Pathetic dot theory

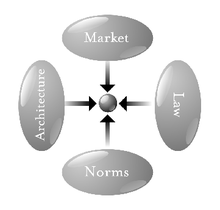

The pathetic dot theory or the New Chicago School theory was introduced by Lawrence Lessig in a 1998 article and popularized in his 1999 book, Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace. It is a socioeconomic theory of regulation. It discusses how lives of individuals (the pathetic dots in questions) are regulated by four forces: the law, social norms, the market, and architecture (technical infrastructure).

Theory

Lessig identifies four forces that constrain our actions: the law, social norms, the market, and architecture.[1] The law threatens sanction if it is not obeyed. Social norms are enforced by the community.[1] Markets through supply and demand set a price on various items or behaviors.[1] The final force is the (social) architecture.[1] By that Lessig means "features of the world, whether made, or found"; noting that facts like biology, geography, technology and others constrain our actions.[2] Together, those four forces are the totality of what constrains our action, in fashion both direct and indirect, ex post and ex ante.[1]

The theory has been formally called by Lessig in 1998 "The New Chicago School", and can be seen as a theory of regulation.[1][2]

The theory can be applied to many aspects of life (such as how smoking is regulated), but it has been popularized by Lessig's subsequent usage of it in the context of the regulation of the Internet.[1] Lessig noted that the key difference in regulation of the Internet (cyberspace), compared to regulation of the "real world" ("realspace"), is the fact that the architecture of the internet – the computer code that underlies all software – is created by humans, whereas in the real world much of the architecture, based on laws of physics, biology, and major social and cultural forces, is beyond our control.[1] Lessig sees code as an important force that should be of interest to the wider public, and not only to the programmers.[3] He notes the importance of how technology-mediated architecture, such as coded software, can affect and regulate our behavior.[4] Lessig wrote:

[The code] will present the greatest threat to both liberal and libertarian ideals, as well as their greatest promise. We can build, or architect, or code cyberspace to protect values that we believe are fundamental. Or we can build, or architect, or code cyberspace to allow those values to disappear. There is no middle ground. There is no choice that does not include some kind of building. Code is never found; it is only ever made, and only ever made by us.[5]

See also

References

- Murray, Andrew D. (January 1, 2011). "Internet regulation". In David Levi-Faur (ed.). Handbook on the Politics of Regulation. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 272–274. ISBN 978-0-85793-611-0. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- Lessig, Lawrence (June 1, 1998). "The New Chicago School". The Journal of Legal Studies. 27 (S2): 661–691. doi:10.1086/468039. JSTOR 10.1086/468039.

- Marsden, Christopher T. (2000). Regulating the Global Information Society. Routledge. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-415-24217-2. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- Korpela, Mikko; Montealegre, Ramiro; Poulymenakou, Angeliki (May 31, 2003). Organizational Information Systems in the Context of Globalization. Springer. p. 360. ISBN 978-1-4020-7488-2. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- Lessig, Lawrence (December 11, 2006). "Code Is Law / Code 2.0". Socialtext.net. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

Further reading

- Lessig, Lawrence, Code 2.0, Chapter: What Things Regulate (available in print: Lawrence Lessig (2006). Code. Lawrence Lessig. pp. 120–137. ISBN 978-0-465-03914-2. Retrieved March 14, 2013.)

- Basham, Matthew J.; Stader, David L.; Bishop, Holly N. (February 10, 2009). "How "Pathetic" is Your Hiring Process? An Application of the Lessig "Pathetic Dot" Model to Educational Hiring Practices". Community College Journal of Research and Practice. 33 (3–4): 363–385. doi:10.1080/10668920802564980.