Parivrajaka dynasty

The Parivrajaka (IAST: Parivrājaka) dynasty ruled parts of central India during 5th and 6th centuries. The kings of this dynasty bore the title Maharaja, and probably ruled as feudatories of the Gupta Empire. The dynasty is known from inscriptions of two of its kings: Hastin and Samkshobha.

Parivrajaka | |

|---|---|

| c. 5th century CE–c. 6th century CE | |

| Status | Vassal of Gupta Empire |

| Capital | Unknown |

| Government | Monarchy |

| History | |

• Established | c. 5th century CE |

• Disestablished | c. 6th century CE |

Political status

The Parivrajaka inscriptions refer to the imperial Gupta dynasty, but do not mention any Gupta overlord. However, the use of title "Maharaja" (generally used by feudatory kings) suggests that they were vassals of the Guptas.[1] In addition, the Parivrajaka inscriptions state that the dynasty ruled the forest kingdoms; the Allahabad pillar inscription of the Gupta emperor Samudragupta states that he subjugated all the forest kingdoms.[2]

When the Gupta empire started declining, they acknowledged nominal Gupta suzerainty.[1]

Multiple inscriptions of the dynasty mention a year of an uncertain calendar era, with the term "Gupta-nṛipa-rājya bhuktau", which has been translated variously by different scholars:

- According to Moirangthem Pramod, the Parivrajakas were reduced to the governors of a bhukti (province) after the Gupta conquest.[1]

- According to P. L. Gupta, the Parivrajakas were originally vassals of the Gupta, but became independent by the time of Hastin. Even after becoming independent, they continued to use the Gupta era, which is what the term refers to.[3]

- According to H. H. Wilson, the term refers to the occupation of the Parivrajaka kingdom by the Guptas, and the calendar era starts from this date of occupation.[3]

- According to Dr. Hall, the term refers to end of the Gupta sovereignty, and the calendar era starts from beginning of the post-Gupta period.[3]

History

The term "Parivrajaka" literally means a wandering ascetic. The family came from a lineage of Brahmins of Bharadvaja gotra, who may have been wandering ascetics some time in the past.[4] Another possibility is that the term "Parivrajaka" is a reference to the practice of kings abdicating their thrones in old age and becoming wandering ascetics, in accordance with the ashrama system.[3]

Early rulers

The earliest known member of the dynasty is Susharman, who is known only from the Khoh inscription of Samkshobha. The inscription describes Susharman as a learned ascetic from Bharadvaja gotra, and compares him to the legendary sage Kapila. It states that he knew "the whole truth" and fourteen branches of science.[5]

Maharaja Devadhya was a descendant of Susharman, and was succeeded by his son Maharaja Prabhanjana. Prabhanjana was succeeded by his son Maharaja Damodara.[6]

Maharaja Hastin

Maharaja Hastin, the son of Damodara, is credited with several military victories, although the inscriptions do not mention any of his adversaries. According to K. C. Jain, these claims probably refer to his participation in Guptas' war against the Hunas. He was a charitable king, and donated cows, horses, elephants, gold and land to Brahmins.[1]

According to the Khoh inscription of his son Samkshobha, Hastin ruled the kingdom of ābhala (or āhala; later Dahala) and the 18 aavi-rājya ("forest kingdoms"). The identity of these 18 forest kingdoms is not certain, but they were most probably in the Vindhyan region.[9]

Hastin ruled for at least 42 years, as his earliest extant inscription is dated to the year 156, and his last inscription is dated to the year 198. Assuming these years to be in the Gupta era, Hastin would have been a contemporary of the Gupta kings Budhagupta, Vainyagupta, Bhanugupta and possibly Narasimhagupta. Budhagupta was a relatively strong ruler among these, and Hastin appears to have been his vassal. This theory is corroborated by the discovery of a copper-plate inscription issued during Budhagupta's reign from Sankarapur in Sidhi district.[9]

Hastin was a Shaivite, as suggested by his Bhumara inscription, which describes him as meditating at the feet of Mahadeva (Shiva).[9]

Some ancient silver coins bearing the legend "Raa Hastin" have been discovered. Historians such as E. J. Rapson, R. D. Banerji and B. P. Sinha identified him with Hastin on palaeographic basis. However, Dasharatha Sharma and P. L. Gupta identify him with the Pratihara king Vatsaraja who held the title "Rana Hastin" according to the Kuvalayamāla of Udyyotana Suri. According to Gupta, these coins cannot be dated before the 8th century CE. This theory is corroborated by the fact that no Gupta vassals issued coins in their own names.[9]

Maharaja Samkshobha

Maharaja Samkshobha (or Sakshobha) succeeded his father Hastin, and inherited the entire ancestral territory, including the 18 kingdoms. Like his father, he also made land grants for religious merit. He maintained the orthodox varna and ashrama systems.[10]

Unlike his father who invoked Shiva, Samkshobha's Khoh inscription opens with an invocation to the god Vasudeva. He is the last known of the dynasty, which probably ended with him. The end of the Parivrajaka rule probably coincided with the end of the Gupta rule, which was followed by the Aulikara rule in central India.[10]

Genealogy

The following members of the dynasty are known (IAST names in brackets):[11]

- Susharman (Suśarman)

- Devadhya (Devāḍhya)

- Prabhanjana (Prabhañjana)

- Damodara (Dāmodara)

- Hastin, r. c. 475–517 CE

- Samkshobha or Sakshobha (Saṃkṣobha), r. c. 518–528 CE

Inscriptions

The following inscriptions from the Parivrajaka reign have been discovered. All are copper-plate inscriptions, except the Bhumara stone pillar inscription:[11]

| Find spot | Issued by | Year (CE year, assuming Gupta era)[12] | Objective | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khoh | Maharaja Hastin | 156 (475 CE) | Grant of the Vasuntarashaika village by Maharaja Hastin to Gopasvamin and other Brahmins | [13] |

| Khoh | Maharaja Hastin | 163 (482 CE) | Grant of the Korparika agrahara by Maharaja Hastin to Brahmins | [14] |

| Jabalpur | Maharaja Hastin | 163 (482 CE) | Grant of a village by Maharaja Hastin to Brahmins, in Gupta year 170 | [14] |

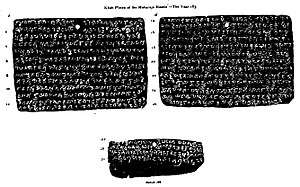

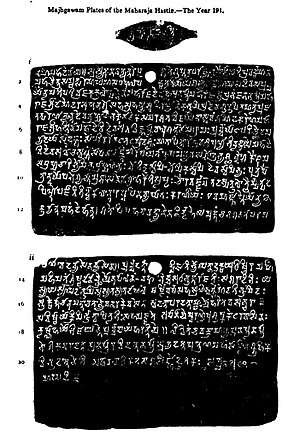

| Majhgawan | Maharaja Hastin | 191 (510 CE) | Grant by Maharaja Hastin at the request of Mahadevi-deva | [14] |

| Navagrama | Maharaja Hastin and Uchchhakalpa Maharaja Sharvanatha | 198 (517 CE) | Grant of a village by Maharaja Hastin to Brahmins of Parashara gotra and Madhyandina Shakha | [14] |

| Bhumara (or Bhummra) | Maharaja Hastin | D. C. Sircar suggests that this is a family stone. The inscription mentions Ambalode village, which according to John Faithfull Fleet, was located at the Parivrajaka–Uchchhakalpa border | [15] | |

| Betul | Maharaja Sakshobha (Samkshobha) | 199 (518 CE) | Grant of the Prastaravataka village and Dvāravāika quarter in Tripuri province, by Maharaja Hastin to Bhanusvamin (a Brahmin of Bharadvaja gotra) | [4] |

| Khoh | Maharaja Samkshobha | 209 (528 CE) | Grant of the Opani village by Maharaja Hastin to a temple of goddess Pishapuri, at the request of Chhodugomin. Pishapuri was probably a local form of Lakshmi. | [4] |

References

- Moirangthem Pramod 2013, p. 95.

- Moirangthem Pramod 2013, p. 91.

- Moirangthem Pramod 2013, p. 94.

- Moirangthem Pramod 2013, p. 93.

- Moirangthem Pramod 2013, p. 935.

- Ashvini Agrawal 1989, p. 259.

- Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum Vol 3 p.102ff

- Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum Vol 3 p.108ff

- Moirangthem Pramod 2013, p. 96.

- Moirangthem Pramod 2013, p. 97.

- Moirangthem Pramod 2013, pp. 91–93.

- D. C. Sircar 1996, p. 156.

- Moirangthem Pramod 2013, pp. 91–92.

- Moirangthem Pramod 2013, p. 92.

- Moirangthem Pramod 2013, pp. 92–93.

Bibliography

- Ashvini Agrawal (1989). Rise and Fall of the Imperial Guptas. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0592-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- D. C. Sircar (1996). Studies in the Political and Administrative Systems in Ancient and Medieval India. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 9788120812505.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moirangthem Pramod (2013). "The Parivrajaka Maharaja" (PDF). Asian Journal of Multidimensional Research. 2 (4). ISSN 2278-4853.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Siddham – the South Asia Inscriptions Database: Hastin and Samkshobha

- Parivrаjaka inscriptions by D.N Lielukhine, Oriental Institute