Oughterard

Oughterard (Irish: Uachtar Ard)[2] is a small town on the banks of the Owenriff River close to the western shore of Lough Corrib in County Galway, Ireland. The population of the town in 2016 was 1,318.[1] It is located about 26 km northwest of Galway on the N59 road. Oughterard is on the border of the Connemara region, and is the chief angling centre on Lough Corrib.[3]

Oughterard Uachtar Ard | |

|---|---|

Town | |

| |

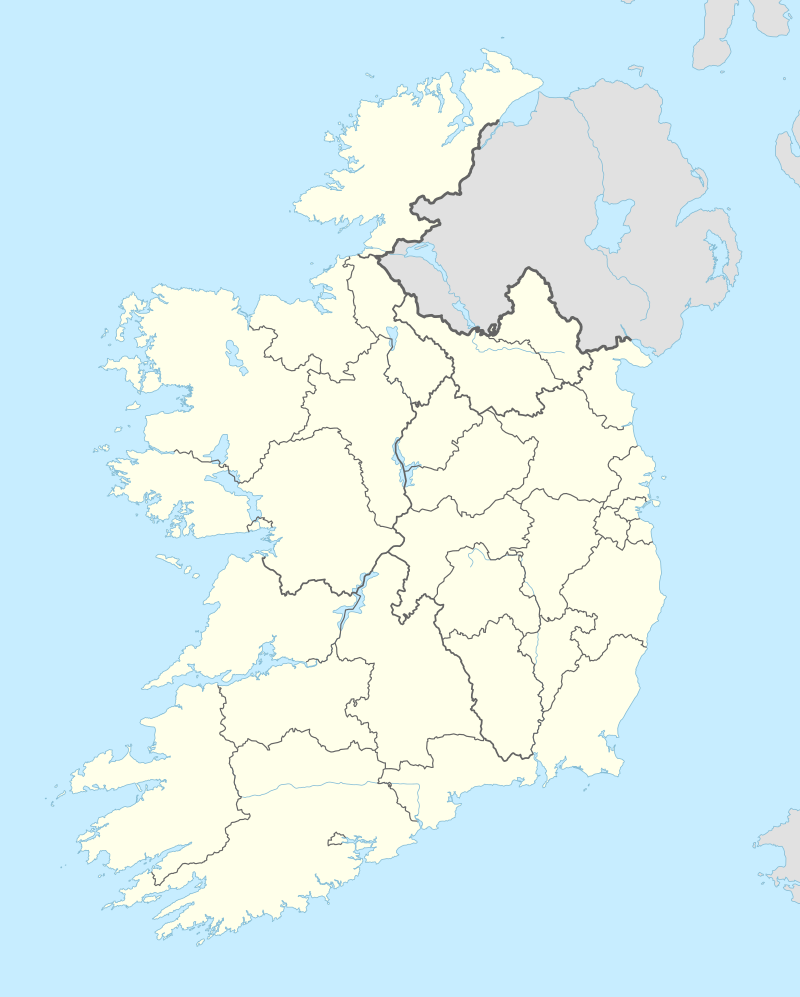

Oughterard Location in Ireland | |

| Coordinates: 53°25′00″N 9°20′00″W | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Province | Connacht |

| County | County Galway |

| Elevation | 68 m (223 ft) |

| Population (2016)[1] | 1,318 |

| Irish Grid Reference | M113415 |

Places of interest

Three kilometres outside the town stand the ruins of Aughnanure Castle, a well-preserved example of a medieval tower house.[4] Much of the surrounding area was occupied by the O'Flaherty clan, but was taken over by Walter de Burgh, 1st Earl of Ulster, in 1256. Ross Castle is also located a number of kilometres outside Oughterard. The mansion, which is visible today, was built by the Martin family in the 17th century but there is some evidence still present of the original castle structure, built in the 15th century by the O'Flaherty family, in its foundation.

The 'Quiet Man Bridge' is located 8 kilometres past Oughterard, down the Leam Road, which was the setting for the 1950s film The Quiet Man starring John Wayne and Maureen O'Hara.

Also close to Oughterard, the Glengowla Mines (abandoned in 1865) is a "show mine" with exhibits on the lead and silver mining history of the area.[5][6]

.jpg)

Transport

Oughterard railway station opened on 1 January 1895 and closed on 29 April 1935. There are daily buses going from and to Galway and Clifden along the N59. City Link and Bus Éireann are the two bus services that travel to and from Galway.

Amenities

Oughterard has a primary school, 'Scoil Chuimín agus Caitríona',[7] and a co-educational voluntary secondary school, St Paul's.[8] As of early 2019, Oughterard's public library, based in the town's old courthouse, was closed for renovations.[9]

A former hotel on the outskirts of the town, the Connemara Gateway Hotel, attracted some controversy in 2019, when locals protested plans to convert the disused site into a direct provision centre.[10] Some locals protested against "inhumane direct provision centres",[11] with some members of the "Oughterard Says No to Direct Provision" group suggesting that "negative outside influences" had attempted to influence the protests, amid some accusations of racism.[12] After prolonged protests,[13] the tender for the centre was withdrawn.[14]

Sport

Sports clubs in the area include Oughterard GAA club (Corribdale), Oughterard Association Football Club (New Village), Oughterard Rugby Club (Cliden Road), and Corrib Basketball (Main Street).

Oughterard Golf Club, located outside the town, was incorporated in 1969 and developed in the early 1970s.[15]

People

- Tom Collins, filmmaker based in Oughterard[16]

- John Purcell, recipient of the Victoria Cross, was born in Kilcommonn near Oughterard[17]

- Joe Shaughnessy, a professional footballer with Southend United F.C., was born in Oughterard[18]

See also

- List of towns in the Republic of Ireland

References

- "Census 2016 Sapmap Area: Settlements Oughterard". Central Statistics Office (Ireland). Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- "Uachtar Ard/Oughterard". Placenames Database of Ireland. Government of Ireland - Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht and Dublin City University. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- O'Reilly, Peter (2003). Rivers of Ireland. 7 Corve St., Ludlow, Shropshire, UK: Merlin Unwine Books. p. 174. ISBN 1-873674-53-8.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Heritage Ireland - Aughnanure Castle". heritageireland.ie. Office of Public Works. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

the castle is a particularly well-preserved example of an Irish tower house

- "Glengowla Mines". Show Caves. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- "Glengowla Mines". Ask About Ireland. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- "Scoil Náisiúnta Uachtar Árd". OughterardNS.ie. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- "School Homepage". St Paul's Oughterard. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

St. Paul's Secondary School is a co-educational voluntary secondary school situated in Oughterard, Co. Galway

- "Lengthy Closure For Oughterard Library". galwayindependent.com. Galway Independent. 8 January 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- Bernie Ní Fhlatharta (11 September 2019). "Minister booed as Oughterard rejects direct provision centre". Irishtimes.com. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Shauna Bowers (28 September 2019). "Large crowd continues protest over direct provision centre in Oughterard". Irishtimes.com. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Sean Moncrieff (19 October 2019). "Was Oughterard about racism or a fear of the unknown?". Irishtimes.com. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Pat McGrath (1 October 2019). "Tender for Oughterard asylum seeker centre withdrawn". Rte.ie. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- "'It is disappointing': Govt reacts to decision to withdraw tender for Oughterard Direct Provision centre". Thejournal.ie. 1 October 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- "Oughterard Golf Club". oughterardheritage.org. Oughterard Culture and Heritage Group. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

[Oughterard Gortreevagh Golf Course Ltd] was incorporated on 3rd July 1969 [.and.] development of the Club took place during 1969, 1970, 1971 and 1972

- "Kings of the West". Connacht Tribune. 21 May 2013. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018.

- "John Purcell VC". vconline.org.uk. Victoria Cross Online. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- "Footballers and film stars – is this the most talented family in Galway?". Connacht Tribune. 21 May 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Oughterard. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oughterard. |