May 1934). J'installe ma cuisine, par Mlle Bernège. Première partie : l'Aménagement rationnel des cuisines (in French). Lyon: Impr. du Salut public ; Éditions de la Maison heureuse. p. 61.

- Paulette Bernège (1934). De la Méthode ménagère, par Paulette Bernège (in French). Preface by Jules Hiernaux (2 ed.). Paris: Ligue de l'organisation ménagère. p. 165.

- Paulette Bernège (23 October 1934). De la méthode ménagère (in French). Preface by Jules Hiernaux. 2e édition, revue et corrigée. 5e mille. Orléans: H. Tessier. p. 165.

- Paulette Bernège (1935). Le Ménage simplifié ou la Vie en rose, par Paulette Bernège. Illustrations de Dufau (in French). Paris: libr. Stock. p. 320.

- Paulette Bernège (25 July 1936). Paulette Bernège. Le Livre de comptes de la femme économe (in French). Paris: H. Maillet ; Dunod.

- Paulette Bernège (1941). L'aluminium ménager: documentation établie à l'intention des professeurs d'économie domestique et de leurs élèves (in French). Paris: les Editions pédagogiques de l'Aluminium. p. 16.

- Paulette Bernège (1943). Paulette Bernège,... Explication (in French). Toulouse: Didier (Impr. régionale). p. 237.

- Paulette Bernège (1947). Guide d'enseignement ménager (in French). Preface by Roger Cousinet (1881-1973). Paris: la Maison rustique. p. 207.

- Paulette Bernège (1950). Paulette Bernège,... J'organise ma petite ferme (in French). Preface by André Siegfried (1875-1959). Paris: Éditions du Salon des arts ménagers. p. 112.

- Paulette Bernège (1950). Le blanchissage domestique (in French). Preface by Louis de Broglie (1892-1987) (2 ed.). Paris: Éditions du Salon des arts ménagers. p. 121.

- Paulette Bernège (1969). De la Méthode ménagère (in French). Paris: J. Lanore. p. 183.

- Paulette Bernège. Janille, paysan de la Garonne. [Paulette Bernège.] Paris aux antipodes, lettres du pays d'oc. [1ère série.] (in French). Agen: M. Delbert. p. 32.

- Paulette Bernège. Janille, paysan de la Garonne. [Paulette Bernège.] Servir la vie ou le Nouveau pacte social, lettres du pays d'oc. 2e série... (in French). Agen: M. Delbert. p. 48.

References

- Paulette Bernège (1896-1973), BnF.

- Dumont 2012.

- Bernège & Ribeill 1989, p. 59.

- Duchen 2003, p. 69.

- Henry 2003, p. 5.

- Sorisio 2002, p. 133.

- Sorisio 2002, p. 133–134.

- Clarke 2011, p. 71.

- Henry 2003, p. 9.

- Clarke 2011, p. 141.

- Badenoch 2011.

- Pulju 2011, p. 62.

- Pulju 2011, p. 63.

- Leymonerie 2006, pp. 43–56.

- Pulju 2011, p. 180.

- Duchen 2003, p. 70.

- Duchen 2003, p. 81.

- Panchasi 2009, p. 27.

- Panchasi 2009, p. 28.

- Rudolph 2015, p. 223.

- Duchen 2003, p. 91.

- Henry 2003, p. 10.

- Clarke 2011, p. 72.

Sources

- Badenoch, Alexander (2011). "Creating 'domestic science". Inventing Europe. Retrieved 2015-06-05.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bernège, Paulette; Ribeill, Georges (1989). "Le tuyau : élément essentiel de civilisation". Flux, Numéro Spécial. 5 (1): 57–74. doi:10.3406/flux.1989.910.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clarke, Jackie (2011-06-15). France in the Age of Organization: Factory, Home and Nation from the 1920s to Vichy. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-0-85745-081-4. Retrieved 2015-06-05.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Duchen, Claire (2003-09-02). Women's Rights and Women's Lives in France 1944-1968. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-98458-9. Retrieved 2015-06-05.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dumont, Marie-Jeanne (2012-12-14). "Si les femmes faisaient les maisons… », la croisade de Paulette Bernège". D-Fiction (in French). Retrieved 2015-06-05.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Henry, Odile (2003). "Femmes & taylorisme : la rationalisation du travail domestique". Agone (in French) (28). doi:10.4000/revueagone.402. Retrieved 2015-06-05.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leymonerie, Claire (2006). "Le Salon des arts ménagers dans les années 1950". Vingtième Siècle. Revue d'histoire (in French). Presses de Sciences Po (P.F.N.S.P.). 3 (91). Retrieved 2015-05-28.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Panchasi, Roxanne (2009). Future Tense: The Culture of Anticipation in France Between the Wars. Cornell University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-8014-4670-2. Retrieved 2015-06-06.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Paulette Bernège (1896-1973)". BnF. Retrieved 2015-06-05.

- Pulju, Rebecca (2011-02-14). "The Salon des arts ménagers: Learning to Consume in Postwar France". Women and Mass Consumer Society in Postwar France. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-00135-0. Retrieved 2015-05-29.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rudolph, Nicole C. (2015-03-15). At Home in Postwar France: Modern Mass Housing and the Right to Comfort. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-78238-588-2. Retrieved 2015-06-05.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sorisio, Carolyn (2002-12-01). Fleshing Out America: Race, Gender, and the Politics of the Body in American Literature, 1833-1879. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-2637-5. Retrieved 2015-06-05.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Jackie Clarke (2005). "L' organisation ménagère comme pédagogie. Paulette Bernège et la formation d'une nouvelle classe moyenne dans les années 1930 et 1940". Travail, Genre et Sociétés (in French). 1 (13): 139–157. doi:10.3917/tgs.013.0139.