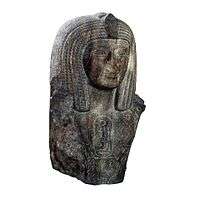

Osorkon Bust

The Osorkon Bust, also known as the Eliba'l Inscription is a bust of Egyptian pharaoh Osorkon I, discovered in Byblos (in today's Lebanon) in the nineteenth century. Like the Tabnit sarcophagus from Sidon, it is decorated with two separate and unrelated inscriptions – one in Egyptian hieroglyphics and one in Phoenician script. It was created in the early 10th century BC, and was unearthed in c.1881,[1] very likely in the Temple of Baalat Gebal.

| Osorkon Bust | |

|---|---|

The Osorkon Bust, showing the Phoenician inscription on either side of the Egyptian cartouche | |

| Material | Quartzite |

| Writing | Phoenician |

| Created | c. 900 BC |

| Discovered | 1881 |

| Present location | Louvre |

| Identification | AO 9502 |

The Egyptian writing is the prenomen of Osorkon, and the Phoenician is a dedication to Elibaal, the king of Byblos.

The details of the find were published in by French archaeologist René Dussaud in 1925.[1]

The bust is made of quartzite, and is 60 cm x 36 cm x 37.5 cm.[2]

Discovery

The first mention of the statue was by German archaeologist Alfred Wiedemann in 1884 in his Ägyptische Geschichte: German: zwei Fragmente einer grossen Steinstatue sind gleichfalls erhalten geblieben [Im Besitz des Herrn Meuricoffre zu Neapel.] In English: “two fragments of a large stone statue have also been preserved [owned by Mr. Meuricoffre at Naples.]”[3][4]

In 1895, Weidemann published the Egyptian hieroglyphs: German: Vor nahezu 15 Jahren hatte ich Gelegenheit im Landhause des H. Bankier Meuricoffre zu Neapel eine grosse Statue aus hartem Sandstein des Koenigs Osorkon I kennen zu lernen. Von ihr waren zwei Fragmente erhalten. Zunaechst die Buste, an deren Brust vorn stand, am Guertel befand sich der Cartouchenrest, am Ruekenpfeiler. Dann ein Theil der Basis mit darauf stehenden Fuss. In English: “ Almost 15 years ago I had the opportunity to visit the country house of the banker Meuricoffre of Naples to get to know a large statue made of hard sandstone of King Osorkon I. Two fragments were preserved from it. First the bust, on the chest of which stood at the front, on the belt there was the rest of the cartouches, and on the rock pillar. Then a part of the base with the foot.”[5]

Phoenician inscription

1. mš. z p‘l. ’lb‘l. mlk. gbl. byḥ [mlk. mlk gbl]

2. [lb]‘lt. gbl. ’dtw. t’rk. b‘lt [.gbl]

3. [ymt. ’]lb‘l. wšntw. ‘l[. gbl]

Translation:

1. Statue which Eliba‘al, king of Byblos, son of Yeḥi[milk, king of Byblos] made

2. [for the Ba]‘alat of Byblos, his Lady. May the Ba‘alat [of Byblos] prolong

3. [the days of E]liba‘al and the years over [Byblos]

Notes

- Vriezen 1951, p. 10.

- Louvre Osorkon Bust

- Ägyptische Geschichte, 1884, p. 553

- Dussaud, 1925, p. 101

- Recueil de travaux relatifs à la philologie et à l'archéologie égyptiennes et assyriennes; volume 17, 1895, p. 14

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Statue of Pharaoh Osorkon I-AO 9502. |

- Editio princeps: René Dussaud, Dédicace dune stame d’Osorkon Ier par Elibaal, roi de Byblos, Syria 6 (1925): 101–117

- Christopher Rollston, "The Dating of the Early Royal Byblian Phoenician Inscriptions: A Response to Benjamin Sass." MAARAV 15 (2008): 57–93.

- Benjamin Mazar, The Phoenician Inscriptions from Byblos and the Evolution of the Phoenician-Hebrew Alphabet, in The Early Biblical Period: Historical Studies (S. Ahituv and B. A. Levine, eds., Jerusalem: IES, 1986 [original publication: l946]): 231–247.

- William F. Albright, The Phoenician Inscriptions of the Tenth Century B.C. from Byblus, JAOS 67 (1947): 153–154.

- Vriezen, Theodoor Christiaan (1951). Palestine Inscriptions. Brill Archive. GGKEY:WGXUQKP9C87.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)