Oswald Croll

Oswald Croll or Crollius (c. 1563 – December 1609) was an alchemist, and professor of medicine at the University of Marburg in Hesse, Germany. A strong proponent of alchemy and using chemistry in medicine, he was heavily involved in writing books and influencing thinkers of his day towards viewing chemistry and alchemy as two separate fields.[1]

Croll received his doctorate in medicine in 1582 at Marburg, then continued studies at Heidelberg, Strasburg, and Geneva. After working as a tutor, he arrived in Prague in 1597. He remained there for two years, and again from 1602 until his death.[2] There, through Rudolf II, he came into contact with other alchemical writers such as Edward Kelley.

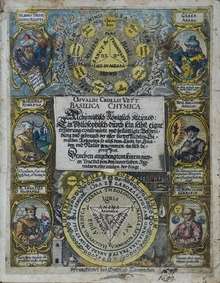

In 1608, Croll's opus magnum "Basilica Chymica" ("Chemical Basilica") was first published, self-described as containing a philosophick description, confirmed by the experience of [Croll's] own labours, and application of the choicest chymical remedies drawn from the light of Nature and of Grace.[3] It is a hefty summary of his researches, methods of preparation, and studies into chemical medicine or iatrochemistry. In 1609 his treatise "De signatura rerum" ("Treatise of signatures") was published. Some of his work pushed for the understanding and recognition of chemical compounds and medicinal value of herbs and other processes first put forth by Paracelsus.[4] It also discussed matters such as compound remedies, chemical organization and acted as an introduction to chemistry in later years. The second book covered alchemy's and chemistry's relation to other fields of science, especially botany, suggesting the use of the doctrine of signatures to determine the medical property of plants.

Croll died suddenly in 1609. His reputation and influence grew after his death, and was noted by Robert Burton in his Anatomy of Melancholy.[5] In 1618, Croll was deemed one of alchemy’s heroes in Johann Daniel Mylius’ Basilica Philosophica (1618 - Opus Medico-Chymicum, third book). An emblematic seal dedicated to him appears in this work alongside the motto:

Oswald Croll of Wetter, Disciple of the Philosophers: This knowledge is nothing but the secrets of wise teachers and Philosophers.[6]

Alchemical studies

Croll believed that chemistry and alchemy were two halves of a tightly related field, in the same way that organic and inorganic chemistry are related. He used the framework of Parcelsus' works to organize his beliefs about the geometrically important relationships between various forms of matter and alchemical reactions, from rectangles to megagons.[7]

- La royalle Chymie de Crollius . Lyon : Drobet, 1624 Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

- Oswaldi Crollii Basilica chymica : pluribus selectis et secretissimis propria manuali Experentia approbatis Descriptionibus, et Usu Remdiorum chymicorum selectissimorum. Genevae : Chouet, 1643 Digital edition / 1658 Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

References

- Allen G. Debus, The Chemical Philosophy: Paracelsian Science and Medicine in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (New York: Science History Publications, 1977), vol. 1, pp. 117-126

- Mark Haeffner. Dictionary of Alchemy: From Maria Prophetessa to Isaac Newton. p.94

- Stanislas Klossowski de Rola. The Golden Game: Alchemical Engravings of the Seventeenth Century. 1988. p. 157.

- Owen Hannaway, The Chemists and the Word: The Didactic Origins of Chemistry (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975).

- Peter Marshall. The Theatre of the World. Alchemy, Astrology and Magic in Renaissance Prague. p.131

- Stanislas Klossowski de Rola. The Golden Game: Alchemical Engravings of the Seventeenth Century. 1988. p. 155.

- Arthur Greenberg, 2007. From Alchemy to Chemistry in Picture and Story. John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-75154-5, ISBN 978-0-471-75154-0