Pat O'Leary Line

The Pat O'Leary Line, (also known as the Pat Line, the O'Leary Line, and the PAO Line) (1940-1944), was a resistance organization in France during the Second World War. The Pat O'Leary escape line helped allied soldiers and airmen stranded or shot down over occupied Europe evade capture by Nazi Germany and return to Great Britain. Downed airmen in northern France and other countries were fed, clothed, given false identity papers, hidden in attics, cellars, and people's homes, and escorted to Marseille, where the line was based. From there, a network of people then escorted them to neutral Spain. From Spain, British diplomats sent the escapees home via British-controlled Gibraltar. The Pat O'Leary Line was the oldest established escape line. Collectively, the escape lines helped about 5,000 allied military personnel escape occupied Europe. The O'Leary Line received financial assistance from MI9, a British intelligence agency.

The Pat O'Leary Line exfiltrated more that 600 allied soldiers and airmen from France to Spain. More than 100 volunteers or "helpers" as they were often called, mostly French, working for the O'Leary Line were arrested and imprisoned by Vichy French or German authorities. Most were imprisoned for the remainder of the war and some were executed or died in concentration camps.[1]

Overview

The Pat O'Leary Line was one of several escape and evasion networks in the Netherlands, Belgium, and France during World War II. Along with networks such as the Comet Line, the Shelburne Escape Line, and others, they are credited with aiding about 5,000 Allied airmen and soldiers, about one-half British and one-half American, escape occupied Nazi-occupied Europe during World War II. Approximately 12,000 people, nearly all civilians and almost one-half women, were engaged in the work of the escape lines. About 500 of them were arrested and executed or died in concentration camps. Many more were imprisoned by the Germans.[2][3]

In the words of a member of the escape lines, "it was raining aviators" over Europe at the height of World War II. For example, on one day, October 14, 1943, 82 bombers with 800 crewmen of the U.S. Eighth Air Force were shot down or crash-landed in occupied Europe. Most of the crewmen were killed or captured, but some were rescued by escape lines and made it back to Great Britain. "The morale of airmen on bases rose considerably when they saw their buddies miraculously reappear after having been shot down over occupied Europe."[4]

History

The Dunkirk evacuation of France by British forces in June 1940 left thousands of British and Allied soldiers stranded on the European mainland. Most surrendered or were captured by the Germans, but a few made their way to Vichy France, nominally independent, especially the coastal city of Marseille. From July to October 1940, working for the British intelligence agency MI9, an Armenian, Nubar Gulbenkian, laid the groundwork for a network of people to guide stranded allied soldiers over the Pyrenees mountains to neutral Spain from where they could be repatriated to the United Kingdom. As the war went on most of the escapees became airmen shot down over occupied Europe. [5]

The initial leader of what became known as the Pat O'Leary Line was a Scottish soldier, Ian Garrow. Taking advantage of the limited freedom of movement initially accorded him by the Vichy government, he organized the escape system, recruited dozens--and later hundreds--of volunteer workers for the escape line, and found funds for the expenses of housing, transporting, and documenting the allied soldiers and airmen. At first, some of the exfiltrations to Spain were by sea, but the more common route was for local guides (often smugglers familiar with the Pyrenees), to accompany the soldiers and airmen on foot across the border to Spain. They escapees were then moved onward by train or car to the British Consulate in Barcelona, and then flown back to the United Kingdom, usually from Gibraltar. Garrow gathered funds for the expenses of the escape line from residents of Marseille, but MI9 later financed the costs.[6][7] Working for the escape line became more dangerous in November 1942 when the German military occupied Vichy France and took control of much of the government.[8]

Garrow was arrested and imprisoned by Vichy French police in October 1941. His successor was Albert-Marie Guérisse, a medical officer in the Belgian army. After Belgium's surrender to the Germans in 1940, Guérisse became a British intelligence operative. He adopted the code name "Pat O'Leary," thus the name of the escape line.[10]. Guérisse was arrested by the Gestapo on March 2, 1943, betrayed by Roger le Neveu who had worked with the O'Leary line but had been bribed or blackmailed to work for the Germans. The arrest of Guérisse and many others nearly destroyed the O'Leary Line, but a 61-year-old woman named Marie Dissard (code named "Françoise) revived the Line in summer 1943. Dissard lived in Toulouse and sheltered many downed airmen in her apartment and escorted them or directed their escort to Spain. Airey Neave, the M19 agent who supported the Pat O'Leary line, said that the eccentric Dissard and her cat were "almost the sole survivors" of the O'Leary Line. Under the leadership of Dissard, the remnants of the O'Leary Line are often called the "Françoise Line."[11][12]

Routes

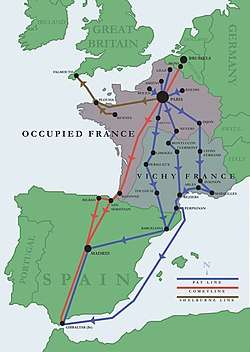

The O'Leary Line collected allied soldiers and, after 1940, mostly airmen from northern France, plus a few from other countries. The military personnel were passed down from safe house to safe house and escort-to-escort to Marseille. Initially, many were exfiltrated by felucca down the French and Spanish coasts to Gibraltar. Later, as security tightened, the Line used land routes through the easternmost Pyrenees, and, as that became more hazardous, shifted its main routes to the high Pyrenees further west which were not patrolled extensively by German soldiers, French police, and Spanish border guards. With the arrest of many O'Leary Line workers and leaders in Marseille, the primary collection point for escapees in 1943 and 1944 became Toulouse.[13]

The most famous of the routes is known as the "Freedom Line," ("Chemin de la Liberté"). From Toulouse, the airmen were taken to the town of Saint-Girons at the foot of the Pyrenees. From there the guide and escapees hiked across the border, via the slopes of Mont Valier, 2,838 metres (9,311 ft) in elevation, and onward to the small town of Esterri d'Aneu in Spain. The distance from Saint-Girons to Esterri d'Aneu was only 42 kilometres (26 mi) in straight line distance, but it involved several days of climbing steep slopes, often through snow and ice.[14]

Betrayals

Given the large number of helpers involved in escape lines, their isolation from each other, and their geographic dispersion, the escape lines were relatively easy to infiltrate by German agents. The O'Leary line was nearly destroyed by two betrayers: Harold Cole, code name "Paul," and Roger Le Neveu, called "Roger Le Legionnaire." Cole worked his way into the confidence of the O'Leary line by successfully escorting several groups of airmen from Lille in northernmost France to Marseille. The former English soldier was captured by the Germans in December 1941, and gave the Germans information who led to the arrest of several dozen helpers working for the O'Leary Line, nearly destroying the Line in northern France.[15] Neveu, a Frenchman, similarly worked his way into the confidence of the O'Leary Line and was responsible for the arrest of Albert-Marie Guérisse and other O'Leary line helpers in Marseille in March 1943. The O'Leary Line was reconstituted in Toulouse where it functioned for the remainder of the war.[16]

Other notable members of the Line

Important helpers of the Pat O'Leary Line in Marseille were George Rodocanachi, a medical doctor, Donald Caskie, a pastor in charge of the British Seaman's Mission, and Louis Nouveau, a businessman, and his wife, Renée.[17] All three men were arrested and spent the rest of the war in prison. Rodocanachi died in the Buchenwald concentration camp. Renée Nouveau escaped to Great Britain.[18][19] Nancy Wake was a courier for the O'Leary Line and, along with her husband, Henri Fiocca, sheltered many airmen in her luxurious Marseille apartment. Wake escaped to Spain in 1943; the Gestapo arrested and executed Fiocca.[20] Andrée Borrel evaded arrest and became an agent of the United Kingdom's clandestine organization, the Special Operations Executive, and was later captured and executed.[21]Mary Lindell, resident in Paris, collected downed airmen and sent them to the O'Leary Line in Marseille. She founded the "Marie-Claire Line" and was imprisoned by the Germans.[22]

References

- Neave, Airey (1970), The Escape Room, New York: Doubleday, pp. xiii, 121

- Hemingway-Douglass, Reanne (2014), "The Shelburne Escape Line," Anacortes, Washington: Cave Art Press, pp. 1-2

- Neave, pp. xii-xiii

- Ottis, Sherrie, Sherri Green (2001), Silent Heroes, Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, p. 25

- Neave, pp. 63-65

- Neave, pp. 64-67

- Ottis, pp. 76-80

- "This Day in History: November 10, 1942," , accessed 26 Oct 2019

- Long, Christopher, "Dr. George Rodocanachi," , accessed 23 Oct 2019

- Neave, pp. 66-67

- Neave, pp. 116-121

- "The Pat O'Leary (or PAO) Line," , accessed 28 Oct 2019

- "The Pat O'Leary Line," WW2 Escape Lines Memorial Society, , accessed 29 Oct 2019

- Goodall, Scott, "The Freedom Trail (chemin de la liberté): WWII escape route to Spain," , accessed 29 Oct 2019

- Ottis, pp. 93-96

- Ottis, pp. 112-117

- Ottis, pp. 80-84

- Ottis, pp. 80-84, 165-166

- Long, Christopher, "Dr. George Rodocanachi," , accessed 23 Oct 2019

- "Nancy Wake, Proud Spy and Nazi Foe, Dies at 98," The New York Times, , accessed 27 Oct 2019

- O'Connor, Bernard (2012), Churchill's Angels, Stroud, Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing, p. 55

- "The Marie Clair Line," , accessed 17 Oct 2019