Oxford Town Hall

Oxford Town Hall is a public building in St Aldate's Street in central Oxford, England.[1] It is both the seat of Oxford City Council and a venue for public meetings, entertainment and other events. It is also includes the Museum of Oxford. Although Oxford is a city with its own charter, the building is referred to as the "Town Hall". It is Oxford's third seat of government to have stood on the same site. The present building, completed in 1897, is Grade II* listed.[2]

| Oxford Town Hall | |

|---|---|

.jpg) View from the southwest | |

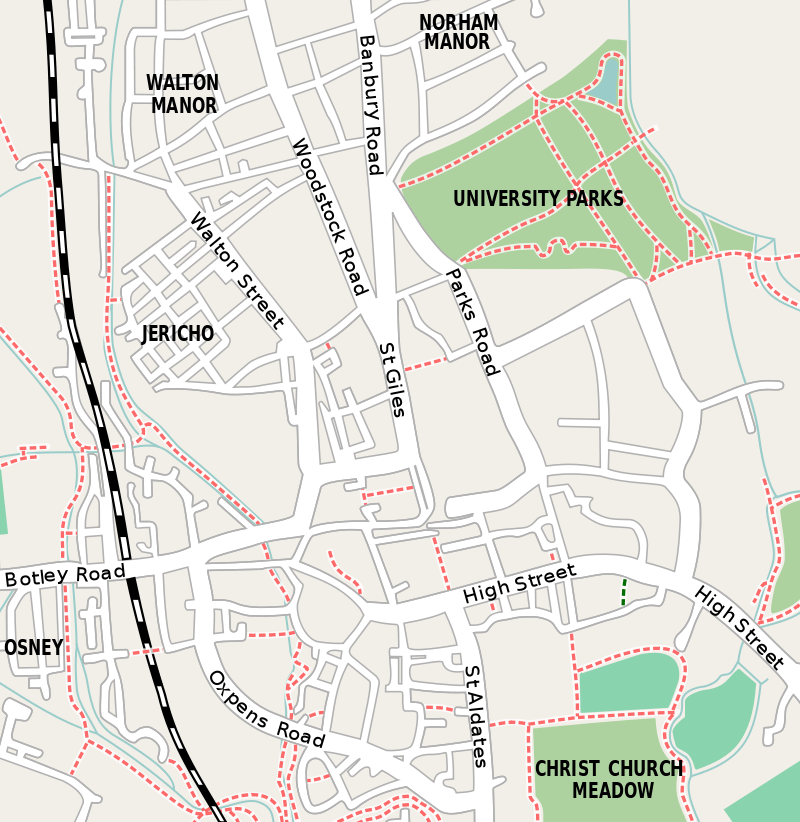

Location within Oxford city centre | |

| General information | |

| Type | Town hall, museum, former library and police station |

| Architectural style | Jacobethan |

| Classification | |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Designated | 12 January 1954 |

| Reference no. | 1047153 |

| Location | St Aldate's, Oxford |

| Coordinates | 51.7516°N 1.2569°W |

| Construction started | 1893 |

| Completed | 1897 |

| Renovated | Main Hall repainted in 2015 |

| Cost | £100,000 |

| Owner | Oxford City Council |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Henry Hare |

| Website | |

| Oxford Town Hall | |

History

Oxford's guildhall was created by substantially repairing or rebuilding a house on the current site in about 1292.[3] It was replaced by a new building, designed by Isaac Ware in the Italianate style in 1752.[3] In 1891, an architectural design competition was held for a new building on the same site. The local architect Henry Hare won with a Jacobethan design. The 1752 building was demolished in 1893. Hare's new building included new premises for Oxford's Crown and County Courts, central public library and police station as well as the city council.[2] The Prince of Wales opened the new building in May 1897, about a month before the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria.[4]

University of Oxford undergraduates were expected to mount a large demonstration for the opening, so a detachment of the Metropolitan Police Mounted Branch was deployed to reinforce the small Oxford City Police force.[4] The Metropolitan officers were unused to Oxford undergraduates, and considered the boisterous crowd a danger. The officers attacked the crowd with batons, causing several serious injuries. The crowd reciprocated, unhorsing one officer and trampling him.[4] A young law don, FE Smith, who had taken no part in the violence, saw police mishandling his college servant. Smith went to rescue his servant but was arrested. He became the first prisoner in one of the cells of the new police station in the new Town Hall. Smith was charged with obstructing police officers in the execution of their duty, but at his trial the young lawyer was found not guilty.[4]

The police station was at the rear in Blue Boar Street. It was completed later than the rest of the building, but the Oxford City Police force was able to move there from its former station in Kemp Hall by the turn of the century.[4] The City Council was accused of greatly exceeding the budget it set for the building project. In 1905 Henry Taunt published a leaflet in which he stated that the building was meant to cost £47,000 but ended up costing £100,000.[5]

In the First World War the building was converted into the Town Hall section of the 3rd Southern General Hospital. From 1916 it specialised in treating soldiers suffering from malaria.[6]

Oxford City Police moved to a new police station further down St Aldate's in 1936 and the central public library moved to new facilities at Westgate Centre in Queen Street which were completed in 1972.[7]

The town hall was the headquarters of the county borough for much of the 20th century and remained the seat of government after Oxford City Council was formed in 1974.[8]

Works of art in the town hall include a portraits of King James II,[9] Queen Anne[10] and the Duke of Marlborough by Godfrey Kneller,[11] a painting depicting the Rape of the Sabine Women by Pietro da Cortona[12] and a painting depicting Saint Peter by Francesco Fontebasso.[13]

References

- Hibbert 1988, pp. 454–455.

- Historic England. "Town Hall, Municipal Buildings and Library (Grade II*) (1047153)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- Chance, Eleanor; Colvin, Christina; Cooper, Janet; Day, C J; Hassall, T G; Jessup, Mary; Selwyn, Nesta (1979). "'Municipal Buildings', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 4, the City of Oxford, ed. Alan Crossley and C R Elrington". London: British History Online. pp. 331–336. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Rose 1979, p. 5.

- Graham 1973, 3. His Character and Personality.

- Jenkins, Stephanie. "Third Southern General Hospital in Oxford in World War I". Oxford History. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- Michael Dewe, Planning public library buildings: concepts and issues for the librarian. Ashgate Publishing, 2006, page 126. ISBN 978-0-7546-3388-4.

- Local Government Act 1972. 1972 c.70. The Stationery Office Ltd. 1997. ISBN 0-10-547072-4.

- Kneller, Godfrey. "James II (1633–1701)". Art UK. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Kneller, Godfrey. "Queen Anne (1665–1714)". Art UK. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Kneller, Godfrey. "John Churchill (1650–1722), Duke of Marlborough". Art UK. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Da Cortona, Pietro. "The Rape of the Sabines". Art UK. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Fontebasso, Francesco. "The Penitent St Peter". Art UK. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

Sources and further reading

- Graham, Malcolm (1973). Henry Taunt of Oxford: A Victorian Photographer. Headington: Oxford Illustrated Press. ISBN 0-902280-14-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hibbert, Christopher, ed. (1988). "Town Hall". The Encyclopaedia of Oxford. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-39917-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rose, Geoff (1979). A Pictorial History of the Oxford City Police. Oxford: Oxford Publishing Co. ISBN 0-86093-094-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sherwood, Jennifer; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1974). Oxfordshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. p. 302. ISBN 0-14-071045-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tyack, Geoffrey (1998). Oxford An Architectural Guide. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 259–262. ISBN 0-19-817423-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oxford Town Hall. |

- "Virtual Tour of the Oxford Town Hall". Oxford City Council Virtual Tours. Department of Chemistry, University of Oxford. 2004.

- Jenkins, Stephanie (13 September 2012). "The new Town Hall, Oxford". Oxford History, Mayors & Lord Mayors.