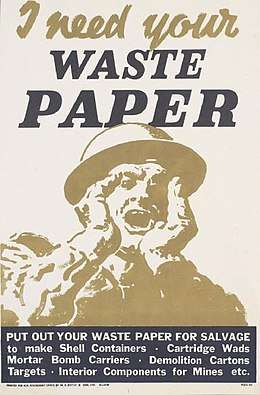

Paper Salvage 1939–50

Paper Salvage was a part of a programme launched by the British Government in 1939 at the outbreak of the Second World War to encourage the recycling of materials to aid the war effort, and which continued to be promoted until 1950.

History

The compulsory recycling – or, as it was known, salvage – of paper in wartime and postwar Britain focused primarily on raising household collections. The scheme formed a key part of a wider National Salvage Campaign comparable to the American Salvage for Victory campaign. It was inextricably linked to military and economic concerns and drew upon the experience of the First World War when prices had been driven up by the disruption to imports.

Drawing on this experience, a special Directorate was set up within the Ministry of Supply on 11 November 1939 and a Salvage Controller was appointed soon after.[1]

Initially the campaign focused on exhortation. Municipal authorities were required to submit targets and collection statistics to Whitehall, whilst housewives were encouraged to sort their waste.

As the war progressed controls were tightened: salvage became compulsory in late 1940 (initially for local authorities with more than 10,000 inhabitants this was extended to smaller towns a year later covering an estimated 43million people) and, from 1942, those refusing to sort their waste could be fined £2500 and face two years in prison.[2]

Locally, the scheme was run by over a hundred thousand volunteer salvage stewards who manned depots and encouraged the sorting of waste. Nationally, even the Royal family became involved, with Princess Elizabeth urging housewives to follow her lead.

The scheme was retained after war to help hasten the transition to peace. Following an economic crisis in 1947 efforts were redoubled and newspaper adverts explained how every ton of paper saved was equal to 2,956,800 cigarettes; 12,000 square feet (1,100 m2) of ceiling board; 17,000 sheets of brown wrapping paper or 201,600 books of matches.[3][4]

Counter-campaign

The British Records Association, concerned that over-enthusiasm might lead to the destruction of valuable archives, ran a much smaller-scale but vigorous counter-campaign to safeguard records that might be of current or future historical interest. It produced a leaflet using the slogan "Look before you throw", of which 33,000 copies had been distributed by the end of 1943.[5][6]

Results

According to government figures, less than 1,000 tons of scrap paper was salvaged each week in Britain before the war. By 1940, local authority collections had risen to 248,851 tons a year (30.8 per cent of total collections). This rose to a peak of 433,405 tons in 1942 (49.6 per cent of all collections); by which point 60 per cent of all new paper derived from recycled sources.[7]

Collection figures dropped to c.200,000 tons a year after the war but rose again in 1948 when 311,577 tons were collected by local authorities.[8]

With the price of scrap paper fixed at c.£5 a ton for a mixed bundle (compared to 5s before the war) rising for higher grades, this contributed between £3 and £5m to the economy.

However, government interest in its enforcement fluctuated: especially after 1947. Compulsion was removed on 30 June 1949, the Office of Paper Control wound up on 31 December, the Salvage Directorate was abolished on 30 March 1950 and price controls on 24 April 1950.[9][10]

After this point, the scheme gradually and unevenly died away and British paper mills were forced to import waste paper from the Netherlands, Sweden and Norway.[11]

References

- Riley, Mark (2008). "From Salvage to Recycling – New Agendas or Same Old Rubbish". Area. 40 (1): 79–89 (81). doi:10.1111/j.1475-4762.2008.00791.x.

- The Economist. 8 March 1941. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - The National Archives (TNA), INF 2/70: "Central Office of Information: Domestic Fuel Economy & Waste Paper Salvage Campaigns

- TNA, INF 2/104: "Ministry of Supply: Salvage Campaign"

- Bond, M. F. (1962). "The British Records Association and the Modern Archive Movement". In Hollaender, A. E. J. (ed.). Essays in Memory of Sir Hilary Jenkinson. London: Society of Archivists. pp. 69–77 (75–7).

- Harris, Oliver D. (1989). "'The Drudgery of Stamping': a physical history of the Records Preservation Section". Archives. 19: 3–17 (10).

- TNA, BT 64/3708: "Interdepartmental Committee on Salvage: Interim Report".

- "Waste Paper Salvage in 1948". Board of Trade Journal. 156 (2718): 137. 22 January 1949.

- "Ten Years Work of the Directorate of Salvage and Recovery". Board of Trade Journal. 158 (2780): 653. 1 April 1940.

- TNA, BT 64/1537: "Paper. Waste Materials. Relaxations in Price Control".

- "Questions Asked and Answered in Parliament". Board of Trade Journal. 158 (2780): 131. 15 July 1950.

Further reading

- Cooper, Tim (2008). "Challenging the "Refuse Revolution": War, Waste and the Rediscovery of Recycling, 1900–50"". Historical Research. 81 (214): 710–731. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2281.2007.00420.x. hdl:10036/28893.

- Irving, Henry (2016). "Paper salvage in Britain during the Second World War" (PDF). Historical Research. 89 (244): 373–93. doi:10.1111/1468-2281.12135.