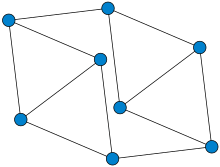

Parity graph

In graph theory, a parity graph is a graph in which every two induced paths between the same two vertices have the same parity: either both paths have odd length, or both have even length.[1] This class of graphs was named and first studied by Burlet & Uhry (1984).[2]

Related classes of graphs

Parity graphs include the distance-hereditary graphs, in which every two induced paths between the same two vertices have the same length. They also include the bipartite graphs, which may be characterized analogously as the graphs in which every two paths (not necessarily induced paths) between the same two vertices have the same parity, and the line perfect graphs, a generalization of the bipartite graphs. Every parity graph is a Meyniel graph, a graph in which every odd cycle of length five or more has two chords. For, in a parity graph, any long odd cycle can be partitioned into two paths of different parities, neither of which is a single edge, and at least one chord is needed to prevent these from both being induced paths. Then, partitioning the cycle into two paths between the endpoints of this first chord, a second chord is needed to prevent the two paths of this second partition from being induced. Because Meyniel graphs are perfect graphs, parity graphs are also perfect.[1] They are exactly the graphs whose Cartesian product with a single edge remains perfect.[3]

Algorithms

A graph is a parity graph if and only if every component of its split decomposition is either a complete graph or a bipartite graph. Based on this characterization, it is possible to test whether a given graph is a parity graph in linear time. The same characterization also leads to generalizations of some graph optimization algorithms from bipartite graphs to parity graphs. For instance, using the split decomposition, it is possible to find the weighted maximum independent set of a parity graph in polynomial time.[4]

References

- Parity graphs, Information System on Graph Classes and their Inclusions, retrieved 2016-09-25.

- Burlet, M.; Uhry, J.-P. (1984), "Parity graphs", Topics on perfect graphs, North-Holland Math. Stud., 88, North-Holland, Amsterdam, pp. 253–277, doi:10.1016/S0304-0208(08)72939-6, MR 0778766.

- Jansen, Klaus (1998), "A new characterization for parity graphs and a coloring problem with costs", LATIN'98: theoretical informatics (Campinas, 1998), Lecture Notes in Comput. Sci., 1380, Springer, Berlin, pp. 249–260, doi:10.1007/BFb0054326, hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0014-7BE2-3, MR 1635464.

- Cicerone, Serafino; Di Stefano, Gabriele (1997), "On the equivalence in complexity among basic problems on bipartite and parity graphs", Algorithms and computation (Singapore, 1997), Lecture Notes in Comput. Sci., 1350, Springer, Berlin, pp. 354–363, doi:10.1007/3-540-63890-3_38, MR 1651043.