Paolo Rolli

Paolo Antonio Rolli (13 June 1687 – 20 March 1765) was an Italian librettist, poet and translator.[1]

Biography

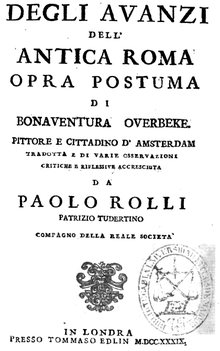

Paolo Rolli was born in Rome, Italy and like Metastasio was trained by Gian Vincenzo Gravina. The earl of Burlington brought him to England, which he commemorates in the dedication of his opera of “Astarte” to his noble patron, who attached him to the court as master of the Tuscan language to the princesses. He was Italian tutor to Caroline of Ansbach and then undertook the same role in London from 1715 to 1744 for her children Frederick, Amelia and Caroline[2]. During this period, he wrote librettos for numerous Italian operas including Handel's Floridante (1721), Muzio Scevola (1722), Riccardo Primo (1927) and Deidamia (1741) and Nicola Porpora's La festa d'Imeneo (1736) and Orfeo (1736)[3]. He also worked frequently with composer Giovanni Bononcini writing and adapting numerous librettos for him including his popular Griselda (1722). In December 1729 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society.[4]

Rolli did not spend an inactive life in England: besides being opera poet to the Royal Academy of Music until it was broke up, teaching his language to the royal family, and many of the first nobility, he published Italian odes, songs and elegies in the manner of Catullus, which were much admired. Among the works Rolli published in London there is a new edition of Ariosto's Rime e Satire as early as 1716, only a few months after his arrival in London; in 1717 he published Alessandro Marchetti's translation of Lucretius' De Rerum Natura; then Il Pastor Fido followed in 1718. In 1729 he published the first complete Italian translation of Milton's Paradise Lost. Upon the death of queen Caroline, his royal protectress, in 1737, he left England and returned to Italy, where he died in Todi in 1767, leaving behind him a very curious cabinet, and a rich library of well-chosen books.[1]

In Dichtung und Wahrheit (Poetry and Truth), Goethe explained that he learned by heart Rolli's canzonet Solitario Bosco Ombroso, performed by his “old Italian teacher named Giovanizzi” even before he knew a word of Italian.

Works

- Rime. London: Pickard. 1717.

- Canzonette e cantate. London: Pickard. 1727.

- De' Poetici Componimenti del signor Paolo Rolli (Venice 1753, 1761; Nice 1782).

- Carlo Calcaterra, ed. (1926). Liriche. Turin: UTET.

- Componimenti poetici in vario genere (Verona, 1744).

References

- Paolo Rolli at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- George E. Dorris, Paolo Rolli and the Italian Circle in London, 1715–1744 (Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 1967), page 145

- R. A. Streatfeild, 'Handel, Rolli, and Italian Opera in London in the Eighteenth Century', The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 3, No. 3 (Jul., 1917), pp. 428-445

- "Library Collection – Fellow details". The Royal Society. Retrieved 8 October 2010.

Bibliography

- Sciommeri, Giacomo (2018). "Dolcissima fassi la musica e la favella" - Paolo Rolli poeta per musica europeo. Roma: NeoClassica. ISBN 978-88-9374-025-8.

- F. Viglione (1913). "Paolo Rolli and the Society for the Encouragement of Learning". The Modern Language Review. 8 (2): 200–201. doi:10.2307/3713109. JSTOR 3713109.

- R. A. Streatfeild (1917). "Handel, Rolli, and Italian Opera in London in the Eighteenth Centurt". The Musical Quarterly. 3 (3): 428–445. doi:10.1093/mq/III.3.428. JSTOR 738033.

- George E. Dorris (1963). "Goethe, Rolli, and 'Solitario bosco ombroso'". The Journal of the Rutgers University Libraries. 26 (2): 33–35. doi:10.14713/jrul.v26i2.1421.

- George E. Dorris (1965). "Paolo Rolli and the First Italian Translation of Paradise Lost". Italica. 42 (2): 213–225. doi:10.2307/476915. JSTOR 476915.