Painted Chamber

The Painted Chamber was part of the medieval Palace of Westminster. It was gutted by fire in 1834, and has been described as "perhaps the greatest artistic treasure lost in the fire".[1] The room was re-roofed and re-furnished to be used temporarily by the House of Lords until 1847, and it was demolished in 1851.

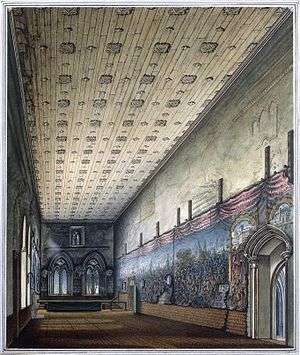

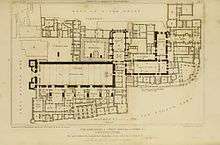

The chamber was built by Henry III, parallel to St Stephen's Chapel. It is said that the site was previously occupied by a room in which Edward the Confessor had died.[2] The new chamber was intended for use by the king primarily as a private apartment, but was also used as a reception room, and it was constructed and decorated to impress visitors. The chamber was relatively long and narrow, measuring approximately 82 by 28 feet (25.0 m × 8.5 m), with a state bed (for example the marriage bed of Henry VII) towards one end under a painting of Edward the Confessor. One wall included a squint providing a view of the altar in a chapel next door, so the king could view religious services from the chamber. The ceiling of wooden planks with decorative bosses survived until at least 1819, when it was replaced with plaster.

The chamber was originally named the King's Chamber. It adjoined a new Queen's Chamber to the south, later used for meetings of the House of Lords until it moved to the Lesser Hall or White Chamber in 1801; the Queen's Chamber was demolished along with other buildings in 1823.[3] The King's Chamber came to be known as the Painted Chamber after its decorative wall paintings, of Virtues and Vices, and Bible figures. The brightly coloured paintings took 60 years to complete, starting in 1226. The original paintings were repaired in 1263 after they were damaged by fire, and again in 1267 after they were damaged by a mob that invaded the palace. The murals were supplemented by paintings commissioned by subsequent monarchs.

The Painted Chamber was later neglected, and the walls were whitewashed, papered and covered by tapestries as depicted in the watercolour of William Capon from 1799. In 1800 the original murals were detected under the whitewash, but it was only in 1819 that they were fully revealed. In that year the Society of Antiquarians commissioned the artist and antiquarian Charles Stothard to make watercolour copies of the murals; and Thomas Crofton Croker, clerk of works at Westminster and an amateur artist, made his own somewhat more complete copies in watercolour, now held by the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Ashmolean Museum. During repairs in 1816, four ceiling paintings—one seraph and three prophets painted on oak panels—were removed by Adam Lee, the "Labourer in Trust" at Westminster. After passing through several owners, two of them (the seraph and a prophet) resurfaced in Bristol in 1993 and were acquired by the British Museum two years later. The whereabouts of the other two are not known. A wooden patera from the original ceiling is preserved in the Museum bequeathed by the architect Sir John Soane, clerk of works at Westminster until 1794 and 30 years later responsible for modifications there.[4][5]

The Painted Chamber survived largely intact for over 600 years. In the later 13th century, some of the early English Parliaments summoned by Edward I met in the Painted Chamber, and the room continued to be used for important state ceremonies, including the State Opening of Parliament.[6] The House of Lords met nearby in the Queen's Chamber and later the White Chamber. The House of Commons, however, did not have a chamber of its own; it sometimes held its debates in the Chapter House of Westminster Abbey until a permanent home in the former St Stephen's Chapel became available in the 16th century. The Painted Chamber, between the chambers used by the House of Lords and the House of Commons, was used for the State Opening, and when both Houses met in conference.[7]

The room was also used for other state purposes. At the trial of Charles I, the evidence of the witnesses summoned was heard in the Painted Chamber rather than Westminster Hall.[8] The death warrant of Charles I was signed here, and the body of Charles II rested the night in this chamber before being interred at Westminster Abbey. It was also used for the lying-in-state of Elizabeth Claypole (the daughter of Oliver Cromwell), William Pitt the Elder, and William Pitt the Younger.[9] In around 1820, the room was being used for the Court of Claims.

The chamber was gutted in the devastating fire in 1834, but the thick medieval walls survived. Wood salvaged from the Painted Chamber was used to make souvenirs. The room was re-roofed and re-furnished to be used temporarily by the House of Lords for the State Opening of Parliament on 23 February 1835. It was used by the House of Lords until 1847, and finally demolished in 1851.

References

- The Fire of 1834 and the Old Palace of Westminster, parliament.uk

- Henry III and the Painted Chamber, parliament.uk

- The Day Parliament Burned Down, Caroline Shenton, p.9-10

- Panel Paintings from the Palace of Westminster, London, British Museum

- Tudor-Craig, Pamela (1957), "The Painted Chamber at Westminster", Archaeological Journal, 114: 92–105

- The Day Parliament Burned Down, Caroline Shenton, p.200-203

- The Painted Chamber, All Change at the Palace of Westminster, BBC History, 2 February 2005. The many conferences between Commons and Lords that resulted in the Petition of Right were held in the Painted Chamber. E.g. Journal of the House of Lords: Volume 3, 1620-1628 (London, 1767-1830), for 4/7/1728, the date of the first such conference, states that Commons asked for a conference on "the Liberty of the Subject" and "some ancient Fundamental Liberties of the Kingdom.Answered: The Lords will give them a Meeting, by a Committee of both Houses, at Three this Afternoon, in the Painted Chamber."

- Paul Binski, The Painted Chamber at Westminster. London: Society of Antiquaries, 1986. (Occasional Paper, n.s. 9.)

- Walter Thornbury, 'The royal palace of Westminster', in Old and New London: Volume 3 (London, 1878), pp. 491-502

External links

- Oak ceiling ornament from Painted Chamber, Sir John Soane's Museum

- The Painted Chamber and St. Stephen's Chapel after the Fire, 1834, parliament.uk

- Interior of Painted Chamber after the Fire 1834, parliament.uk