Pancake graph

In the mathematical field of graph theory, the pancake graph Pn or n-pancake graph is a graph whose vertices are the permutations of n symbols from 1 to n and its edges are given between permutations transitive by prefix reversals.

| Pancake graph | |

|---|---|

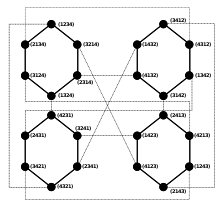

The pancake graph P4 can be constructed recursively from 4 copies of P3 by assigning a different element from the set {1, 2, 3, 4} as a suffix to each copy. | |

| Vertices | |

| Edges | |

| Girth | 6, if n > 2 |

| Chromatic number | see in the article |

| Chromatic index | n − 1 |

| Genus | see in the article |

| Properties | Regular Hamiltonian Cayley Vertex-transitive Maximally connected Super-connected Hyper-connected |

| Notation | Pn |

| Table of graphs and parameters | |

Pancake sorting is the colloquial term for the mathematical problem of sorting a disordered stack of pancakes in order of size when a spatula can be inserted at any point in the stack and used to flip all pancakes above it. A pancake number is the minimum number of flips required for a given number of pancakes. Obtaining the pancake number is equivalent to the problem of obtaining the diameter of the pancake graph.[1]

The pancake graph of dimension n, Pn, is a regular graph with vertices. Its degree is n − 1, hence, according to the handshaking lemma, it has edges. Pn can be constructed recursively from n copies of Pn−1, by assigning a different element from the set {1, 2, …, n} as a suffix to each copy.

Results

Pn (n ≥ 4) is super-connected and hyper-connected.[2]

Chromatic properties

There are some known graph coloring properties of pancake graphs.

A Pn (n ≥ 3) pancake graph has total chromatic number , chromatic index .[5]

There are effective algorithms for the proper (n−1)-coloring and total n-coloring of pancake graphs.[5]

For the chromatic number the following limits are known:

If , then

if , then

if , then

The following table discusses specific chromatic number values for some small n.

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

| 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4? | 4? | 4? | 4? | 4? | 4? | 4? | 4? | 4? |

Cycle enumeration

In a Pn (n ≥ 3) pancake graph there is always at least one cycle of length ℓ, when (but there are no cycles of length 3, 4 or 5).[6] It implies that the graph is Hamiltonian and any two vertices can be joined by a Hamiltonian path.

About the 6-cycles of the Pn (n ≥ 4) pancake graph: every vertex belongs to exactly one 6-cycle. The graph contains independent (vertex-disjoint) 6-cycles.[7]

About the 7-cycles of the Pn (n ≥ 4) pancake graph: every vertex belongs to 7-cyles. The graph contains different 7-cycles.[8]

About the 8-cycles of the Pn (n ≥ 4) pancake graph: the graph contains different 8-cycles; a maximal set of independent 8-cycles contains of those.[7]

Diameter

The pancake sorting problem (obtaining the pancake number) and obtaining the diameter of the pancake graph are equivalents. One of the main difficulties in solving this problem is the complicated cycle structure of the pancake graph.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | |

| 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

The pancake number, which is the minimum number of flips required to sort any stack of n pancakes has been shown to lie between 15/14n and 18/11n (approximately 1.07n and 1.64n,) but the exact value remains an open problem.[9]

In 1979, Bill Gates and Christos Papadimitriou[10] gave an upper bound of 5/3n. This was improved, thirty years later, to 18/11n by a team of researchers at the University of Texas at Dallas, led by Founders Professor Hal Sudborough[11] (Chitturi et al., 2009[12]).

In 2011, Laurent Bulteau, Guillaume Fertin, and Irena Rusu[13] proved that the problem of finding the shortest sequence of flips for a given stack of pancakes is NP-hard, thereby answering a question that had been open for over three decades.

Burnt pancake graph

In a variation called the burnt pancake problem, the bottom of each pancake in the pile is burnt, and the sort must be completed with the burnt side of every pancake down. It is a signed permutation, and if a pancake i is "burnt side up" a negative element i` is put in place of i in the permutation. The burnt pancake graph is the graph representation of this problem.

A burnt pancake graph is regular, its order is , its degree is .

For its variant David S. Cohen (David X. Cohen) and Manuel Blum proved in 1995, that (when the upper limit is only true if ).[14]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

| 1 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 15 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 21 |

The girth of a burnt pancake graph is:[3]

Other classes of pancake graphs

Both in the original pancake sorting problem and the burnt pancake problem, prefix reversal was the operation connecting two permutations. If we allow non-prefixed reversals (as if we were flipping with two spatulas instead of one) then four classes of pancake graphs can be defined. Every pancake graph embeds in all higher-order pancake graphs of the same family.[3]

| Name | Notation | Explanation | Order | Degree | Girth (if n>2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unsigned prefix reversal graph | The original pancake sorting problem | ||||

| unsigned reversal graph | The original problem with two spatulas | ||||

| signed prefix reversal graph | The burnt pancake problem | ||||

| signed reversal graph | The burnt pancake problem with two spatulas |

Applications

Since pancake graphs have many interesting properties such as symmetric and recursive structures (they are Cayley graphs, thus are vertex-transitive), sublogarithmic degree and diameter, and are relatively sparse (compared to e.g. hypercubes), much attention is paid to them as a model of interconnection networks for parallel computers.[4][15][16][17] When we regard the pancake graphs as the model of the interconnection networks, the diameter of the graph is a measure that represents the delay of communication.[18][19]

Pancake flipping has biological applications as well, in the field of genetic examinations. In one kind of large-scale mutations, a large segment of the genome gets reversed, which is analogous to the burnt pancake problem.

References

- Asai, Shogo; Kounoike, Yuusuke; Shinano, Yuji; Kaneko, Keiichi (2006-09-01). Computing the Diameter of 17-Pancake Graph Using a PC Cluster. Euro-Par 2006 Parallel Processing: 12th International Euro-Par Conference. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 4128. pp. 1114–1124. doi:10.1007/11823285_117. ISBN 978-3-540-37783-2.

- Deng, Yun-Ping; Xiao-Dong, Zhang (2012-03-31). "Automorphism Groups of the Pancake Graphs". Information Processing Letters. 112 (7): 264–266. arXiv:1201.0452. doi:10.1016/j.ipl.2011.12.010.

- Compeau, Phillip E.C. (2011-09-06). "Girth of pancake graphs". Discrete Applied Mathematics. 159 (15): 1641–1645. doi:10.1016/j.dam.2011.06.013.

- Nguyen, Quan; Bettayeb, Said (2009-11-05). "On the Genus of Pancake Network" (PDF). The International Arab Journal of Information Technology. 8 (3): 289–292.

- Konstantinova, Elena (2017-08-01). "Chromatic Properties of the Pancake Graphs". Discussiones Mathematicae Graph Theory. 37 (3): 777–787. doi:10.7151/dmgt.1978.

- Sheu, Jyh-Jian; Tan, Jimmy J. M. (2006). "Cycle embedding in pancake interconnection networks" (PDF). The 23rd Workshop on Combinatorial Mathematics and Computation Theory.

- Konstantinova, E.V.; Medvedev, A.N. (2013-04-26). "Small cycles in the Pancake graph" (PDF). Ars Mathematica Contemporanea. 7: 237–246. doi:10.26493/1855-3974.214.0e8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-12-15. Retrieved 2017-08-04.

- Konstantinova, E.V.; Medvedev, A.N. (2010-04-01). "Cycles of length seven in the pancake graph". Diskretn. Anal. Issled. Oper. 17 (5): 46–55. doi:10.1016/j.tcs.2008.04.045.

- Fertin, G. and Labarre, A. and Rusu, I. and Tannier, E. and Vialette, S. (2009). Combinatorics of Genome Rearrangements. The MIT Press. ISBN 9780262062824.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Gates, W.; Papadimitriou, C. (1979). "Bounds for Sorting by Prefix Reversal" (PDF). Discrete Mathematics. 27: 47–57. doi:10.1016/0012-365X(79)90068-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-10. Retrieved 2017-08-04.

- "Team Bests Young Bill Gates With Improved Answer to So-Called Pancake Problem in Mathematics". University of Texas at Dallas News Center. September 17, 2008. Archived from the original on April 5, 2012. Retrieved November 10, 2008.

A team of UT Dallas computer science students and their faculty adviser have improved upon a longstanding solution to a mathematical conundrum known as the pancake problem. The previous best solution, which stood for almost 30 years, was devised by Bill Gates and one of his Harvard instructors, Christos Papadimitriou, several years before Microsoft was established.

- Chitturi, B.; Fahle, W.; Meng, Z.; Morales, L.; Shields, C. O.; Sudborough, I. H.; Voit, W. (2009-08-31). "An (18/11)n upper bound for sorting by prefix reversals". Theoretical Computer Science. Graphs, Games and Computation: Dedicated to Professor Burkhard Monien on the Occasion of his 65th Birthday. 410 (36): 3372–3390. doi:10.1016/j.tcs.2008.04.045.

- Bulteau, Laurent; Fertin, Guillaume; Rusu, Irena (2015). "Pancake Flipping Is Hard". Journal of Computer and System Sciences. 81 (8): 1556–1574. arXiv:1111.0434. doi:10.1016/j.jcss.2015.02.003.

- David S. Cohen, Manuel Blum: On the problem of sorting burnt pancakes. In: Discrete Applied Mathematics. 61, Nr. 2, 1995, S. 105–120. DOI:10.1016/0166-218X(94)00009-3.

- Akl, S.G.; Qiu, K.; Stojmenović, I. (1993). "Fundamental algorithms for the star and pancake interconnection networks with applications to computational geometry". Networks. 23 (4): 215–225. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.363.4949. doi:10.1002/net.3230230403.

- Bass, D.W.; Sudborough, I.H. (March 2003). "Pancake problems with restricted prefix reversals and some corresponding Cayley networks". Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing. 63 (3): 327–336. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.27.7009. doi:10.1016/S0743-7315(03)00033-9.

- Berthomé, P.; Ferreira, A.; Perennes, S. (December 1996). "Optimal information dissemination in star and pancake networks". IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems. 7 (12): 1292–1300. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.44.6681. doi:10.1109/71.553290.

- Kumar, V., Grama, A., Gupta, A., Karypis, G.: Introduction to Parallel Computing: Design and Analysis of Algorithms. Benjamin/Cummings (1994)

- Quinn, M.J.: Parallel Computing: Theory and Practice, second edition. McGrawHill (1994)