Paper sons

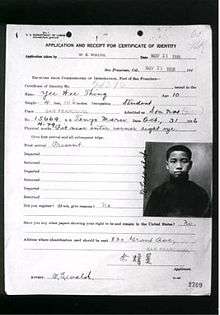

Paper sons or paper daughters is a term used to refer to Chinese people that were born in China who illegally immigrated to the United States by purchasing fraudulent documentation which stated that they were blood relatives to Chinese Americans who had already received U.S. citizenship. Typically it would be relation by being a son or a daughter.[1] Many fled China because of war and poverty. Several historical events such as the Chinese Exclusion Act and San Francisco earthquake of 1906 caused the illegal documents to be produced.[2]

Background

With the Chinese Exclusion Act enacted in 1882, Chinese people were excluded from entering the United States from China unless they were of elite status. It was the only law in American history to deny naturalization in or entry into the United States based upon a specific ethnicity or country of birth, though it was not the only law to deny citizenship based on ethnicity or country of birth (as Native- and African-American, among other Non-White American, people had at various times been denied citizenship based upon ethnicity; and not every American who was born overseas to at least one American parent was granted by-birth citizenship until the passage of the 1952 Immigration and Naturalization Act). It stated that the coming of Chinese laborers would endanger the order of localities.[2] As the American economy plummeted, problems of unemployment arose and blame was placed upon the Chinese for taking over jobs for low pay. In 1892, this act was renewed for another ten years in the form of the Geary Act. It was eventually made permanent in 1902.[3]

—Duncan E. McKinlay, Assistant U.S. District Attorney, speaking at the 1901 Chinese Exclusion Convention[4]

In 1906, the San Francisco earthquake caused a huge fire that destroyed public birth documents. Suddenly a new opportunity for citizenship arose: Chinese men who were already in the United States could claim that they were born in the United States. Other Chinese men would travel back to China as United States citizens and report that their wives had given birth to a son. Consequently, this made the child eligible to be a United States citizen, for which they would receive a document. These documents could then be used for their actual sons, or sold to friends, neighbors, and strangers.[5] This was termed as a "slot" and would then be available for purchase to men who had no blood relationships in the United States in order to be eligible to enter the United States. Merchant brokers often acted as middlemen to handle the sale of slots.[6]

To truly enforce the Chinese Exclusion Act, an Immigration Station located in Angel Island in 1910, questioned and interrogated immigrants coming from 84 different countries with the majority of immigrants being Asian and Chinese, being the largest ethnic group at the time of establishment. Since official records were often non-existent, an interrogation process was created to determine if the immigrants were related as they had claimed. On average an interrogation process could take up to 2 – 3 weeks, but some immigrants were interrogated for months. Questions could include details of the immigrant's home and village as well as specific knowledge of his or her ancestors.[7] These questions had been anticipated and thus, irrespective of the true nature of the relationship to their sponsor, the applicant had prepared months in advance by committing these details to memory. Their witnesses — usually other family members living in the United States — would be called forward to corroborate these answers. Any deviation from the testimony would prolong questioning or throw the entire case into doubt and put the applicant at risk of deportation, and possibly everyone else in the family connected to the applicant as well. A detention center was in operation for thirty years; however, there were many concerns about the sanitation and safety of the immigrants at Angel Island, which proved to be true in 1940 when the administration building burned down. As a result, all the immigrants were relocated to another facility. The Chinese Exclusion Act was eventually repealed in 1943.[8]

After the Chinese Exclusion Act

After China became a World War II ally, that vast power over non-citizens was deployed in raids against immigrants of various ethnic groups whose politics were considered suspect. Many paper sons suddenly faced the exposure of their fraudulent documentations. The United States government was tipped off by an informer in Hong Kong as part of a cold war effort to stop illegal immigration. Many Paper Sons were scared of being deported back to China.[9] Only in the 1960s did new legislation broaden immigration from Asia and gave paper sons a chance to tell the truth about who they were and restore their real names in "confessional" programs. But many chose to stick with their adopted names for fear of retribution and took their true names to their graves. Many Paper sons never told their descendants about their past; leaving them with confusion and disconnecting them from their family history. Some paper sons even went as far as adopting the American lifestyle by not teaching their children their home dialects and forgetting any Chinese cultural aspects such as their cultural foods and rituals.[10]

See also

References

- "My Father Was a Paper Son". Archived from the original on 2015-09-06.

- ""Paper Sons": Chinese American illegal immigrants". Youtube. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- "Chinese Exclusion Act (1882)". Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- McKinlay, Duncan E. (23 November 1901). "Legal Aspects of the Chinese Question". San Francisco Call. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- See, Lisa. "'Paper sons,' hidden pasts". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- Chin, Thomas. "Paper Sons". Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- "United States Immigration Station (USIS)". Angel Island Conservancy. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- "ife on Angel Island". Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- BERNSTEIN, NINA. "Immigration Stories, From Shadows to Spotlight". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- Ni, Ching-Ching (24 January 2010). "A Chinese American immigration secret emerges from the dark days of discrimination". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 6 November 2015.