Pari Khan Khanum

Pari Khan Khanum (Persian: پریخان خانم, also spelled Parikhan Khanum; 1548–12 February 1578, aged 29) was a Safavid princess, the daughter of the Safavid king (shah) Tahmasp I (r. 1524 – 1576) and his Circassian consort, Sultan-Agha Khanum. An influential figure in the Safavid state, Pari Khan Khanum was well educated and knowledgeable in traditional Islamic sciences such as jurisprudence, and was an accomplished poet.

| Pari Khan Khanum پریخان خانم | |

|---|---|

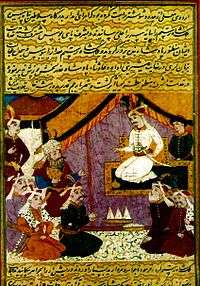

.jpg) Painting of a seated princess, most likely Pari Khan Khanum[1] | |

| Born | August 1548 Ahar, Iran |

| Died | 12 February 1578 (aged 29) Qazvin, Iran |

| Spouse | Badi-al Zaman Mirza Safavi |

| Dynasty | Safavid |

| Father | Tahmasp I |

| Mother | Sultan-Agha Khanum |

| Religion | Shia Islam |

She played a crucial role in securing the succession of her brother Ismail II (r. 1576–1577) to the Safavid throne. During Ismail's brief reign, her influence lessened, but then increased during the reign of Ismail's successor, Mohammad Khodabanda (r. 1578–1587), even becoming the de facto ruler of the Safavid state for a short period. She was strangled to death on 12 February 1578 at Qazvin because her influence and power were perceived as dangerous by the Qizilbash.

Biography

Youth

Pari Khan Khanum was born as the second daughter of the Safavid shah Tahmasp I by his Circassian wife Sultan-Agha Khanum in August 1548 at Ahar.[2] When his brother Bahram Mirza Safavi died in 1549, Tahmasp took care of his children, even proclaiming prince Badi-al Zaman Mirza Safavi his own son. He appointed him as the governor of Sistan in 1557, and offered him Pari Khan Khanum (who was at that time 10 years old) as a wife, which he accepted. However, since she was Tahmasp's favored daughter, she was not allowed to go alongside her husband to Sistan.[2]

Historians including Shoreh Gholsorki, author of a 1995 study of Pari Khan Khanum, believe that she was only engaged to Badi al-Zaman and that no marriage took place, since Pari Khan Khanum chose a bureaucratic life in the capital alongside her father over married life in Sistan.[3]

Succession disputes

Pari Khan Khanum's participation in the affairs of the Safavid state started during the last years of Tahmasp's reign. Disenchanted with the bureaucratic life, her father granted her the authority and legal status that provided the basis for her later rise to power.[4]

On 18 October 1574 Tahmasp became ill and twice came close to dying without having chosen a successor. Pari Khan Khanum took care of him during his illness, bringing them even closer.[5] Simultaneously, the main chieftains of the Qizilbash arranged a meeting to discuss who should be the successor. The Ustalju clan and the Shaykhavand clan (which was related to the Safavid family) favored Tahmasp's son Haydar Mirza Safavi. The Georgians also supported him since his mother was Georgian.

The Rumlu, Afshar, and the Qajar clan favored Ismail Mirza Safavi, Haydar's older brother, who was jailed in the Qahqaheh Castle. Pari Khan Khanum also favored Ismail Mirza, and she had the support of the Circassians.[2][6] During Tahmasp's illness, supporters of Haydar Mirza sent a message to the Khalifa Ansar Qaradghlu, castellan of Qahqaheh Castle, and requested that he have Ismail Mirza killed. However, Pari Khan Khanum uncovered the plot and told Tahmasp about it. Tahmasp, who still had some feelings for Ismail Mirza due to the latter's courage during the encounters with the Ottoman Empire, sent a group of Afshar musketeers to the Qahqaheh Castle to safeguard him.[2] Two months later, Tahmasp recovered from his illness; he died two years later, on 14 May 1576, in Qazvin. Haydar Mirza was the only son who was with Tahmasp when he died. The following day, he announced himself as the new shah. Normally, some Qizilbash men would guard the royal palace and take turns serving guard with other others. Unfortunately for Haydar Mirza, on that day all the Qizilbash guards were from the Rumlu, Afshar, Qajar, Bayat, or the Dorsaq tribes – all loyal supporters of Ismail Mirza.[2]

When Haydar Mirza realized the danger of his unprotected position, he took Pari Khan Khanum (who was also in the palace) as a hostage.[2] Pari Khan Khanum then "threw herself at her brother's feet in the presence of Haydar Mirza's mother", and tried to urge him to let her leave the palace, stating that she was the first to acknowledge his rule by prostrating herself before him: she vowed that she would attempt to persuade Ismail Mirza's supporters (including her full brother Suleiman Mirza and her Circassian uncle Shamkhal Sultan) to change their mind. Haydar Mirza accepted her request, and gave her permission to leave the palace, but she broke her oath and gave Shamkhal Sultan the keys to the palace gate.[2]

Haydar Mirza's supporters hurried to his palace to save him, but the palace guards, who disliked Haydar Mirza even after he had tried to win them to his side by declaring several assurances, closed the gates,[2] while Ismail Mirza's supporters entered the palace and went to its inner part. Haydar Mirza's supporters managed to break through the gate, but did not reach there in time – Ismail Mirza's supporters discovered Haydar Mirza, dressed as a woman in the royal harem, and beheaded him.[7] His bloody head was then thrown down to Haydar Mirza's supporters, who gave in and thus allowed Ismail Mirza to ascend the throne as Ismail II.[2]

De facto ruler of the Safavid realm

Under Ismail II

During the dynastic struggle between Haydar Mirza and Ismail Mirza, Pari Khan Khanum became the de facto ruler of the state;[2] it was she who ordered all the princes and top-ranking members of the realm to gather at Qazvin's main mosque on 23 May 1576, where cleric Mir Makhdum Sharifi Shirazi read the khotbeh in the name of Ismail Mirza, confirming him as the new shah of the Safavid dynasty.[2]

Ismail Mirza, who was still in the Qahqaheh Castle, was soon escorted out of the place with thousands of Qizilbash warriors, reaching the outskirts of Qazvin on 4 June 1576. In the course of the 31 days following the death of Tahmasp, the henchmen and chieftains of the Qizilbash clans had visited the palace of Pari Khan Khanum every day and, according to Iskandar Beg Munshi, "informed her of the urgent business of the realm be it fiscal or financial or to do with politics of the day and nobody had any inclination or dared to disobey her command".[2]

After entering Qazvin, Ismail Mirza did not advance to the regal palace directly since the astrologists had stated that the time was ominous. He thus stayed for 14 days at the house of Husaynquli Khulafa, the leader of the Rumlu clan and the Khalifat al-Khulafa (administrator of Sufi affairs). Although Ismail Mirza held the title of shah, the majority of the Qizilbash officers and high-ranking statesmen continued to visit Pari Khan Khanum's palace. At the same time, Pari Khan Khanum had managed to organize a remarkable court for herself "where her attendants and ladies-in-waiting acted as if they were serving at a proper royal court".[2]

Ismail Mirza ascended to the crown under the dynastic name of Ismail II on 22 August 1576.[8] His 19 years of imprisonment in the Qahqaheh castle had greatly affected him, and he was not inclined to allow displays of authority by any other individual. He announced that it was prohibited for Qizilbash chieftains, officers, and high-ranking officials to enter Pari Khan Khanum's palace. He dissolved the duties of her wardens and her court servants and seized an extensive collection of properties belonging to her. Moreover, he displayed a cold and non-approachable behaviour towards her when he allowed her an audience.[2]

Ismail II's lack of gratitude toward Pari Khan Khanum, who had fought so hard to make him shah of the Safavid dynasty, made her feel hostile towards him, and motivated her to exact vengeance. On 25 November 1577 Ismail II died abruptly and without any initial signs of bad health. The court doctors, who checked the corpse, surmised that he may have died from poison. The general agreement was that Pari Khan Khanum had resolved to have him poisoned with the help of the mistresses of the inner harem in retaliation for his bad behaviour towards her.[2] With Ismail II out of the way, Pari Khan Khanum regained her authority and control. State grandees, clan chieftains, officers, and officials carried out the orders delivered by her deputies and served according to her word.[2]

Alarmed that the announcement of Ismail II's death would start discontent in the capital, the aristocracy kept the doors of the palace locked until a decision was reached regarding the succession. According to some accounts, after Ismail II's death a group of statesmen asked Pari Khan Khanum to succeed her brother, which offer she apparently declined.[9]

In order to clear up the succession crisis, the Qizilbash chieftains agreed to appoint the future shah after consulting with each other and then notifying Pari Khan Khanum of their choice. At first they discussed the resolution that Shoja al-Din Mohammad Safavi, the eight-month-old infant son of Ismail II, should be crowned as shah while in reality state affairs would be taken care of by Pari Khan Khanum. This suggestion, however, did not obtain the approval of most of the assembly since it would have swayed the balance of power among many Qizilbash clans. Ultimately the assembly agreed to appoint Mohammad Khodabanda, the elder brother of Ismail II, as shah.[2]

Under Mohammad Khodabanda

The appointment of Mohammad Khodabanda was supported and approved by Pari Khan Khanum, due to him being a pleasure-seeking, nearly blind man of old age. Since he was the approved successor, Pari Khan Khanum could take advantage of his weakness and rule herself. She made an agreement with the Qizilbash chieftains that Mohammad Khodabanda would remain shah in name, while she and her envoys would continue directing the interests of the state.[2]

When Mohammad Khodabanda was crowned shah, the Safavid aristocracy, officers, and provincial governors wanted approval from Pari Khan Khanum to give him a congratulating visit. Pari Khan Khanum's sphere of influence and authority was so enormous that no one had the courage to visit Shiraz without her unambiguous approval.[2] From the day Mohammad Khobanda was appointed shah, his wife Khayr al-Nisa Begum, who was better known by her title of Mahd-e Olya, took control of his affairs. She was aware of her husband's deficiencies, and to make up for his lack of uprightness and quality she resolved to try to become the practical ruler of the Safavid state.[2]

Mohammad Khodabanda and Mahd-e Olya entered the environs of Qazvin on 12 February 1578. This brought an end to the indisputable rule that Pari Khan Khanum had enjoyed for two months and 20 days. Although she was still the practical ruler of the state, she would now meet opposition from Mahd-e Olya and her allies. When they reached the city, Pari Khan Khanum gladly received them with great grandeur and a parade, sitting in a golden-spun litter, while being guarded by 4,000–5,000 private guards, inner-harem personal assistants, and court attendants.[2]

Death

Mahd-e Olya was informed by the welcoming social gatherings in Qazvin of the great influence and power held by Pari Khan Khanum, thus confirming what she had already been told by Mirza Salman Jaberi, the former grand vizier of Ismail II. She then realized that as long as Pari Khan Khanum was alive, she would not be able to dominate the interests of the Safavid state and become the de facto ruler of the country. She thus began planning to have her killed.[2]

The order was executed in 12 February 1578, when Khalil Khan Afshar, who had served as Pari Khan Khanum's tutor during the reign of Tahmasp. While Pari Khan Khanum was en route to her home with her servants, Khalil Khan Afshar appeared with his men and a fight ensued. Pari Khan Khanum was eventually seized and taken to his home, where he had her strangled to death.[10][2] Her uncle, Shamkhal Sultan, was executed shortly afterward, and Ismail II's son Shoja al-Din Mohammad Safavi was murdered.[11]

References

- Soudavar 2000, pp. 60, 68.

- Parsadust 2009.

- Gholsorkhi 1995, p. 146.

- Gholsorkhi 1995, p. 156.

- Gholsorkhi 1995, p. 147.

- Nashat & Beck 2003, p. 153.

- Blow 2009, p. 20.

- Savory 2007, p. 69.

- Gholsorkhi 1995, p. 153.

- Gholsorkhi 1995, p. 155.

- Savory 2007, p. 71.

Sources

- Matthee, Rudi (2011). Persia in Crisis: Safavid Decline and the Fall of Isfahan. I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–371. ISBN 0-85773-181-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Babaie, Sussan (2004). Slaves of the Shah: New Elites of Safavid Iran. I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–218. ISBN 978-1-86064-721-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Newman, Andrew J. (2008). Safavid Iran: Rebirth of a Persian Empire. I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–281. ISBN 978-0-85771-661-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Savory, Roger (2007). Iran under the Safavids. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–288. ISBN 0-521-04251-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Roemer, H.R. (1986). "The Safavid period". The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 5: The Timurid and Safavid periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 189–351. ISBN 978-0-521-20094-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Parsadust, Manuchehr (2009). "PARIḴĀN ḴĀNOM". Encyclopaedia Iranica.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nashat, Guity; Beck, Lois (2003). Women in Iran from the Rise of Islam to 1800. University of Illinois Press. pp. 1–253. ISBN 978-0-252-07121-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Daryaee, Touraj (2012). The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–432. ISBN 0-19-987575-8. Archived from the original on 2019-01-01. Retrieved 2015-07-30.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Blow, David (2009). Shah Abbas: The Ruthless King Who became an Iranian Legend. London, UK: I. B. Tauris & Co. Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84511-989-8. LCCN 2009464064.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mitchell, Colin P. (2009). The Practice of Politics in Safavid Iran: Power, Religion and Rhetoric. I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–304. ISBN 0-85771-588-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gholsorkhi, Shohreh (1995). Pari Khan Khanum: A Masterful Safavid Princess. Iranian Studies, vol. 28, no. 3/4. pp. 143–156. ISBN 0-85773-181-5. JSTOR 4310940.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Soudavar, Abolala (2000). "The Age of Muhammadi". Muqarnas. 17: 53–72. doi:10.2307/1523290.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)