Panagia Apsinthiotissa

Panagia Apsinthiotissa or Absinthiotissa (Greek: Παναγία Αψινθιώτισσα) is a Greek Orthodox monastery located at the southern foot of the Pentadaktylos range in the Republic of Cyprus. The nearest settlements are Sychari (Συγχαρί, Tr. Kaynakköy) and Vouno (Βουνό, Tr. Taşkent). The site presently falls within the de facto Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus in Girne District.

History

The name Panagia Apsinthiotissa refers to Panagia, the Orthodox name for the Virgin Mary, and Absinthe, a toponym derived from the cultivation of wormwood (Artemisia absinthium) shrubs in the area. According to a local legend, the monastery was named after a wormwood bush that covered the mouth of the cave in which a monk had hidden an icon of the Virgin Mary in order to save it during the period of Byzantine Iconoclasm. Many years later, after the restoration of images, the inhabitants of the area saw a strange light shining from this point on the mountain. They found the icon and built a monastery immediately below in the name of the Virgin and the wormwood bush. The monastery was known in western medieval sources as the Abbey of Abscithi or Apinthi.[1] Sometimes it was simply called Psithia, as in the Chronicle of Georgios Boustronios.[2]

The monastery was probably established in the eleventh or twelfth century as a Byzantine imperial foundation and continued to enjoy a degree of prominence in the Lusignan and Venetian periods. Leontios, the abbot in about 1222, was one of the delegates sent to report the plight of the Orthodox Church under Latin jurisdiction to the Patriarch Germanos II in the Empire of Nicaea. Neophytus, Archbishop of Cyprus, was also in Nicaea at the time, having been banished by the Latin authorities for refusing to take an oath of obedience to the Roman Pontiff.[3] Many years later, Boustronios tells us that the Queen of Cyprus worshipped at the monastery in 1486, the implication being that Panagia Apsinthiotissa was under the Roman Church.[4] He also reports that pilgrimages were made to Apinthi and Antiphonitis on the fifteenth of August by all the people of Kyrenia.[5] After the Ottoman conquest, the monastery became the property of the Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem and subordinate to the nearby Monastery of Saint Chrysostom in Koutsoventis.

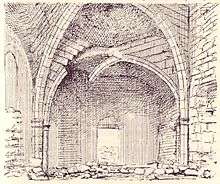

Architecture

The main church of the monastery appears to have been built in the twelfth century and has a cross-in-square plan of the Byzantine type surmounted by a high dome. The narthex, on the west side, has simple Gothic rib vaulting and probably dates to the fifteenth century.[6] Writing in 1918, George H. Everett Jeffery, described the establishment as a ruin.[7]

Recent developments

After the opening of checkpoints between the two parts of Cyprus in 2003, a group of Greek and Turkish architects associated with the Cyprus Civil Engineers and Architects Association (CCEAA) and the Chamber of Cyprus Turkish Architects began listing and documenting building as a way of preserving, safeguarding and operating the religious buildings of Cyprus that were abandoned after 1974. The monastery of Panagia Apsinthiotissa is among the places documented by this bi-communal group.

References

- Rupert Gunnis, Historic Cyprus (London, 1936, reprint ed. 1973), p. 434. J. Hackett, A History of the Orthodox Church of Cyprus (London, 1901), p. 90.

- Richard McGillivray Dawkins, The Chronicle of George Boustronious, 1456-1489 (Melbourne, 1964).

- Hackett, A History of the Orthodox Church of Cyprus, pp. 89-90 and 309.

- Dawkins, The Chronicle of George Boustronious, 1456-1489, p. 59.

- Dawkins, The Chronicle of George Boustronious, 1456-1489, p. 35.

- Camille Enlart, L'art gothique et la renaissance en Chypre : illustré de 34 planches et de 421 figures (Paris, E. Leroux, 1899)

- George H. Everett Jeffery, A Description of the Historic Monuments of Cyprus (Nicosia, 1918, reprint. ed. London, 1983), p. 275.

External links

Tassos Papacostas, Inventory of Byzantine Churches on Cyprus, London 2015, ISBN 978-1-897747-31-5

List and evaluation of Greek and Turkish Religious Buildings